Please note: After I published this article, I received an unusually large amount of commentary and feedback. In response to requests for me to clarify and elaborate upon some of my points, I revised this article on 9/25/2019.

While writing my article “3 Reasons Why Luck Plays No Part in Diplomacy”, I pondered:

Why do so many players deploy the word “luck” to describe Diplomacy’s gameplay?

I stand by my statement that luck plays no role in Diplomacy. But I must acknowledge that there is something going on with Diplomacy that motivates players to use the word “luck” to describe what they experience.

Since Diplomacy doesn’t involve randomized gameplay (other than the assignment of the powers at the start), what phenomena are the players referring to when they say that “luck” happens during a match?

1. Diplomacy is a Free-For-All Game

Free-for-all gameplay is notoriously frustrating.

In a typical one-on-one game, all the pieces (or their equivalent) are either under your control or your opponent’s. The situation is basically the same in any team game with two teams; each player is either friendly (a teammate) or hostile (an opponent). When your opponent’s pieces or the opposing team spoils your plans, you’re not especially disappointed; that’s the point of the game.

Free-for-all rules muddy the distinction between “friendly” and “hostile” players. In free-for-all games, you get into situations where you wish you could control another player’s pieces as though those pieces were your own. You want a rival player to behave like your teammate, but they refuse. These experiences are uniquely disappointing; you should expect an opponent to oppose you, but a rival in a free-for-all game might have (or even should have, for their own sake) acted as you desired.

It is popular to play the various Super Smash Bros. games on free-for-all mode. But it sure is frustrating when one guy hides in the back and waits for everyone else to take each other out.

Furthermore, some games with free-for-all gameplay have a problem that I’ll call free-for-all syndrome. Tournament Poker suffers from free-for-all syndrome. A weak player may “feed”[1]”Feeding” is a term I learned playing video games, and I don’t know another word for this concept. chips to a strong player, who then has a huge advantage. A stronger player who has been fed typically takes the lead and never loses that lead. This is especially common in Tournament Poker because a player with a lot of chips can use that lead to push other players out of playing risky hands.

I’ve played tournament-style poker with groups of mixed skill, and it’s miserable. Often, an inexperienced player gets bored and starts making huge bets for no tactical benefit. This makes them a “feeder.” Whichever other player happens to have a strong hand when this happens gains a huge chip lead.

In my experience, playing Tournament Poker with a mix of strong, moderate, and weak players is much less fun than playing with players of matched skill. Diplomacy also has this “feeder” problem, which leads to my next observation:

2. Diplomacy Has Snowballing

In the context of games, “snowballing” is a metaphor that refers to how a large-enough ball of snow can start rolling downhill on its own momentum, gathering more snow onto itself as it rolls.

Snowballing means that a player’s early successes make future successes easier to achieve. In Diplomacy, capturing a supply center from another player nets you a point, but it also nets you a new unit. Your new unit makes it easier for you to gain more points (and more units) on future turns.

Snowballing an unusual game mechanic. In most games (and virtually all sports), scoring points does not result in your gaining advantages that make it easier to score more points. (E.g., in basketball, your team size does not increase if you score points.)

Because Diplomacy features snowballing, the first few turns often determine the overall momentum of the match. Snowballing also greatly amplifies the free-for-all syndrome, because one strong player can attain a great deal of power by predating upon a weaker neighbor.

3. Online Diplomacy Matches Last Forever

Online Diplomacy matches may take months to finish, and real life gets in the way. Players’ performances may suddenly drop in quality, or players may drop out of a match altogether. This problem exists in any game (e.g., someone may get bored and distracted, or need to quit) but is particularly noticeable in drawn-out matches of Diplomacy. I am not aware of any other board game with daily turns and months-long matches.

Keeping one’s allies interested and involved in a match—especially in long, grinding games—is challenging, even maddening, since there is only so much one can do to affect another player.

