(Author’s Note: I have revised the system since original publication and edited this post to reflect that. I will note where below.)

Part 1: Introduction

This guest post is meant to build on two previous posts on this blog having to do with Diplomacy scoring systems. The first two posts form a point-counterpoint relating to two specific systems: Calhamer Points (sometimes known as “DSS”), and Sum-of-Squares. In this post I’ll assume you’re familiar with both systems.

This post is not meant to hold up one over the other, but instead to offer an alternative scoring system of my own design. In this post, I intend to explain why I think my system is good in theory. However, my system is so new that it has never been tested in practice—so if you think it sounds interesting, I would love volunteers for play-testing! Please message me on webDiplomacy or PlayDiplomacy (user jay65536)!

Before getting into my system, here is some background in case you are unfamiliar with the variety of scoring systems in use in tournament Diplomacy:

Scoring System Mechanisms

With the exception of some purely draw-based systems (such as the rating systems of PlayDip and webDip), all scoring systems currently in use are a combination of at least two of these three categories:

1. Draw-based scoring assigns points to each player based on how many players finish the game not having lost (so, absent a solo win, the number of players remaining in the draw).

2. Center-based scoring assigns points to each player based on how many centers that player finished the game with.

3. Lead-based scoring assigns points to each player based on the differences in centers between the players, sometimes including the difference in number of years played before elimination to differentiate losses. A subset of this is rank-based scoring, which assigns points based on the relative positions in the center counts (but not using the size of the center differences).

Calhamer Points would be an example of a purely draw-based system. Taking a fixed pot and dividing it equally among draw participants clearly uses no information other than whether the game ended in a solo, 2-way, 3-way, etc. This system is often just called “draw-size scoring”, although that is a misnomer; it is possible to have a purely draw-based system that differs from Calhamer Points by removing the requirement that it be fixed-sum. For example, a system that assigns 600 points split equally among participants in a draw, but 760 for a solo, is also draw-based (this was the primary system used in the Online Diplomacy Championship in 2017).

Most scoring systems in use today combine these aspects in a way such that one is the most important, and others are secondary or tertiary. This is true of almost all systems that primarily use lead-based scoring (these systems also use center counts as a secondary component). Examples include Carnage[1]Each game is worth 28,034 points. Anyone who solos gets it all. In a draw, players are ranked by center count (and then by most recent elimination). Top rank gets 7000 points, second 6000, all the way down to 1000 for seventh. Ties in rank get the average of the point values for the places … Continue reading, Super Pastis, and C-Diplo. Sum of Squares (which, again, I am assuming you are familiar with) is a hybrid system, combining lead-based and center-based elements in such a way that it’s impossible to call one the “primary” component.

Part 2: Why A New System?

I suppose any discussion advocating for a certain scoring system should start with the obvious question: “Why not Calhamer Points?”

Calhamer Points is the simplest and “purest” system in existence; it is (and mathematically must be) the only system that both treats Diplomacy as a fixed-sum game and adheres to the rulebook principle of equal draw sharing. So before talking about what I believe my system (or any other) does right, it is worth discussing what I believe almost all draw-based scoring systems (including Calhamer Points) do wrong.

In my opinion, there are two different aspects to what we look for in a scoring system:

- What are the “rewards” that the system is supposed to encourage the players to play for?

- Does the system do a good job in practice of rewarding what it is supposed to be rewarding?

BrotherBored has already written a long defense of Calhamer Points, in which he discusses some of what Calhamer Points is supposed to reward in theory. The main point he makes is that Calhamer Points is meant to reward small powers who cling to life and scrappily fight their way into the draw.

In CaptainMeme’s counterpoint defending SoS, he points out—correctly, in my opinion—that while Calhamer Points carries good incentives for small powers, it does not carry good incentives for large powers; there are many situations where, under Calhamer Points, it is debatable whether pushing for a win (as opposed to narrowing down the draw size) is a strategic mistake. (I’ll give an explicit example from my own experience below.)

