This is the third entry in a series of articles describing the reasons why players backstab you in Diplomacy—and what you can do to reduce your chances of getting backstabbed!

Click here to read about reason #1, “You were Annoying.”

Click here to read about reason #2, “You were Troy.”

Reason #3: You were Servile

While writing this blog for the past couple of years, I have occasionally referred to what I call “servile allies.” What do I mean “servile ally?”

In Diplomacy, you cannot win without forming alliances. But you also cannot win without betraying those alliances. As triumphant allies become mightier with every supply center they capture, their strategic incentive to backstab each other grows larger and larger. Thus, the success of every alliance sows the seeds of its own destruction.

To play as a “servile ally” is to overlook the threat that your successful alliance poses to you.

Want to learn how to NOT be a servile ally? Keep reading! I have 4 tips that might help you out.

Do You Just Wanna Be a Care Bear?

I have played Diplomacy on-and-off for about 10 years. I can assure you that “Care Bears”—players who refuse to backstab a friendly, reliable ally even at the cost of their own success—do exist. So there will be times when showing your absolute trust and faith in an ally will be rewarded with the same response from that ally.

or Scare Bear?

But can you perceive the difference ahead of time? Can you tell the difference between a player who is Care Bear and a player who impersonates a Care Bear? Because let me tell you, I think it is very easy to impersonate a Care Bear. I do it all the time. My allies are shocked—shocked—to be backstabbed by a player who in every way acted and sounded like a Care Bear.

It doesn’t matter whether you will act like a Care Bear or not. The question to ask yourself is: “Is my ally really a Care Bear?”

As I wrote in my article The Top 5 Strategic Goals in Diplomacy, players commonly—and rather easily—obscure their strategic goals by falsely asserting goals that they do not actually seek.

So what though?

Let’s say you have come to believe your ally is a Care Bear. So what? A Care Bear can be a great ally. To that I say: true. I myself often look for Care Bear allies.

Well, the danger does not come from the fact that a player is (or presents as) a Care Bear, but rather from how you might choose moves that place you in a tactically vulnerable position as a result of putting your complete faith in that ally. That decision can be—and often is—a fatal tactical blunder.

In other words, you face danger not from your ally presenting as a Care Bear, but from choosing tactics that assume your ally will never be a threat to you. Playing in a way that assumes your ally is no threat to you is the essence of “servile” alliance play.

Servility Can be Subtle

Like the soft hands of a new laborer that blister and bleed until they become thickened through use, the naïve thinking of a new Diplomacy player develops a grizzled paranoia through the experience of rough matches. Veteran Diplomacy players—calloused by their experiences of misplaced trust—are not that credulous of self-described Care Bears.

But even experienced players nevertheless make subtle tactical mistakes that I deem servile alliance play.

If you’ve played a few Diplomacy games, then I bet you’ve seen it happen. I bet you’ve felt it firsthand. What am I talking about? It happens in that initial moment of beholding the game board on the turn when a player’s treachery is revealed. I’m talking about immediately realizing—after the moves are revealed, of course—the precise tactical way a player could (and did!) execute a devastating backstab. That moment where you think “I didn’t see that coming! But in hindsight, it is obvious.”

And to be clear, I don’t mean a reaction like “I expected that player to choose different moves!” I’m talking about a reaction like “The possibility of that player choosing those moves did not occur to me! I never even considered it.” This is a common moment in Diplomacy matches. And I think the oversight is a product of subtle servile thinking.

I am fascinated and excited by my observation here. A mistake that even experienced players make must be important—and a mistake that is easy to recognize in hindsight should be easy to avoid with foresight, right? Accordingly, I think that the solution to this mistake should be easy to learn and that doing so should improve your gameplay quite a bit. Thus, you might improve a lot at Diplomacy with minimal effort. Read on!

Tip #1: Drop the Word “Ally”

Lord Palmerston (speech, House of Commons, 1848)

Your Bored Brother is here to tell you that your words matter. A lot. This is because, most of the time, you think in the form of words. The thoughts are the words and the words are the thoughts.