And finally:

4. Diplomacy is a Guessing Game

Diplomacy requires the players to choose their moves simultaneously. This fills every turn with the anxiety of not knowing what the results of your choices will actually be.[2]A reminder, dear reader: uncertainty in what your rivals will do does not constitute luck. As I wrote in the companion piece, anticipating opponents’ choices is a skill.

Why the word “luck?”

So I listed some frustrating aspects of Diplomacy. I have experienced these frustrations myself. But what is it about these problems that compels players to disagree with the statement “Luck plays no part in Diplomacy?”

Why do players (myself included!) fixate on the word “luck?”

1. They Don’t Necessarily Know

When directly asked, your typical luck-camp person will answer this question with something like “I said what I said because I think it’s true.” This answer intrigues me because this answer is almost a tautology. There is a more meaningful answer, but the answerer is either unwilling or unable to elaborate. Most people I know are unable to meaningfully answer questions like this about themselves because they really don’t know why they think what they think. Probing questions about their epistemology or motivations are so uncommon that they don’t know how to handle the situation. They may even take offense to such questioning.

I am genuinely interested in examining the hidden thoughts and motivations that cause someone to believe that the word “luck” is appropriate to describe Diplomacy’s gameplay. However, I don’t exactly trust the people making the assertion to tell me what they’re really thinking. Generally speaking, the average person cannot reliably explain their own thoughts, feelings, and ideas. “Know thyself” is an adage because most people don’t know themselves.[3]I have written much more on the art of speculating about others’ hidden thoughts. Click here to read one of my philosophical essays on the subject.

2. Because Everything

Many game players (myself included!) are strongly opinionated about the concept of luck and its role in games. This is a meaningful difference in perspective. Although the question “what is luck?” sounds so trivial at first, I believe that what a person deems to be “luck” in a game reflects the way that person views on life in general. Let me explain.

Many games are simple and can be mastered easily, such that there is little to distinguish a genius player from a merely experienced player (e.g., The Settlers of Catan). This phenomenon is often described as the game having a “low skill cap.” At some easy-to-reach level of mastery, it is not possible to improve further at the game.

In deep or elaborate games—games that might be described as having a “high skill cap”—there will be some idea that is so complicated, some information that is so difficult to ascertain, some tactic that is so challenging to master, etc., that a human being cannot reach the theoretical skill limits to the game. Diplomacy is such a game because Diplomacy involves many skills that a human being can never fully master (for example, manipulating other people who anticipate that you are trying to manipulate them.)

When playing a high skill cap game, a player cannot depend solely on memorization, pattern-recognition, statistics, and so forth. By definition, the player cannot master everything about the game. And during actual matches, there are limits on a player’s time and mental energy. With regard to the toughest decisions, the player will eventually come to depend on their philosophy of life, their outlook towards the world in general.

“The Culture – a humanoid/machine symbiotic society – has thrown up many great Game Players. One of the best is Jernau Morat Gurgeh, Player of Games, master of every board, computer and strategy. Bored with success, Gurgeh travels to the Empire of Azad, cruel & incredibly wealthy, to try their fabulous game, a game so complex, so like life itself, that the winner becomes emperor. Mocked, blackmailed, almost murdered, Gurgeh accepts the game and with it the challenge of his life, and very possibly his death.”

If my statements about the connection between one’s personal philosophy and one’s approach to games intrigues you, let me recommend the 1988 Science Fiction novel “The Player of Games,” by Ian M. Banks.

A player’s life philosophy will be reflected not only in how they play through a given match of a particular game, but also how they think about games in general, whether and why they play the games, and how they think and feel about the past matches they’ve played. Diplomacy is one of the deepest games. When you sit down to play, you bring your very understanding of human nature to the table.

So when Player X describes the amount of luck in a game, there’s a good chance that Player X is telling you not about that game, but about Player X’s outlook on life. That’s right: I’m saying that many players unconsciously use the word “luck” to describe how they feel about a game, rather than to describe the game itself.