The Practical Problem with Calhamer Points

In addition, there is a bigger issue based on the #2 aspect we look for in a scoring system: In my experience in high-level tournament play, Calhamer Points does NOT incentivize small powers to fight for their lives, as it is purported to do in theory. In fact, what Calhamer Points actually encourages is endgames where the 3 (or sometimes 2) biggest powers collude with each other to knock out everyone else, leaving small “Desperado” powers (to borrow terminology from BrotherBored) with no chance to actually make the draw. Then they take their 3-way (or 2-way) draw and the resulting higher score than a 4-way or 5-way. I have seen this so much in high-level games played with draw-based scoring, I would argue that virtually all of the time a “Desperado” does make it into the draw, it happens as a result of (a) one or more of the 3 largest powers not being good enough at draw-whittling, or (b) one or more of the 3 largest powers playing “against the system” and taking a draw not caring about the smaller point value.

The point is, in practice, the theoretical incentive for small powers to sneak into a draw is overpowered by the practical fact that the larger powers (unless they have not given up on soloing) have a common incentive to knock them out. Since the ability to obtain a good score without approaching a solo win is usually the only theoretical benefit of Calhamer Points that its supporters tout, this seems to me like a very big problem. Also, I think it is important to note that draw-based scoring is the only scoring mechanism where the top powers can have an incentive to collaborate instead of compete.

Example: Online Diplomacy Championship 2017

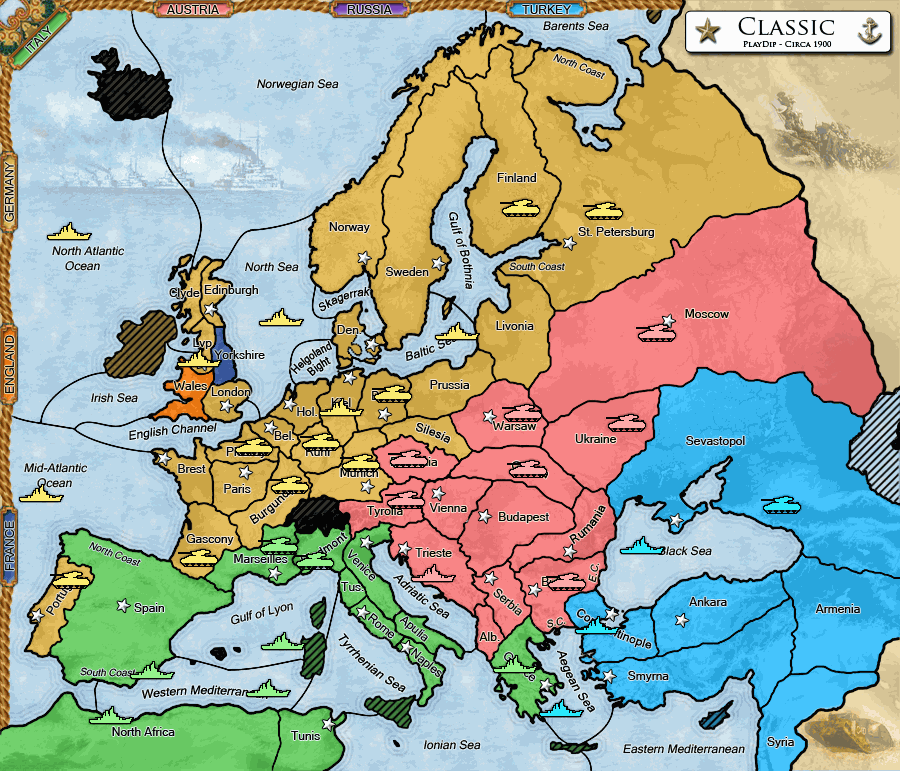

Now, to segue into “why my system,” let me give an example from the last tournament I played in that used a draw-based system (Online Diplomacy Championship 2017, in case you’re curious). The end result of the game was a 4-way draw; the center counts were G15 / A8 / I7 / T4.

Final Board, Spring 1909

So this is an example of two fairly common scenarios in a Diplomacy endgame: one large power pushing for a solo but getting stalemated, and one small power sneaking into the draw. (Full disclosure: I was Turkey.) This game, to me at least, can serve as an example that validates the detractors of both Calhamer Points and Sum of Squares—but in different ways. (It’s only one example, but it’s meant as a segue point, not a proof.)

