Data journalist Dave Ainsworth presents an analysis of a Diplomacy data set. Listen to Dave discuss his analysis and answer questions at the vWDC Masterclass session here.

Here’s a thing I hope we can all agree on. In order to solo a game of Diplomacy, you usually need to eliminate other players.

But which ones? And, perhaps just as importantly, which ones do you want to survive?

Some answers to these questions lie in a wonderful data set collected around 15 years ago by Josh Burton.

Burton collected a big data set of games, and published a number of studies into that data, looking at which countries win most, which centres you want to hold, and what happens in a solo. If you’ve never read Burton’s original articles I really recommend doing it. I found his stuff halfway through my first ever game after I realised I was way out of my depth, and it helped me get in the draw instead of flat-out losing.

Most of the credit for this article therefore goes to the outstanding original data, but I did some more digging into the figures because I wanted to know more about what happens in a solo win. I think I found some things he didn’t mention.

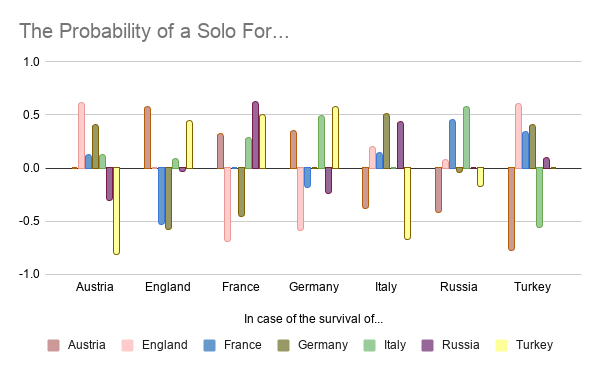

In particular, I took a look and I produced this chart which shows whether your chances of a solo go up or down, if another country survives.

Basically if the bar is above the line, you’re more likely to solo if that country survives. So typically if you’re Austria you’d solo roughly six in every hundred games. But if Turkey survives that drops to about one in every hundred.

The arithmetic is a little complex due to the different elimination rates of different countries, but we can oversimplify and say that’s roughly an 80 per cent fall. So if you’re Austria, you probably need to kill Turkey.

On the other hand if you’re Austria, your chances of a solo go up by 60 per cent if England survives.

So I want to talk about a few things that I think do and don’t support the conventional wisdom.

Antagonistic Relationships

One thing you can see is that there are a number of highly mutually antagonistic relationships on the board. Austria has to kill Turkey, and Turkey has to kill Austria. Both solo only one in every hundred games if the other one survives. Turkey in particular has to control almost all centres on its own side of the stalemate line if it wants to solo, so it’s no surprise that it needs to kill Austria.

England and France are the second most antagonistic pairing, but still far lower than Austria and Turkey. Third is Italy and Turkey. Fourth is England and Germany.

One thing that is interesting to me is the perception in the game that England and France, the second most antagonistic pairing, are also an incredibly natural alliance, who can work together the whole game to crush the board.

We can’t talk about all the pairings, but you can oversimplify a bit, and say that basically you usually want the countries that are near you to die (presumably because you killed them) and the countries that are far from you to survive.

This is pretty much common sense, I think, but what is interesting, and not intuitive, is just how much a solo appears to be dependent on the survival of lots of powers. It’s clear that if you want to win, it looks important to have as many other countries survive as possible.

The Stalemate Line

Another thing this data really brings home to me is how much the stalemate line matters.

Geographically, the main stalemate line is an incredibly powerful force in Diplomacy, maybe the most powerful, despite being invisible to many players. To me it explains so many elements of the game.

I think of the stalemate line as a warped mirror, and I think the data reflects this.

Traditional wisdom divides the board into three central powers which underperform – Germany, Austria, Italy – and four corner powers which overperform. The corner powers apparently do better because they’re protected by the corner.

I think this theory is at least partially wrong.

Here’s a map showing the stalemate line. It’s the dark blue area.

As you can see, the two sides mirror each other closely. Roughly half the provinces on the map lie on each side, although there are a few more sea provinces in the north.

Each side of the stalemate line has a corner power (England and Turkey) and a central power (Austria and Germany). Then there are two powers which share a corner (France and Italy). And then there’s Russia, which is on both sides of the line.