3. Luck is a Loaded Word

Loaded words and phrases have significant emotional implications and involve strongly positive or negative reactions beyond their literal meaning. For example, the phrase tax relief refers literally to changes that reduce the amount of tax citizens must pay. However, use of the emotive word relief implies that taxation is an inherently unreasonable burden.

–Wikipedia

If we describe Diplomacy’s rules in precise, technical language, there’s nothing to argue about:

- “The rules of Diplomacy do not require players to use randomized information (other than the selection of powers at the start).”

- “Diplomacy is a game of imperfect information because players choose their moves simultaneously.”

- “Each Diplomacy player has the ability to choose their moves independently, that is to say, they may disregard what any other player says or does.”

See what I’m saying? It’s the word luck that drives the conversation.

Luck is a special word. Luck is a magic word. Luck is a loaded word.

Luck is a loaded word like justice, fairness, love, or hate. Loaded words are not “just” words; these words correspond to concepts.[4]The philosophical study of how words correspond to concepts is called Semantics. And the concepts of justice and love are some of the most important concepts people come to understand. People will kill and die for justice and love. You could parse the universe atom by atom and would never find one atom of justice or love… but for many people, these concepts are more important and more real than any material object.

Like justice, love, fairness, and a host of other words I could come up with, luck has a certain subjective meaning because luck—unlike “randomized information” and “imperfect information”—luck is also a feeling.

If this is a conversation about mere word choice, why do so many players seem to care?[5]Edit: My support for the Avalon Hill statement definitely riles up certain people; I have received a disproportionate number of messages about this piece, and my writing spawned huge conversations on other websites. It’s because they’re hung up on the word luck. They can’t let it go. They’re compelled to disagree, because their fundamental beliefs about the world and how they relate to it are infringed on when I shock them with my counter-factual statement[6]Counter-factual in their view, not mine. that their inability to out-guess another player does not count as luck.

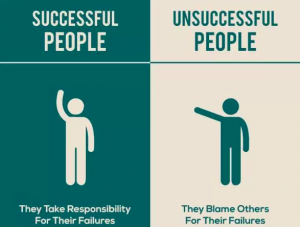

My point is very abstract, and I think I’m reaching the upper limits of my abilities as a communicator, but this is the crux of what I’m saying: your desire to call something “luck” reflects a fundamental belief or feeling that you have, and this feeling comes from your desire to accept (or reject) responsibility for the outcome.

Recall my list of four Diplomacy difficulties that players commonly call “luck:” Free-for-all Syndrome, Snowballing, Draw-out Matches, and Simultaneous Guessing. All four difficulties have something in common—each makes the player feel like they are not in control of the outcome of the game.

4. The Ego Problem

What did Obi-Wan mean when he said “In my experience, there’s no such thing as luck”?

In “Star Wars” (1977), the character Obi-Wan Kenobi trains the hero Luke Skywalker to block a robot’s laser blasts using his handy laser sword—but without using his sight. Luke eventually succeeds. Observing, the egotistical Han Solo describes Luke’s feat as “luck.” Han’s intention is to diminish Luke’s accomplishment by implying that Luke doesn’t deserve credit for what he did, or that Luke couldn’t repeat the feat in the future. Something like that.

Obi-Wan, certain that Han Solo is wrong, defends the accomplishment of his pupil by stating that there is no such thing as luck at all. What an interesting exchange!

Although I do think that there is “such a thing” as luck, I believe I can learn a lot about another person from whether they appropriately distinguish between situations involving “luck” and those that do not.

In the fictional anecdote, Han’s ego is so out of control that he has ascribed “luck” to a situation where luck plays no role. He thinks too highly of himself, and to protect this fragile opinion, he has to lie to himself about the meaning of Luke’s accomplishment. Han is self-deluded. Han is not just delusional about what he saw Luke do; Han is delusional about life in general and his relationship to the world.