To see the problems with Calhamer Points, let’s rewind back to the decision point where Germany actually started the solo push. He had been working well with both Italy and Austria as part of a Central Triple; all 4 other powers were on their last legs. It would have been quite easy for Germany to play passively, take his time mopping up England and France, and allow Italy and Austria to focus on taking out Turkey. Instead, he decided to make a run for the stalemate line, figuring (correctly) that the English and French centers he’d need to get the solo would still be easy to take later. As soon as his allies saw what he was doing, they made their own run to the stalemate line and successfully held one. But the resulting position was one where none of the bottom 3 powers felt comfortable turning on another.

So the salient question from a draw-based perspective is, was Germany’s solo push a mistake? There’s easily an argument that it was. By making the decision to try to win, Germany effectively lost points relative to a guaranteed 3-way draw that he would have obtained by playing passively. Many proponents of draw-based scoring would argue that there is nothing wrong with this, but I disagree; I don’t believe a scoring system should ever punish someone for trying to win and only failing due to stalemate (as opposed to failing because you get outplayed and go backwards).

Lead-based (and center-based) scoring systems never have this problem: if you top your board, you always get a high score, and therefore, a player in the German’s position would be rewarded for outplaying his competition (although the reward would not be as high as if his solo bid succeeded).

The Practical Problem with Sum of Squares

These other systems have a different problem. For example, what if my ODC 2017 game were scored with Sum of Squares? The sum of squares of the center counts is 225 + 64 + 49 + 16 = 354, so the scores would be G 63.56 / A 18.08 / I 13.84 / T 4.52.

Sum of Squares is meant to ensure that Germany is rewarded far above the other players for being the only one who is anywhere near a win, and at that it succeeds. But in this example, the score for Turkey is so minute as to be basically negligible, which would drastically decrease Turkey’s motivation to stop Germany’s solo.

In fact, I know that in the Online Diplomacy Championship 2019 (which was scored with Sum of Squares) some early-round games ended with small powers throwing solos solely to keep their scores the same as all but one player. The tournament structure rewarded finishing the first 2 matches anywhere in the top 28, so keeping most (but not all) players at a score that would be easier to pass in the other match was viewed (by these suicidal players) as advantageous. In his defense of Calhamer Points, BrotherBored referred to this as “nihilism,” which I’d say sums it up fairly well. Small powers’ scores are so scant as to often take away the motivation to compete.

In my opinion, Sum of Squares also has another problem, and—believe it or not—it concerns the reward for the top scorers. While I think that in my ODC 2017 example, the German player should have a significantly higher score than any other player, I do not believe that the reward for any draw should be such a large percentage of what a solo win is worth. In Sum-of-Squares, two high-scoring draws (50+) can surpass a solo (100) and a loss (0). Soloing is hard enough that it should be harder to surpass a solo than with just two strong draws!

I might also raise another point (one that I expect would appeal to defenders of draw-based scoring) about this example. I’m not assuming you’re familiar with any rank-based systems, but almost all of them would create a scoring gap between the Austrian player, who is second with 8 centers, and the Italian, who is third with 7. If you are used to playing under Calhamer Points, this must strike you as very odd. Even if you think there is a difference between finishing with 8 versus 7 centers (and I’m sure many Calhamer Points players would say there isn’t), you could still believe that this difference should be slight, especially in light of the fact that their endgame positions are basically the same (they are both stopping a much larger power from soloing). This sort of example doesn’t really make me personally opposed to rank-based systems (I think this is an “edge case” not much worth getting upset over), but it is still worth thinking about, especially because I’m about to compare with what my new system does.

Part 3: What is “Two-Tier Scoring?”

My new system is meant to be a hybrid of all three of the components I described in the introduction (draw-based, center-based, and lead-based). Before getting into the details, let me share one observation about a stark contrast between Calhamer Points and Sum of Squares. In Calhamer Points, if you lose the game you get 0 points, and otherwise there is exactly one score that is assigned to all players: the pot size divided by the number of people splitting it. In Sum of Squares, if you lose the game you get 0 points, and otherwise, barring a tie in center count, all players receive different scores. In fact, it is almost universal among non-pure-draw-based scoring systems to give each player an individual score.