I have often experienced a moment where learning a new word or phrase made me capable of new thoughts.[1]For example, I recently learned about the concept of “Technical Debt.” My life will never be the same. Expanding one’s thinking and expanding one’s vocabulary are closely interrelated.

Similarly, sloppy thinking and sloppy language are often one and the same. For example, I know someone who describes almost every person he meets or knows as his “friend.” I myself am frequently confused about the strength and extent of his relationships with other people…and I think he confuses himself too!

Words are a tool you use to think. You can improve your thoughts by improving the words you use to think those thoughts. Better tools, better work. Clearer words, clearer thoughts.

So, here we go: stop thinking of players as your “allies.” Use different language. Try something like “cooperative rival.”

Really. Truly. This simple change in terminology might make a difference.

Tip #2: Try on Thinking Caps

To successfully imagine the ways your “cooperative rival” (possibly in combination with other players!) could backstab you…

- Imagine yourself playing as that power. Forget about what power you are currently playing.

- Assume you are trying to attack/backstab the power you are actually playing. Forget what you know about promises, alliances, player tendencies, etc.

- Imagine 3-5 attack scenarios. That’s right, don’t just stop at one! Diplomacy is a tactically complex game, and there are usually many different tactical methods by which one power could attack another.

Then repeat this process for each rival you are cooperating with.[2]Actually, I recommend doing this kind of analysis for every power every turn—allies and enemies alike! You can get pretty far in predicting (and therefore countering) any player’s moves this way. But I think most players already imagine ways for their enemies to attack them; what they … Continue reading By this method, you should be able to imagine all sorts of terrifying scenarios.

Now ask yourself: what are you doing tactically (not just politically!!) to prevent or deter these attacks?

Your Fatal Mistake: Dropping Your Guard

In Diplomacy, it is usually possible to move all your units in the same direction. This typically means sending units toward one power (a targeted rival) and away from another power (a cooperative rival).[3]I’m enjoying testing out this different terminology in an article! Examples:

- France, when cooperating with England, might move all French fleets into the Mediterranean.

- Austria, when cooperating with Italy, might move all Austrian armies east and north.

- Turkey, when cooperating with Russia, might move the starting Turkish fleet through Constantinople and into the Mediterranean (and send all other Turkish units west).

There are many tactical and strategic reasons why a player might want to move their pieces this way. I am not about to condemn all trust! But there comes a point where a power has moved their pieces too far away from their home centers, such that a suddenly-uncooperative rival[4]Also known as a “traitorous ally.” would be able to backstab without facing any retaliation. This is what I am calling “dropping your guard.”

When you drop your guard, you give your rival the tactical ability to attack you without facing any immediate consequences or even resistance. If your cooperative rival is truly a Care Bear, then of course they will not attack. But if your rival is anything less than 100% a Care Bear…you will have created an enormous temptation for that rival to backstab you. Indeed, even some players who generally do not backstab their allies may find your defenseless posture too tempting to resist!

Thus, dropping your guard can be your fatal tactical mistake.

Tip #3: Keep Up Your Guard

“Keeping up your guard” does not mean playing defense at all times. It means keeping a small number of units (like one or two) in positions from which they are theoretically capable of either blocking attacks from a suddenly-uncooperative ally or retaliating against them.

In my experience, the opportunity cost of maintaining a small defense (even a theoretical defense can be enough!) is very slight compared to the danger invited by defenselessness. In Diplomacy, in pays to stay paranoid.

How do you know if you are keeping up your guard? The test is very simple:

“If my rival were to backstab me, would I be able to retaliate somehow? That is, would I be able to defend myself, or at least, make that traitor’s life hell until I am eliminated?”

If the answer to that question is unequivocally “yes,” then your cooperative rival will probably not backstab you. Backstabbing is risky and has lasting consequences on a player’s in-match reputation.

If the answer to that question is “I’m not sure” or “no,” then your rival is probably thinking about backstabbing you. There are only so many turns per match where it is convenient to backstab, and so your typical experienced (ruthless!) player thinks long and hard about seizing a good opportunity to backstab a defenseless player.