Similarly, I meet people all the time who are deluded by their egotistical feelings. Somehow, the accomplishments of others make them feel bad. Maybe they’re jealous. Maybe they’re insulted. The precise feeling doesn’t matter as much as the ultimate conclusion: others’ achievements are “luck.”

This kind of delusional thinking is easily compounded in the setting of a competitive game, where others’ victories are juxtaposed with one’s own defeats. The thought process goes something like this:

- I am great at games, so as long as I avoid bad luck, I will usually win.

- I didn’t win.

- Therefore, I was unlucky.

The unconscious goal of this sort of thinking is to absolve yourself of responsibility for your own limitations.

Conversely, if your ego inappropriately attributes your success to “skill” (in my companion piece, I described “skill” in contradistinction to “luck”) when you just blundered or lucked your way to victory, that’s also a delusion. When the other player wins, that’s luck; when you win, that’s your skill.

Players want to blame bad luck when they lose, but when they win they want to attribute their victory to their skill. Game players are like this because, well, the majority of people in general act this way; when they get a raise, it’s because they deserved and earned it; when they lose their job, it’s because of X, Y, and Z beyond their control.

Some games are mostly luck, and some games are mostly skill. To understand the truth—the true extent that you control your own destiny in a given game—will help you immensely as a player. My other post outlined my semantic argument about why Diplomacy involves zero luck, but what I’m yet even more interested in discussing is…

Which worldview leads you to be a better Diplomacy player?

I’m not going to hold back: I consider the over-broad understanding of luck[7]Describing everything you feel is beyond your control as “luck.” to be a self-imposed mental handicap. I think that feeling or deciding that something is “luck” is not just a mere choice of words; it is an application of a concept (“I am not in control”) to a particular situation.

If my blog has a theme, the theme is self improvement in general and getting better at Diplomacy in particular. So let’s set aside the question of “What is Luck?” and instead ask what perspective on the role of luck is more helpful to you as a competitor?

Here we go:

The more you believe that Diplomacy is about “luck” (in the sense sense of disavowing your own control or influence of the events that unfold in the game), the more you will approach your matches with a nihilistic (nothing you do matters) and defeatist (accepting defeat without a struggle) attitude. Reject this approach!

The more you believe that you control your own destiny, the more you will approach Diplomacy with with the diligent, creative, opportunistic attitude that is the hallmark of the best Diplomacy players. Take this approach instead!

A belief that you are “unlucky” will make you feel better, but a belief that you controlled your destiny will make you be better.

How do you control your own destiny?

1. Control Yourself

”Here is the great insight of the ancient philosophy of Stoicism: Shaping your character is ultimately the only thing under your control. So in order to exploit your good luck and cope with the bad luck, it is necessary to be a good person. Through a combination of rational introspection and repeated practice, you can mold your character over the long term.

Betting on your own improvement is a guaranteed win with the biggest payoff.”

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Rediscover the Ancient Philosophy of Stoicism

I could not say it better myself!

2. Take Responsibility For Your Misfortune

Every time something goes wrong in your Diplomacy matches (and I mean every time!), you should think about your responsibility for the problem. What could you have done to change the situation? What guesses would have changed the result? Who did you need to persuade to change the outcome? Always assess the match in terms of what you could have done, not what others did (and definitely not what the universe did).

In my two lengthy journals—one about a gunboat match and one about a press match—I examined my matches in painstaking detail. At no point did I ever attribute anything that transpired to “luck.” In both games, I got awfully close to a solo win, but was unable to get over the threshold of 18. That is the result of my own limitations—not the universe conspiring against me.

At the beginning of this post, I listed the endemic problem of players losing interest in long online Diplomacy matches, even sometimes quitting altogether. That’s a problem outside of your control, right? Wrong. There are many ways you can take control of the situation. For example:

- You can (and should!) assess your rivals at the start of the match as to whether they will be reliable and interested for the duration of the match. Use their attentiveness (or inattentiveness!) to your advantage. When alliance play is important, choose allies who are taking the match seriously. When you want an ally who you can later betray, consider alliance with an inattentive player who will give up when you backstab.

