You know all the rules. You’ve played Diplomacy plenty of times before. Perhaps you’re actually quite knowledgeable and experienced about the game. Yet the coveted “solo win” still eludes you.

What are you missing?

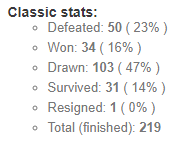

On my webDiplomacy account (created in Summer 2011), I have achieved a 16% solo win rate on the classic map. If every game ended in a solo win and each of the seven players had an equal chance, the expected win rate would be 14%. But roughly half of all Diplomacy matches end in a draw, so the expected average win rate is more like 7%.

My solo win rate of 16% is more than DOUBLE the expected win rate of 7%. What’s my secret?

Don’t worry — I’m here to tell you everything. In this series of posts, I will offer my sincere advice on how to achieve more solo wins in Diplomacy.

Forget the Numbers Game

In my opinion, weaker players overly depend on numbers-based heuristics (heuristics are mental shortcuts to simplify decision making). Let me go over some of them and why they are holding you back:

Fiction: “If I am increasing my supply center count, I am moving towards a win.”

Fact: More important than conquering particular supply centers is creating a future situation that will allow you to conquer the 18 needed to solo win. Although it is obviously necessary to conquer supply centers in order to eventually reach the 18 needed to solo win, every single conquest does not necessarily further that goal. Here are some instances of when conquering more centers will probably reduce your chances of getting a solo win in the long run:

If you make a land grab for more centers (such as by backstabbing a neighbor-ally) without having control (or the ability to gain control) of centers across your rivals’ likely stalemate line positions, you might foreclose your solo win chances because your high count of supply centers will trigger your rivals to unite against you and form a stalemate line.

- E.g., if you are playing as Turkey and Russia is your main ally, the best time to backstab Russia is probably on the same turn that you are certain to gain control of Marseilles, Spain, and/or Munich. Backstabbing Russia sooner might net you more centers in the short-term, but will hamper you in the long run. 1 defensible center on the other side of the stalemate line is infinitely more valuable to you than 6 Russian centers that aren’t part of your rivals’ future stalemate line.

If you conquer centers that are not defensible in the long run, you will create the temporary illusion of “winning” more, only to find yourself kicked out of those centers by another power at a later time.

- E.g., inexperienced Italian players frequently attack Austria early on (1901 or 1902), only to find themselves pushed out and eventually eliminated by a juggernaut alliance (Turkey and Russia).

- E.g., St. Petersburg is not permanently defensible from the south; a northern power (or combination of northern powers) will always be able to thwart a southern power if the game goes on long enough. If you are an eastern power (Austria, Turkey, or a Russia who only expanded south) and are counting St. Petersburg towards your total 18, you need to win around the same time that you capture St. Petersburg; otherwise, sensible rivals will have time to knock your unit out of St. Petersburg.

Don’t waste your effort fighting for centers that you can go back and get at a later time.

- E.g., consider the reverse of the St. Petersburg example I just gave: western powers (France, England, and Germany) can ignore an eastern rival who has control of St. Petersburg and is no solo-win threat. Instead, a western power interested in a solo win should focus on conquering key centers that can’t be easily gathered up at a later time (i.e., Tunis, Vienna, Warsaw) and come back for St. Petersburg at the end. More specifically, if you are a western power (probably England or France) and have secured control of all the western powers’ home centers + Tunis, your solo win has, in most instances, become inevitable; your rivals will be unable to stop you from reaching 18 by your conquest of Denmark, Sweden, Norway and St. Petersburg. Thus, a French player who is at 11 or 12 centers might actually be close to a solo win if those 11 or 12 centers include all the English home centers, Tunis, and Munich.

Fiction: “Two powers with the same number of supply centers are equally strong.”

Fact: Purely comparing the number of supply centers two powers control is naive, even ignorant.

First, the powers are not created equal. The corner powers (which I define as England, France, and Turkey) are difficult to attack from multiple directions. Accordingly, once those powers conquer some supply centers, they gain momentum that is difficult to stop. So when England, France or Turkey reaches 7 or 8 centers, they tend to become invulnerable. At 12 or 13 centers, they might be close to a solo win.

By contrast, the central powers (which I define as Germany, Austria, Italy and Russia; I go against the conventional wisdom here by defining Russia as a non-corner power) are easy to attack from multiple directions. It is difficult for these powers to gain momentum, because if they concentrate enough forces in one direction to actually make a breakthrough, they risk leaving themselves open to attack from a different direction. Germany, Austria, Italy and Russia can reach 7 or 8 centers and still be easily attacked by other powers. Even if they reach 12 or 13 centers, it is comparatively easy to stop them from getting a solo win because there is inevitably some gap in their positions that can be exploited to prevent a solo win.

Second, all supply centers are not created equal. Yes, each supply center counts as one “point” towards your 18 and allows you to build another unit—in this respect they are identical and equal. But each supply center is also a position on the Diplomacy board, and in this respect they are each unique and vary wildly in terms of how important they are.