Example: ODC 2019 Round 2, Game 3 (Semi-Finals) (Aug 2019—Nov 2019)

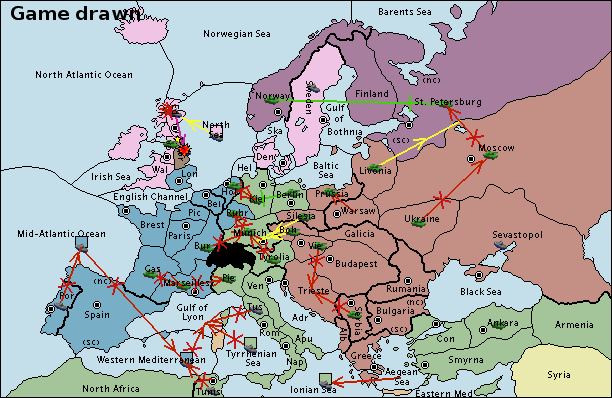

In this tournament match, I played as Italy. Austria and I cooperated with each other from the beginning to the end of the match. We ended the match as the dominant two powers by a hefty margin:

Are you surprised to see the Italy/Austria alliance taken this far?

I am certain that some newer players will find this map shocking. Italy and Austria are the only powers with adjacent home centers. In many matches (especially with inexperienced players), Italy and Austria attack or backstab each other very early. Indeed, I understand that these two powers were once called “the weak sisters” in the old days of play-by-mail magazine Diplomacy.

What happened here? Well, you can’t dismiss this example as two Care Bears finding each other. First of all, one of the players was me, Your Bored Brother, and I am ruthless. Second of all, this was a tournament match! Both of us were experienced, formidable players who wanted to end the match with a large score.[5]Indeed, the Austrian player in this match missed the final table by a sliver of points. I believe his taking even one more center in this game would have been enough to qualify for the finals!

In my assessment, both Austria and I played in such a way as to prevent the other from getting a good backstab opportunity. On almost every turn, Austria and I each kept one or two units in non-threatening defensive positions. Just look at the final map to understand: see how I (Italy) kept an army behind in Ankara? See how Austria self-bounced Vienna and Serbia at Trieste? Those decisions are examples of keeping up one’s guard. Each of us used simple, low-opportunity-cost moves like these to deter the other from backstabbing.

As a game inspired by Cold War era nuclear war planning, it has a lot to say about mutually assured destruction.

Although it was possible—even on the final board—for one of us to backstab the other, such a betrayal looked likely to end in mutually assured destruction. Speaking just for myself: on several turns, I thought really hard about whether I could get away with backstabbing Austria (to attempt a solo win), and each time I decided against it. I decided against backstabbing because I thought the most likely result of such a betrayal would be a French solo win. I predicted that outcome because Austria had clear ways to defend against my attack, and clear ways to get revenge against me by throwing the match to France. (Indeed, the Austrian and I politely pointed out our mutual ability to do that on a few tense turns.)

Click here to read more of my post-game thoughts on this match.

My heuristic for backstabs goes something like this: “If you stab your ally, you better stab them dead.” I advise against backstabbing a player who will have a recoverable position—or be in position to retaliate—on the following turns. Many wise players abide by this rule of thumb, which is why keeping up your guard will deter them from backstabbing you!

Tip #4: Take It Slow

It seems so far ago

I don’t know if I’m ready

I’ll take it slow

Take it slow

Take it slow

Out and around we go

We’ll take it slow

This advice is simple: do not make (and do not agree to make!) moves that risk everything in the first couple of turns.

Now let me elaborate. In my previous entry in this series, I warned about Trojan Horse alliances and gave advice on how to recognize Trojan Horses. Obviously, if you think a player is trying to Trojan Horse you, you should choose defensive tactics to counter their hostility. In this entry, I am advising you to keep up your guard (to a moderate degree) even if you trust your rival! That’s because (1) keeping up your guard will give you some protection against Trojan Horses that you fail to detect; and (2) a moderately defensible position will deter backstabs.

Diplomacy is a complex game and a given match can last a long time. You do not need to throw all your pieces in one direction during the first two or three years. As long as you maintain a salvageable tactical position, future opportunities will come along. But if you get smashed by a devastating backstab, you will probably be ground down and eliminated (even if you technically hold on to a few supply centers for a turn or two).