- If you need a player to stay involved, keep that player interested in the match. Think of something—anything—that will keep their attention. Use your powers of charisma, leadership, and persuasion to instill in them some motivation. Befriend them! This is an important skill for life in general, and anyone can learn to do it. People from all walks of life do this every day with their family, at their jobs, and so on.

3. Always Look for a Way Forward

Maybe there is such a thing as an un-winnable scenario, one where all your neighbors conspire against you and their decision to do this is adamantine and unbreakable. You get attacked, and nothing you could possibly have said would have deterred them, and none of your moves would have caused them to reconsider. Maybe.

But I refuse to think like this, and you should also refuse.

Is there really no timeline out there in the multiverse where you might prevail? Like if you got into that situation 14,000,000 times, you’d lose all 14,000,000 of them?

Or like Dr. Strange meditating with the Time Stone, is it possible for you to perceive at least one timeline out of 14,000,000 where you are able to pull victory from the jaws of defeat?

There is always a possibility of winning. There’s always hope. If you simply assume that there is something you can do to alter the outcome of the match (and you just have to struggle to realize what that is), I am certain that you will think of something fairly often—far more often than if you habitually decide “well, there’s just nothing I can do.”

If there’s a 1/14,000,000 chance of winning, nobody can look down on you for losing. But that doesn’t mean victory was impossible. You shouldn’t feel bad about losing a difficult match, but do not let your desire to avoid feeling bad lead you to conclude that it was “impossible” for you to find a way forward.

I don’t believe there is such a thing as “the other players are out to get me and there’s nothing I can do.” There’s always something you can do. It will be hard, it will be difficult, you might put in a ton of effort for a modest payoff, but there’s something you can do.

I have personally played a few matches of Diplomacy where I was initially attacked by multiple neighbors but eventually went on to achieve a solo win. In particular, I recall a match of Gunboat Diplomacy I played as England where I was initially attacked by France, Germany, and Russia (a common problem for England, which I’ve written about before). I quickly lost control of Norway and was reduced to just my home centers. But with good guesses, I blocked any player from getting onto Great Britain and waited for those players to attack each other, which they eventually did. I later got opportunities to pick at their supply centers, and gradually gained momentum that put me on the path to a solo win. In that match, I had to drill deep into my reservoirs of patience, persistence, and talent. I played at a level beyond what I normally apply to a gunboat match, and probably put more effort into surviving that initial attack than I put into the rest of that match or perhaps even any gunboat game I ever played. I was able to sustain that kind of effort because I believed it was possible for me to prevail so long as I had even a single supply center left.

A solo win isn’t going to happen every match. But at the very least, you can hold out long enough for someone else to attempt a solo, and then get yourself included in the draw.

It is possible to reach a game state where, yes, there are literally no moves you can make anymore to survive. However, the eventual existence of such a game state doesn’t mean that you were somehow destined to reach that game state; there must have been something you could have done earlier in the match that would have saved you.

4. Treat Every Match as a Test of Your Skill

There are players who adhere to the attitude I am criticizing even if they don’t use the word “luck” to describe how they feel. There’s this claim floating around the community that Diplomacy is a game where it’s really hard to control your destiny, so you can only really prove how good you are through long-term, aggregate results.

What a great story to tell yourself to help you sleep at night.

I’m here to tell you today that the outcome of any given Diplomacy match strongly corresponds to the difference in the skill of the players in that match. Sure, there are “upsets” where a weaker player ekes out a rare result against stronger players. But I think that happens in Diplomacy far less often than almost any board game, or competitive activity in general. Diplomacy is a game where being even slightly better than another player will make a huge difference in your ability to defeat that player. If you are significantly better, the match is yours to lose.