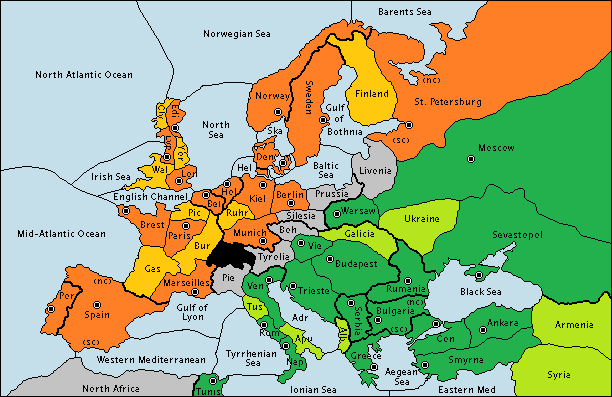

Supply centers that sit on the most common stalemate lines and are defensible from either side are, by far, the most important supply centers on the map. These centers are: Portugal, Spain, Marseilles, Tunis, Munich, Berlin, Warsaw, and Moscow (and to a much lesser extent, Vienna and Sevastopol). All other centers are significantly less important. The English and Turkish home centers are almost tactically useless during endgame because it is not possible to form a stalemate line through them; a determined power or coalition of powers will eventually get control of them all. Other centers are sometimes possible to incorporate into a stalemate line, but usually only if all or nearly all of them are firmly under control of a single power or alliance (like Scandinavia or the Italian home centers).

Thus, a division of spoils between England and France that gives Holland + Denmark to England and Munich + Berlin to France greatly favors France. Munich and Berlin have far more long-term strategic importance than Holland and Denmark, so it would be myopic to focus on the fact that each country acquired an equal quantity of supply centers. A similar comparison could be made to a deal where Turkey acquires Tunis and Moscow (essential, defensible, stalemate line centers) while Austria acquires Venice and Rome (centers from which Austria could, with relative ease, be displaced).

Third, what matters is not a power’s current count of centers, but that power’s capacity to hold those centers and to acquire more centers in the future. Unfortunately, this concept is hard to grasp abstractly and easier to understand through experience. What you need to learn to do is think several turns ahead.

When a player has enough units in position to capture a center by force, you should think of that center as being under that player’s control — even if that player hasn’t actually captured the center. Conversely, when a player has captured a center, but does not have the ability to defend it the next year against a counterattack, it is not really worth counting that center towards your mental sum of that player’s “score.”

When you are attempting to get a solo win, it is usually a wise tactic to actually bypass centers you are certain to eventually capture in order to get into more distant centers.

Fiction: “I almost won because I had 15/16/17 supply centers!”

Fact: Unless there was a turn where you could have reached 18 centers with corrected guesses (and simply made the wrong guesses), you did not “almost” win.

Because it is relatively easy for an anti-solo-win alliance to form a stalemate line that incorporates 17 centers, reaching a high number of supply centers is not really indicative of how close you were to winning. Indeed, in my opinion, this kind of thinking is probably holding you back. Your problem is that you are focusing on numbers and not the tactical and strategic implications of the particular supply centers you control.

There are dozens, if not hundreds of stalemate lines that incorporate 17 supply centers behind them. Unless you can viably contend for 18 supply centers (and by this I mean, create a situation where it is theoretically possible for you to make a guess that results in your control of 18 centers and a solo win), you probably never had a chance of winning. It’s just far, far too easy for an anti-solo-win alliance to form one of these stalemate lines if they see your solo win attempt coming.

Competent — but not excellent — Diplomacy players find themselves able to reach 15-17 supply centers reasonably often, but never 18. I’ll go as far as to say that “how do I do a better job getting from 17 to 18?” is the most common question I am asked by my students. To this I say: going from 17 to 18 is often impossible, because if you reached 17 supply centers you’ve probably given your rivals enough turns to form a stalemate line.

What you have to ask yourself before you attempt a solo win is: “Do I control (or have the ability to soon control) a defensible supply center on the other side of the stalemate line that my rivals will want to form?” If you can’t answer that question with “Yes” (either because you don’t have the position I’m describing or because you’re not experienced/informed enough to know what those positions even are), then you’re probably not going to solo win. Why won’t you win? Because you’ll reach 15, 16 or 17 centers, and then stop there. Your rivals will incorporate all the centers you might need to reach 18 into their stalemate line, and that will be the end of the match.

In my experience, what is happening to confused and deluded players who think that they “almost” won by reaching 15-17 centers (without any turn in which they have a theoretical chance at taking the 18th center) is that they’ve merely learned how to take over one side of the board. They’ve learned how to take over either the “northern” or “southern” half of the map, but have not learned how to “cross the stalemate line” before doing so. Let’s take a look, shall we?