My system splits the difference: in the event of a draw, sometimes the draw is equally shared, but in most cases there will be exactly two different scores given out: one “top” score for the top performers (according to the system) and one “bottom” score for the other draw participants. This is where I got the name from.

Now let me show the actual scoring math:

(1) Each game is worth a fixed number of points—let’s use 180 to make the numbers look good. If you lose (by elimination or otherwise), you get 0.

(2) (a) In a solo win, the winning player receives 180 points.

(b) In a 2-way draw, each participant receives 90 points (and for tiebreaking[2]The tiebreakers were omitted from the original article. They’re now included. purposes, each of their center counts is understood to be 17[3]This parenthetical is only necessary when playing in a game where draws not including all survivors are allowed. My system takes these kinds of games into account.).

(c) In a 3-way draw in which no one has more than 12 centers, each participant receives 60 points.

(3) In all other draws, we first determine how many players qualify for the “top tier” of scoring. Any player who possesses the highest center count or is within 1 center of the highest center count is considered qualified. Scoring then works as follows[4](3) is a revision of the original article, but not the system itself. It’s just an attempt to better explain what the system really does.:

(a) If only one player qualifies for the top tier, that player receives the “top score”, which is a function of that player’s center count (see below). All other draw participants equally split the remaining points (out of 180).

(b) If more than one player qualifies for the top tier, each draw participant not qualified for the top tier receives the same score they would have received in (a). The qualified players then equally split the remaining points (out of 180).

(4) The top scores for each center count are as follows:

7 or fewer: 54[5]This is the first actual revision. The old rule covering draws where no one had reached 7 centers was a needless exception that has been done away with.8 or 9: 57

10 or 11: 60

12: 63[6]This is the second–and biggest–revision. The top score for 12 centers used to be 60. Now it is 63, BUT the rule about 3-way draws being equally shared if no one has more than 12 still applies. This means that if you are topping your board and you have exactly 12 centers (and lead by … Continue reading13: 66

14: 72

15: 78

16: 84

17: 90

(5) In the case of players having the same point total, the following criteria (in order) are used to break ties:

1. Most solo wins

2. Most draws finishing alone in the top tier

3. Most draws finishing alone with the highest center count [Note: this tiebreaker, and ONLY this tiebreaker, counts board tops in equally shared 3way draws, as well as 1-center leads.]

4. Highest-scoring single result, down the list if necessary [Note: for any of the tiebreakers below this one to apply, the players must have all the exact same round scores when arranged from highest to lowest.]

5. Largest center lead in a draw finishing alone in the top tier, down the list if necessary

6. Most total centers across all draws

Any players not separated by any of these 6 tiebreakers are considered to be genuinely tied.

I hope I didn’t make the math seem too hard, because it’s actually pretty easy to do in practice! Let me show you some examples of how it would work.

Example 1: In a 14/10/10 3-way draw, the 14-center power would be awarded the top score, which is 72, and the 10-center powers would split the remaining 108, for 54 points each. Notice that the center counts of the smaller powers don’t matter, and hence the scores are unaffected, as long as the 14-center power leads by more than 1 center (and as long as the 14-center power stays on 14).

Example 2: In a 15/14/5 3-way draw, we would start with the computation in (3)(a): the top score is 78, and the “bottom score” is 102/2 = 51. That means the 5-center power gets 51 points, but because the other two powers are within 1 center of each other, they each get (78+51)/2 = 64.5 points.

Example 3: In an 11/9/8/6 4-way draw, the 11-center power gets the top score of 60, but now the three other draw participants split 120 points, for a total of 40 points each. Notice that while the top score matches the score for an equally shared 3-way, this 60-point result counts towards the second tiebreak, while an equally shared 3-way counts towards the third tiebreak at best.

Example 4: In an 11/11/6/6 4-way draw, the top score is again 60, the bottom score is again 40, but this time there are two board-toppers. So the scores break down 50/50/40/40. Unlike in the previous example, joint board tops do not count towards the second or third tiebreaks.

Example 5: In an 8/8/7/6/5 5-way draw, the top score is 57, and the bottom score is 123/4 = 30.75. The top 3 players will equally split 57 + 30.75 + 30.75 = 118.5, so the scores break down 39.5 for each of the three players and 30.75 for each of the bottom two players.