For example, consider my personal Diplomacy league (a gunboat league). Most of the participants are my friends and family. These players are not bad by any stretch of the imagination; my league is composed of intelligent, educated people who are capable of defeating me at other board games and video games. But the difference between me and one of my family members is staggering: of the 51 matches we have played together across several years, I won 17 times, drew 24 times, and was almost never eliminated (I even won as the C-Tier powers). In comparison, this player won 0 times and drew only 14 times. This is a person who plays board games as often as I do, conversed with me for hours on how to play Diplomacy well, and beats me almost every time at certain other games! This person isn’t bad and isn’t lazy; I’m just better at Diplomacy.

This family member I’m talking about, I think they stand a better chance of beating me at Magic: the Gathering than at Diplomacy, despite the fact that I have played Magic for about 17 years and they barely know the rules. I believe this because Magic is a card game, so there’s at least a chance for me to get truly unlucky. Luck plays no role in Diplomacy once the match starts.

5. Don’t Pretend You’re a God

When someone claims to have lost a game (any game) due to “luck,” I take that person to be saying that they couldn’t have possibly performed any better at the game. In other words, even with the benefit of hindsight, there is not one thing the player could have done differently to alter the outcome of the match. Somehow or other, random chance determined the outcome. Even if that player had perfect mastery over the game, even if they were a nigh-omniscient god who is almighty in all realms except the realm of chance, the match was doomed to be determined by a coin flip and that is the sole reason for the loss.

When can someone truly claim to have lost a game due to luck? Can anyone really say that about games that involve skill? If you’re playing casino games like Roulette or Craps, then yes—yes, luck determined whether you won or lost. There’s no doubt about it. But in nearly all games that have a mix of randomized information (the stuff that I’m saying is actually “luck”), it’s actually pretty uncommon for this luck factor to be dispositive as to who wins and who loses; there is usually something you can do to skew those odds more in your favor, or to overcome the odds.

You might counter: “Well, by definition, the optimal moves are the ones that would have caused you to win, so with hindsight you always know what could have been done differently.”

To that I say, that’s exactly what I’m trying to point out. You’re not omniscient; you’re not a god. Somewhere between your current capabilities and godhood lies the outer limit of what you can do, and you should strive to improve to reach that point… not blame “luck” for your inability to understand and foresee the best moves you could have made.

What is Luck? (Baby Don’t Hurt Me!)

An excuse.

If you read my blog, I suspect that you are an ambitious Diplomacy player. An ambitious player like you doesn’t need excuses. You have what it takes. Your destiny is in your hands. You can win and, if you strive to reach your full potential, you will win.

Thank you for reading!

Footnotes[+]

| ↑1 | ”Feeding” is a term I learned playing video games, and I don’t know another word for this concept. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A reminder, dear reader: uncertainty in what your rivals will do does not constitute luck. As I wrote in the companion piece, anticipating opponents’ choices is a skill. |

| ↑3 | I have written much more on the art of speculating about others’ hidden thoughts. Click here to read one of my philosophical essays on the subject. |

| ↑4 | The philosophical study of how words correspond to concepts is called Semantics. |

| ↑5 | Edit: My support for the Avalon Hill statement definitely riles up certain people; I have received a disproportionate number of messages about this piece, and my writing spawned huge conversations on other websites. |

| ↑6 | Counter-factual in their view, not mine. |

| ↑7 | Describing everything you feel is beyond your control as “luck.” |

Great post. I first played Diplomacy around 5 years ago and since have been playing in playdip site with 21 games, around 33% rate for solo/draw/loss each, press games only.

I agree with your notion that luck is an excuse for players to attribute their loss to. I hate the term ‘luck’ in Diplomacy, as I think luck should be used for situations where there is a concrete probability, like 1/6 in rolling dice or 1/30 chance of drawing a desired card from a deck of 30 cards. I prefer the term ‘environment’ which is the factor that you cannot control just like luck, but there is something you can do to improve the situation unlike luck where the only thing you can do is praying. You may have a neighbor who is silent, irrational, clumsy, newbie, or whatever. That is an environment that you are facing and you have to find what is the best thing you can do in this environment, rather than complaining ‘Why am I unlucky?’ which can be in my words, ‘Why am I in disadvantageous environment?’. The reason is simple; there is nothing you can do with it, the only thing you can do is drawing out the best outcome. The best player should always strive to achieve solo, and be able to achieve draw in any given environment.