So here’s the thing: once one power has control of more than 50% of the centers on a either side of this map (the majority of centers in the “North” or the majority in the “South”), it is relatively easy for that player to take over the rest of that side. But each side only adds up to 17 centers, so a victory can never be achieved simply by dominating one side of the map.

Some powers have an easier time getting a few centers on the opposite site (e.g., Germany can easily get Warsaw and Moscow; Italy can easily get Marseilles and Spain), but this is offset by a difficulty in gaining an equal number of more distant centers on their own side (e.g., Germany has a hard time capturing Portugal and Spain; Italy has a hard time capturing Warsaw and Moscow). For any given power, there are 15-17 centers that are relatively easy to capture, and 2-5 centers that are difficult-but-possible to capture.

So in other words, if you find yourself getting to 15-17 centers fairly often without ever getting a solo win, it is probably because you’re focusing on easy-to-capture centers and increasing your number of supply centers rather than focusing on difficult-to-capture centers that will actually create an opportunity to get a solo win.

Play More Draw-Size Scoring Matches

Before ending this post, I’ll take crack at my whipping boy: Sum-of-Squares scoring. I think Sum-of-Squares scoring is an inferior scoring system for Diplomacy and I avoid it if I can. I didn’t think of this when I wrote my post about why I don’t like that scoring system, but I’ll say it now: it teaches newer powers to focus on the sheer quantity of supply centers under their control, which misleads them into thinking that capturing another center is per se the objective of the game. In Draw-Size scoring, there are only three amounts of supply centers that matter: 0 (elimination), 1-17 (draw), and 18 (win). In Draw-Sized scoring, capturing 17 supply centers is not recorded as a “better” result by the scoring system than 16 or 15 — and in my opinion, this is a boon, because I don’t think that reaching 17 is a “better” result than reaching 16; 17 is not a win.

Stay Tuned!

This is the first of a series of articles I am writing on how to get more solo wins. I am just bursting with tips for players who want to learn to be better at Diplomacy, and the only thing holding me back from writing more is that Diplomacy is simply a hobby of mine and I have a job, a life, etc. that have to come first. As soon as I get another free evening, I’ll write another post!

[Edit] And I eventually did! Consider reading my second article in this series: Solo Win Tip #2: There’s No Such Thing As Luck

Hi! Just recently came upon your site in search of information on Diplomacy, the game.

So far I found your writing very helping. Thing is, I just recently discovered this game, and am frantically trying to get better at it.

I wonder. Would you be willing to go over my games in spare time to point out mistakes, suggest better moves?

It could also become an article for you. “Noob mistakes, or how to avoid pit-traps” or something.

In any case, would love to hear from you.

Satoshi, I am glad you find my writing helpful. Thank you for telling me!

I am absolutely willing to review your games. Many players reach out to me for that kind of help, and I gladly provide it. I like your idea that I could post my tips for you as a noob-friendly article. I will contact you by email!

Thank you!

I have doubts about leaving a correct email address, so going to write again, just to make sure I input it correctly.

Your thoughts on the difference between 17 and 18 centers are very interesting, thank you. I was surprised by the idea of bypassing centers though, could you give some examples of that? I’m picturing a Turkish player rushing past enemy-occupied Vienna or Naples to get to Munich or Tunis ASAP; are those bad examples? Is ignoring Venice to get to Munich a more realistic interpretation? I find that I focus on incrementally taking centers towards dominating a half, but part of that is a motivation to have a coherent defensible line myself without the ability of an opponent to sneak behind or otherwise interfere with me. I’m radially expanding outwards. Stretching for a difficult center kind of feels like I’d leave myself open to be flanked.

Yes, you’re right on the money! Turkey is a great power to choose as an example for rending this concept into practice, because Turkey starts furthest from the stalemate line; Turkey’s position puts a high premium on key centers like Munich.

I’d bypass Vienna, Venice, or Naples to get to Munich, definitely. I might prioritize getting into position at Munich and Berlin over capturing a home center; Turkey might be able to solo without control of Smyrna and armies behind the stalemate line, but Turkey will never solo without penetrating the north somehow.

It’s true that stretching your forces is taking a risk, but wisely taking risks is how you will solo win more in Diplomacy. In a low-level match, where the players cannot be counted on to know what a stalemate line is or how to form in (or for that matter, to even finish the match), conservative play like you describe is a reliable way to get to a win; if you simply do not lose and keep growing, you will likely eventually win. But in a high-level game of Diplomacy, one where all the players understand how to play and can be counted on to finish the match, that strategy will rarely (if ever) lead to a solo win. “Playing to not lose” is good when not-losing will lead to a win, but you need to take risks and “play to win” if you are to solo win against experienced players.

In other words, the conservative style of play is wagering that the other players will be unresponsive during the decisive endgame turns, either because they are foolish or because they have stopped caring. The kind of play I am advising greatly raises the chances of soloing in endgame—even against players who know what they’re doing. The key to getting it to work is being judicious about when and where to take the tactical risks.