Part 4: Why Use the Two-Tier Scoring System?

Let me just say, before I begin, that what follows is my totally theoretical opinion about the merits of my system. As I said above, it has never been play-tested. Plus, I’m obviously biased. Perhaps there would be some issue I haven’t foreseen. Nevertheless, here’s my opinion of what my system does well:

1) Rewards for Strong Draws

Two-Tier Scoring preserves the idea that animates all scoring: that good draw performances should have a good result. As a hybrid of draw- and lead-based scoring, my system gives multiple ways to attain that reward. If you follow a strategy of playing to knock out your opponents, and you execute it well, you can get a good score: a 2-way is 90 points, an equally shared 3-way is worth 60 points, and most 3-way draws, even if not equally shared, are worth 50+ points. (For comparison, an equally shared 4-way is 45, which is also the absolute minimum a 3-way can be worth in my system.) If you follow a strategy of racking up centers and keeping your opponents below you in the center count, and you execute it well, you can get a good score as well: the top score for any board leader with 10 or more centers is at least 60 points, and the top score for a 17-center power (barring a different 16-center power) is 90, which is equal to a 2-way.

But in order to break the 60-point barrier, you have to top (or co-top) your board with 12 or more centers. The idea (though there will be edge cases, as with any system) is that to get the very best non-solo results, you have to put yourself in a position where at least you are threatening to solo.

2) No Penalty for Selfish Play

Two-Tier Scoring preserves the idea from non-draw-based scoring that pushing for a solo and getting stalemated never hurts your score. The top score for any sole board leader is fixed and does not depend on draw size. More generally, if you are set to earn the top score, my system ensures that that top score is the highest score it is possible to attain without gaining centers. In other words, helping someone else take centers, or handing them to someone else, so that you can draw-whittle, will never increase your score above the top score for your center count, though in some cases it won’t decrease it either. This actually explains why the top scores for 7-11 centers are what they are—they were calculated to make this true. As I said above, the system is meant to be flexible with regards to player strategy.

(While I’m on this subject, the top score for 17 centers is 90 for exactly the same reason as above, and the top scores for 13-16 centers are what they are simply to make each center between 13 and 17 worth the same amount of points.)

3) Rewards for Small Powers

Two-Tier Scoring preserves the idea from draw-based scoring that small powers who stay alive to make it into the draw deserve a significant enough reward for their effort. It just bends the idea that the reward must be an equal score for everyone. Instead, it makes the scores equal for all but the single biggest power. To go back to the example above, with the 15/8/7/4 endgame, the German player would receive 78 points under my system and the others would receive 34 each. 34 points out of 180 is very close to being what an equally shared 5-way draw would be worth (36). So the 4-center Turkey receives almost as good a score as he would under Calhamer points if he had snuck into a 5-way instead of a 4-way. This doesn’t seem too objectionable to me!

4) Fairness

Draw-based scoring uses the idea that once a draw is called, your center count does not matter, and neither does your center rank. My system preserves this idea as much as possible while also maintaining point (2). Taking the above example again, Calhamer points would say, “All 4 of you took a draw, so you all get equal credit.” My system bends this as little as possible: the German player is near a solo and gets credit for being a 15-center solo threat, regardless of draw size, and the other 3 powers stopped the solo and get equal credit (to each other, but not to the solo threat) for their part in that. Two-Tier Scoring makes a distinction between not winning because you are the dominant power but couldn’t make it to 18, and not winning because someone else is closer to 18 than you are. But unlike any other non-draw-based system, it makes no other distinction.

5) Different Incentives for Different Sizes

Two-Tier Scoring avoids one of the major pitfalls of draw-based scoring: all of the largest powers having a common endgame incentive not to compete with each other. But it does this in a unique way. Rank-based systems avoid this pitfall by giving the largest powers a common endgame incentive to compete with each other (the top rank)—but if one power pulls far enough ahead, the competition could be over. (Whether this is good or bad is debatable, and I don’t intend to get into that here.)