I too strongly disagree with the argument that guessing is a part of luck. Guessing another player’s move and making my move is a combined skill of tactical intuition, understanding the other players’ tendency, assessing risk involved with my moves(future position and gains) and so forth. Another player’s move is not an uncontrollable factor since your words and action can have influence on this matter. It’s definitely hard to control others’ moves since you will always be lack of information, yet seeing my plan being successful and guess being right can’t be compared with any other joys. Guessing other players’ move is one of my most favorite part in playing Diplomacy, and I deeply feel disheartened to see someone saying this to be just ‘luck’.

I’m confident that I’m a skilled and competent player, yet I still have many things to learn. I recently learned from a skilled player regarding how to deal with minor power, and enlightened me on how to achieve solo, which is my biggest challenge in the game. I love Diplomacy because it broadens my insight on people and lets me learn lessons from every game. It was great to see a fellow player. 🙂 Hope we could discuss from time to time though I’m not really playing Diplomacy nowadays… It’s a frustrating, stressful game you know.

I really like this article.

Diplomacy is a game where it’s easy to feel like there’s nothing you can do – but there’s always something you can try, and in the words of my dad, “You’ll never know unless you ask.” It’s just often hard to take that mindset. My very first game of Diplomacy I drew Austria and was deceived by Italy and squashed between Italy and Russia. As it was happening, I remember feeling helpless, like there was nothing I could do… and yet there were probably several asks I could have made that might have helped… but I’ll never know because I didn’t ask because I didn’t know what to say. Afterward, it would have been easy to say, “Well, just bad *luck* I drew Austria” and move along…

…but I didn’t. I thought about it afterwards and tried to figure out where I went wrong, and that’s the important (and difficult!) part – holding up the mirror to your own failures, admitting them, and learning from them.

I don’t write them *quite* as detailed as you or some others I’ve seen, but one reason I enjoy writing end of game synopses is to do just that, so to speak, and see where I could have improved my play. I just finished a private game on WebDip where, as I was writing the analysis, I realized that if I had read a couple of players and their general mood on the game a little bit better near the end of the game I might have been able to reach the stalemate line faster and maybe gotten those couple of Iberian centers I needed for the solo.

(Speaking of which, after the biggest game of all time and the WDC game, which both went well for you, it would interesting to see an analysis of one of your games that went horribly off the rails and where you think you went wrong.)

Yes, I agree that luck plays no role. Players playing sub-optimally or dropping out may be annoying, but they are not luck. Although you cannot predict with 100% certainty that a player will go NMR or make irrational moves, you can sometimes spot telltale signs of this happening. Although you would prefer everyone to play with roughly equal skill consistently, and you might not feel good about taking an advantage of an opponent dropping out, it’s certainly within the realm of possibility and does not constitute luck. It’s certainly a factor that influences the game, but it’s not random. It’s connected to that player’s skill.

It’s also not bad luck if someone refuses to play along with my metagame idea of what his nation should do (which often seems to suspiciously coincide with him helping me get a solo win!). If I play Germany, I can read all of Richard Sharp’s book from the 70s (not knocking it, but just saying that it has a strong bias towards Germany, even in its chapters on other countries) and make all my plans based on what is “rational” according to it. But that does not put the other players under any obligation to play by that playbook as well. Maybe Italy would rather stay at 5 centres and stop me from getting a solo win, than to gain 8 centres but help me to a solo. Irrational? Hard luck? I don’t believe that, because my mindset is not that everyone else is a mindless sheep who only serves to do my bidding.