Take your time and get to know your rivals. Give your potential allies several small opportunities to demonstrate that they deserve your trust before taking big risks on those players. Ease your way into an alliance by asking (and granting!) small favors to each other. Actions speak louder than words.

To understand this concept better, read my article An Autopsy of France: Lessons from the ODC. In that post, I gave my opinion that my French rival erred by choosing overly-trusting moves in Spring 1901. The French player never recovered from that disastrous opening. I argued that this predicament could have been avoided by choosing a standard French opening.

By the way, one of my rivals in a subsequent ODC match read and followed my advice from that very article…

Example: ODC 2019 Round 2, Game 7 (Semi-Finals) (Aug 2019—Oct 2019)

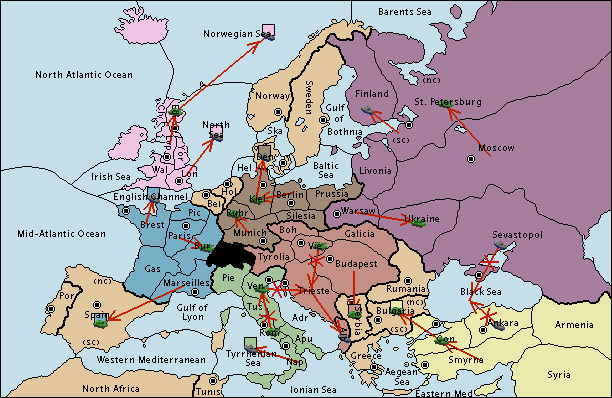

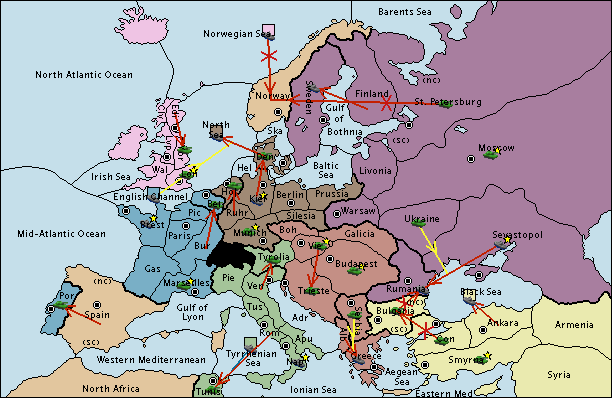

In this match, I played as Germany. In Spring 1901 (that is to say, before any players had moved their pieces), I conspired with the French and Russian players to deploy the anti-English “Sealion” opening.[6]The “Sealion” monicker is a reference to a never-used German World War 2 military plan to launch an amphibious invasion of Great Britain.

I will write much more about this match in the future. For this article, I want you to focus on just one thing: even though France believed that I was going to execute the agreed-upon Sealion plan (the French player said as much during and after the game, and I have no reason to doubt this account), and even though both of us in fact executed the plan…

…I still approve of France’s initial decision to move the army at Paris to Burgundy in Spring 1901.

As you can see from the map above, I (Germany), France, and Russia precisely executed all the Autumn 1901 moves called for by the Sealion opening. We also told the English player what they needed to hear to fall for this trap (e.g., the English player could have moved the fleet at North Sea to Belgium or Holland to block our moves, but did not.)

Let’s back up now for a moment.

The most well-known version of Sealion involves France opening by moving Paris to Picardy (instead of Burgundy) in Spring 1901. But I commend the French player’s decision to move through Burgundy (instead of Picardy) on the way to Belgium. France moving the army through Burgundy:

- Minimized France’s tactical danger. Consider France’s opening holistically. Neither Germany, nor England, nor Italy could individually exploit France’s Spring 1901 move set, and no theoretical combination attack could immediately destroy France in 1901. If France had chosen to leave Burgundy open, that would have been an enormous, unnecessary risk. (Leaving Burgundy open in Spring 1901 is always a risk for France, but the danger is particularly serious in combination with opening to English Channel and Spain).