My system attempts to create different endgame incentives for different players. For example, in a game with several powers near the top center count, a competition for the top rank might ensue, similar to what would happen in a rank-based game. But if there is one clear leader, instead of settling into a quick draw, the other powers—but not the leader—might have an incentive to draw-whittle! This is distinct from draw-based scoring because, under Two-Tier Scoring, a sole board leader doesn’t care about the draw size at all. That could allow the board leader to interfere with any draw-whittling without hurting their own score, perhaps making alliances with the small powers. It could also potentially mean that the board leader might help whittle the draw down only in exchange for more centers, possibly getting close enough to a solo that the other draw-whittling players are playing with fire.

Exactly what kinds of endgames we would see, and whether it makes endgames more fun, is a big unknown that I hope play-testing can shed light on.

6) One Solo Always Beats Two Draws

Two-Tier Scoring avoids a pitfall of some other systems (believe it or not, this is not confined to a single category of system): a solo being too easy to catch via multiple non-solo results. In Calhamer points, you always need at least 3 draws to pass a solo. In my system, because a draw is never worth more than half of the points that a solo is worth, and because the first tiebreak is “most solos,” it is impossible for a solo to be caught by only 2 draws. (Of course, we could have the same first tiebreak for Calhamer points, and the same conclusion would apply.)

Some people would argue—and I am somewhat sympathetic to this argument—that a solo should be even harder to catch than that. But mathematically, if you want to make a solo impossible to catch by any 3 draws, you have to either use a non-fixed-sum system or start differentiating between (and thus giving credit to) losses. I personally think keeping the math almost the same as in Calhamer points is preferable to either of these (especially giving points to losses).

Part 5: Why Not use Two-Tier Scoring?

Well, again, it’s never been tested, so it’s hard to say! That is why I want to end as I began, by saying that I hope this idea interests enough people that they’d be willing to try playing under the system and seeing how it compares to the others that are out there.

If you are interested to play, please message me on webDiplomacy or PlayDiplomacy (user jay65536)!

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Each game is worth 28,034 points. Anyone who solos gets it all. In a draw, players are ranked by center count (and then by most recent elimination). Top rank gets 7000 points, second 6000, all the way down to 1000 for seventh. Ties in rank get the average of the point values for the places the tie takes up. Then everyone gets 1 point per center. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The tiebreakers were omitted from the original article. They’re now included. |

| ↑3 | This parenthetical is only necessary when playing in a game where draws not including all survivors are allowed. My system takes these kinds of games into account. |

| ↑4 | (3) is a revision of the original article, but not the system itself. It’s just an attempt to better explain what the system really does. |

| ↑5 | This is the first actual revision. The old rule covering draws where no one had reached 7 centers was a needless exception that has been done away with. |

| ↑6 | This is the second–and biggest–revision. The top score for 12 centers used to be 60. Now it is 63, BUT the rule about 3-way draws being equally shared if no one has more than 12 still applies. This means that if you are topping your board and you have exactly 12 centers (and lead by more than 1), you’d actively prefer a larger-than-3-way draw, which is worth 63, over a 3-way, which is worth 60. This is the only time draw size matters to a player who is alone in the top tier. I consider this flaw to be much less bad than the flaw that it fixes, which was that finishing on 12 centers in a 13/12/9 3-way, which is worth 61.5 points and is not even a board top, let alone a sole-top-tier finish, was the most you could get for finishing on 12. Now the most you can get is by finishing alone in the top tier and earning 63, with draw size mostly irrelevant. |

This system does address some of the issues raised, but has serious problems with endgame. Think about the common scenario of a big power stopped short of a solo by an alliance of 3-4 smaller powers.

The common theme of how the endgame works (and a necessary and valued theme of the game) is that these powers jockey for key centers in the draw line, and negotiate with the large power for space to whittle the draw size.

In this scoring system, the large power has NO reason to allow this. In fact, they are incentivized not to (so that the opponents all have smaller scores). The common way this happens is when a power is convinced they cannot solo, they hand over 1 or 2 key centers to allow security for draw size whittling to occur (and sometimes clever and nefarious backstabs occur all around).

Here, the large power is penalized for doing this, not just by their personal score, but in tournament setting they WANT a large draw so that everyone else gets fewer points.

The scoring system that addresses all these problems was used on Diplomacy.ca The mathematical hurdle you have to surrender is “Scores in games don’t always sum to the same amount”. Give that assumed condition up, and coming up with a good system is MUCH easier.