I think the board is misleading because visually, Italy’s almost slap bang in the middle. But that’s because of some massive great provinces in the top corners. If you look at a map with the idea that the dark blue line really runs from corner to corner, you begin to see that Italy and France occupy identical places on opposite sides of the stalemate line.

So the line’s a mirror. But it’s a warped mirror because Russia’s more in the south. It’s got three centres in the south and one in the north.

What does that mean? It means that there are less neutrals in the south, and more units fighting for those neutrals, so it’s a tougher environment to operate in.

You’d expect to see that reflected in the scores, and indeed you do. In the Burton data set, England, France and Germany all have better results than the mirror power on the other side of the line, although in the case of England and Turkey it’s very close.

If we go back to the graph at the top, you can see how similar the preferences are of mirror powers across the line. Take Italy and France. They both want Russia to do well. They’re ambivalent to each other, they both want the death of their own corner power, and the survival of the opposite corner power.

As a slight aside, this is particularly interesting to me with regard to Italy. Some people say that Italy’s not a southern power or a northern one, but rather between the two theatres.

That’s not really true. It is true that Italy is the second most likely power to operate in both theatres, after Russia, but in a typical solo Italy gets three quarters of its centres in the south (13.5 in an average game) so it is definitely a mostly southern power. Russia, for comparison, gets roughly two thirds of its solo centres from the south (11.5 out of 18 in an average game)

Italy is really a Mediterranean power. If you look at a typical Italy solo, there’s not a single centre more than two moves away from warm blue water.

Anyway, to get back to the main topic in hand, we can see that the mirror powers on opposite sides of the line have relatively similar preferences about who they want to kill and have survive.

The corner powers, England and Turkey, pretty much have to kill both the powers on their own side of the line stone dead. So do the half-corner powers, Italy and France.

Germany and Austria have to kill the corner power on their own side of the line, but they’re not that fussed about France and Italy. They’re more worried about Russia. Austria actually does better if Italy survives, Germany only does slightly better if France dies.

Russia, meanwhile, is unique. Russia is fine with pretty much everyone surviving. It does a bit better without Austria and Turkey, but it’s not vital. Russia does do well if both France and Italy do well.

Who You Want to Survive

Which brings us to the most interesting thing about this data. For most countries, who survives is as important as who dies.

What we see is how vital it is to all northern solos for Turkey to do well. And how vital it is to all southern solos for England to do well.

As I mentioned earlier, we see that solo chances are generally heavily improved by keeping almost all powers on the board for as long as possible, particularly on the far side of the board. This obviously makes sense. What you want is for the far side of the board to be mired in inconclusive conflict for as long as possible. You want to do everything you can to keep that happening.

But keeping the corner power on the other side of the board alive is particularly important. Turkey and Austria see a 60 per cent rise in their solo rate when England survives. All northern powers see a 50 per cent rise in their solo rate when Turkey survives.

I had to do a couple of calculations, so I’m not certain of this number, but I think the survival of England may actually be a bigger factor in Austrian solos than the death of Turkey.

All Austrias know that you have to kill Turkey, right. But killing Turkey may actually have less impact on your chances than keeping England alive? That would mean that just about the single biggest factor in an Austrian solo may be the survival of England.

The same is true with Germany and Turkey. And this is particularly interesting, because Austria and Germany are often perceived as best buddies. But really, if you’re Germany, and you’re allowed to preserve a purely southern power, Austria is arguably the least important one to save.

In general, this holds true, right across the board. When it comes to a solo, what happens far away matters just as much as what’s nearby.

If there’s a coherent lesson here, then it’s this: make it an extremely high priority to keep alive the power you’re furthest from.

Pingback: Diplomacy Dojo Episode "Who Do You Need to Kill?" with Dave Ainsworth (vWDC Masterclass April 2021) – BrotherBored

Dave, as per usual, another excellent article. Based on the findings, it is clear that a power wants the power on the other side of the board to survive. So, for example, England and Turkey both want the other to survive. Since that is the strategic objective, the challenge becomes, how are you best able to influence the situation to help ensure that outcome, especially in the early game? Said challenge is made more difficult in that you are not close to the action so are physically less able to directly ensure this result. However, to ignore that objective is counter productive. A suggestion for a future article, therefore, might be, “Strategies to advance the survival of a power on the other side of the board.” While I have some thoughts on the matter, hearing yours would be most instructive.