- Cost France nothing tactically. The Autumn 1901 result was unaffected; France’s army moved into Belgium just as easily from Burgundy as it would have from Picardy. France’s contribution to the Sealion opening worked as intended. and since both of us believed the other that we were telling the truth about our intentions (and we in fact were telling the truth!) to execute Sealion…by Autumn 1901 it made no tactical difference that France had passed through Burgundy instead of Picardy.

- Did not hurt France’s alliance with me, Germany. France got my prior approval for the move to Burgundy.

- Slightly obfuscated our Sealion plan from England! If France had opened to Picardy, then the Sealion would have been completely obvious; France’s objectively hostile move to towards me, Germany, gave me useful credibility towards manipulating England’s choice of Autumn 1901 moves. Click here to read more about using tactics to hide strategy.

- Gave France options. What if the Spring 1901 opening moves caused France to want to chicken out of the Sealion opening? From Burgundy, France had tactical choices for Autumn 1901 that would not have been available from Picardy—such as moving Burgundy to Munich, or covering Marseilles against an Italian attack! (I know that having an army in Picardy would have opened up the possibility of convoying to Wales or London in Autumn 1901, but I think that option holds little strategic value because that just gives France a second way of attacking England. Burgundy gives France the ability to attack Germany or defend against Italy.)

I believe that this example—where a player kept up their guard and faced no consequences for that—should encourage you to choose low-risk tactics in the early game.

I think some inexperienced players are nervous to keep up their guard because they think prudent, low-risk, defensive tactics will somehow alienate their potential allies. I concede that sometimes this is true. But I believe it is better to be safe than sorry—especially if you find yourself getting backstabbed a lot in the early game.

But perhaps more importantly, I don’t think it is wise to ally a rival who will not tolerate your moderately guarding yourself against backstabs. Even if the alliance is not a Trojan Horse, your rival will be tempted to exploit your defenseless posture sooner or later.

What If You Are Cornered?

Sometimes you have little choice but to place your full faith in one player or another. This happens most often when you are losing. Something like this: you are in a position where you can put up a solid defense against Power A, or a solid defense against Power B, but if you try to defend against both that is tactically the same as defending against neither. So you have to pick! This situation does happen, and when it does…to be honest, you are at very high risk of getting backstabbed.

I point this out as an exception to my advice because there really are situations where you have to place your complete trust in one player or another. When that happens, I advise you to assess which player seems more reliable (considering the personalities of the players as well as which player has the bigger strategic incentive to actually help you) and go all-in. With your press, do everything you can to motivate that player to help you (including indirect efforts to manipulate them through third parties). But “how to talk your way out of a losing situation” is a topic for another day!

There’s more to come!

So you’ve decided you won’t play like a servile ally ever again. You’ve internalized my aphorism, “Every successful alliance sows the seeds of its own destruction.” To improve your play, you are going to follow my four tips:

- Drop the Word “Ally”

- Try on Thinking Caps

- Keep Up Your Guard

- Take It Slow

Good for you! You’re probably going to get backstabbed just a little less often.

But somehow, you know that’s not always going to be enough. You know that players can still turn against you even if you make it tactically difficult for them to do so! After all, Your Bored Brother finds ways to backstab allies that appear tactically well-defended…

Don’t worry! There will be two more entries in this series, each describing another one of the top 5 reasons players get backstabbed in Diplomacy—as well as how to avoid and overcome those problems in your own games!

Footnotes

| ↑1 | For example, I recently learned about the concept of “Technical Debt.” My life will never be the same. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Actually, I recommend doing this kind of analysis for every power every turn—allies and enemies alike! You can get pretty far in predicting (and therefore countering) any player’s moves this way. But I think most players already imagine ways for their enemies to attack them; what they forget to think about is ways their allies could attack them. Hence, I place my advice in this article about backstabs! |

| ↑3 | I’m enjoying testing out this different terminology in an article! |

| ↑4 | Also known as a “traitorous ally.” |

| ↑5 | Indeed, the Austrian player in this match missed the final table by a sliver of points. I believe his taking even one more center in this game would have been enough to qualify for the finals! |

| ↑6 | The “Sealion” monicker is a reference to a never-used German World War 2 military plan to launch an amphibious invasion of Great Britain. |