I don’t quite see why it is a necessary and valued theme of the game that the lesser powers be allowed to do that. It seems quite unrealistic to me that a dominant empire would encourage the rest of the continent to consolidate. A “divide et impera” attitude seems to me a lot more appropriate.

That said, I am still quite new to the game so perhaps there is something I’m missing. My own bias is also towards seeing the game as more of a “simulation” (however imperfect it may be) rather than a game with arbitrary rules that uses the setting just to add a bit of flavor.

I really like the core idea of this scoring system; it incentivises large powers to get close to a solo and small powers to survive.

The system is very complicated, with three exception cases and lots of parameters. I do wonder if there is a much simpler system which is nearly as good. One attempt inspired by your system would be: the board leaders (or those within one SC) get SCs/34 points; everyone else splits points equally.

One strange incentive I can see appearing is when there are two powers with many centres. Then the remaining powers have a large incentive to make one of them a clear leader. E.g. 17/15/2 draw is much better than a 15/15/4 draw for the smallest power.

I think it is good that people are thinking about scoring systems. My first impression is that the system you have proposed is an improvement on a purer draw based system, but will still suffer from issues that draw-based scoring suffers from (e.g. artificial draw-whittling).

I see you compare it to sum of squares. Sum of squares has been known to be bad for about 20 years now and I don’t know why it is popular. I feel as though I should’ve spoken up against it when it first made a resurgance in Chicago a decade ago.

The known fix for sum of squares to make it a better system is to use a different function than f(n)=n^2 to score the players in a draw. ManorCon uses f(n)=n^2+4n+16 and works better than every system mentioned in this article. I am partial to using f(n)=sqrt(n^2+6n+10) which has never been tried in a tournament but is deliberately constructed to closely match the cricket scoring system.

Oh wow, are you the Australian mathematician Peter McNamara? If so, hi! (We’ve met/played before, though we haven’t seen each other since 2013 in San Diego.)

I definitely appreciate your comment; as someone who’s never played outside North America, I was unaware of the variety of systems that Australia has. In North America, as you probably know, the only 3 systems in wide use in FtF are Dixiecon, SoS, and Carnage, and in the online community it seems like everyone uses pure draw-based scoring. I’ve also never played under the ManorCon system and so I don’t know what it’s supposed to do right that corrects the problems with SoS.

I’m curious about your proposed f(n) = sqrt((n+3)^2 + 1). Do you have a specific reason why you couldn’t just use f(n) = n+3 to make the scoring simpler? It also seems to me like using a linear function with a constant term, or even one that is close to linear, might re-introduce draw-whittling due to the fact that the denominator of a player’s score is going to depend more heavily on the number of survivors (with f(n) = n+3 it would be 34 plus 3 times the number of survivors) than if the function is quadratic. (I looked up the cricket system and it seems that that system gives points to survivors in a non-zero-sum fashion.) Also, just for my edification, are the systems you’re talking about designed to be played in timed games only (as in, ending in a particular year), or are they also meant for untimed games?

But this is all theoretical. My goal in writing the article was to try to attract play-testing volunteers.

I think I like the general principle of the scoring system. It seems quite complex and that is what will most likely turn people off. But it’s only complex if you want to know the exact score. And how many players can tell what their exact score will be in a SoS game? Most just follow the principles that more centers is better and that the more divided the rest of the board is the better.

For a qualitative analysis of the situation on the board using the two tier scoring system it is enough to know that outside of special cases there will be two tiers of scores, everyone in a given tier is ranked equally, and the way to get in the top tier is to be within 1 center of the center count leader. And that is plenty to play the game and formulate your strategy.

As such my main criticism would be not for the system itself, but rather for the article’s composition. It would’ve been more effective to lay out these principles first instead of intimidating casual readers with the detailed explanation of how exactly score is calculated.

This is absolutely a valid criticism that I’ve heard elsewhere. In most cases, the scoring is much simpler than the formulation here. It just says:

The board leader earns the top score, and all other survivors split the remaining points.

The only two exceptions to this are (1) ties for board lead (which includes someone being within 1 center of the lead), and (2) some draws in which not all survivors are included. Those cases are still covered by the rules in the article.