Introduction: The Game Skill Called “Yomi”

Diplomacy is a game that tests many skills. Among the more tactically-oriented skills tested by Diplomacy is each player’s ability to “outguess” their rivals. Because Diplomacy asks players to enter their orders simultaneously, players must choose their moves without knowing what the board state will look like as those moves are executed. A successful Diplomacy player anticipates their rivals’ moves and incorporates that predicted information into their line of play.

I call this skill “yomi,” a term I picked up from game designer David Sirlin and the fighting video game community.[1]Examples of the “fighting game” genre include Street Fighter, Mortal Kombat, and Super Smash Bros. I use this Japanese loanword to refer to the art of “reading the mind” of an opponent. This is not a supernatural concept; I’m talking about anticipating someone’s actions by understanding how they think.

Although most games test the players’ yomi ability to a certain extent, not that many strategy games emphasize this skill. For example, perfect information games like Go and Chess do have a little bit of yomi involved (a player can choose a move based on how they anticipate a particular opponent will respond), but the yomi-testing aspect of those games is typically submerged under an ocean of valuation-testing. By “valuation,” I mean testing a player’s skill at evaluating the costs and benefits of different choices. To learn more about how Diplomacy tests the skill of valuation, read Solo Win Tip #1: Forget the Numbers Game.

I love games that test yomi.[3]Do I love games that test yomi because yomi is my best skill…or did yomi become my best skill because I love and play so many games that test it? Diplomacy is among my favorite games because this skill is such a large part of the gameplay. One of the reasons I love Gunboat Diplomacy so much is that the no-talking rule boosts the importance of yomi to stratospheric heights.

Yomi is one of the core skills tested by Diplomacy. If you can learn how to read your rivals’ minds, your ability to solo win will be much greater. Also, it’s just plain fun!

I, Your Bored Brother, possess a tremendous yomi talent. My ability is so strong that I have achieved a lot of success in Diplomacy despite my weaknesses in other skill areas.[4]For example, for something like 8 years I thought Munich could be stalemated from the south without Berlin…that is factually false, and not difficult to figure out. Somehow, this ridiculously wrong belief did not prevent me from playing matches well. And that’s just one example! Fortunately for you, dear reader, I also posses the ability to write lucid articles and a desire to teach people what I know! This article is written for a beginner—it only scratches the surface of how the yomi skill works and how to develop it—but you’ve got to start somewhere, right?

Let’s learn more about yomi.

Yomi is Based on Empathy

Reading minds requires no inborn talent, and definitely requires no supernatural talent. Yomi relies on your powers of empathy—your ability to think “what would I do if I were this person?”

I worded the rhetorical question carefully. You are not asking yourself “what would I do if I were in that situation?”—you’re asking “what would I do if I were them?” You are becoming a kind of actor, inhabiting the mind of a character (the other player). When you can accurately imagine what you would do if you were the other player, then you can predict their actions! It’s as simple as that.

Of course, simple does not mean easy.

Step 1: Model the Other Player’s Mind

Let’s talk about a foundational yomi technique: modeling the other player’s mind.

First, taking into account everything you know, create a base model for the other player’s mind. Ask yourself questions like this to make your base model:

- How do Diplomacy players think, in general? Remember: your own thoughts—and your normative beliefs about how players should play—are not a factor here!

- What caliber of player am I dealing with? Or, if playing anonymously, what caliber of players have joined the match? Beginners think about Diplomacy differently than moderate players, and experts think differently yet still!

- Do I know anything about how this particular player thinks? Maybe there’s something you’ve learned about their reputation, or from having played with them before. Consider also their initial press and choice of opening moves.

This is information you know before the match or can learn as the match starts.

So for example, let’s say you start a new match. You are aware that all your rivals have played some Diplomacy matches before, and so they have a certain minimum level of experience. Is Austria going to open Trieste to Adriatic Sea? Probably not! Only the most inexperienced players think to move Trieste to Adriatic Sea as their first move (usually with a shallow thought process like “boats should go into the water”). You can make this prediction this solely from your knowledge that all of the players have some experience!

Let’s say, on the other hand, that you are uncertain about the experience levels of the players. If you witness Austria open Trieste to Adriatic, that provides some evidence that this player might be playing their first-ever Diplomacy game, or is at least playing Austria for the first time.

This base model allows you to make all sorts of inferences (and predictions!) about how the other players will pursue the match. However, it’s not perfect. Player deviate from norms and conventions for subtle reasons—including faking that they are inexperienced! So, there is more work to be done as the match unfolds.

Role Play by Narrating their Thinking in their Words

This technique is not for everyone, but I find it helpful and I know some of my students have found it helpful too. To employ this technique, start narrating how you imagine the other player to be thinking—in their own words! Literally, I’m talking about the words you think they might use when “thinking out loud.”

I moonlight as a philosopher, and my training in philosophy has taught me that “words” and “thoughts” are intertwined so tightly that they often function as the same thing. For instance, it is hard to grasp or articulate a concept for which one does not know a word.[5]Like “yomi.” So I often treat an analysis of another person’s words and thoughts as the same process.

By way of example: does this player use the word “ally” in their internal monologue? Is that the word they use to describe rival player who are cooperating with them? And if so, do they feel as though certain players are truly their “allies” and trust them accordingly? If so, this player is likely to behave in a more trusting manner than most towards their “allies”—and act exceptionally disturbed if a so-called ally takes advantage of that trust.[6]In my #3 reason why players get backstabbed post, I advised players who make this mistake too often to drop the word “ally” from their internal monologue.

In Gunboat Diplomacy, this can be extra helpful in trying to make sense of a player’s moves. Ask yourself: what does that player’s move mean? Were they thinking something like “Haha, screw you Turkey!” or something more like “Nice try, but I got you this time!”? If you can figure out how to narrate the thoughts behind a player’s decisions, you might be able to predict their future actions a little more accurately.

Step 2: Make Specific Predictions

To test the accuracy of your model, make predictions of what the other player will do. These can be predictions of how they will move their pieces, predictions of their strategic approach, or predictions of how they will react to certain developments on the board. Your goal here is to figure out if you can predict what they are doing based on your current model.

If you are familiar with my journal for The Biggest Game of All Time, you will remember that I kept a log of how accurately I was predicting each player’s moves.

I think taking the time to write down what I was thinking—to convert my vague intuition into specific predictions—forced me to be honest with myself about whether my instinctive ideas were surviving contact with reality. If you have the time, I think writing down your specific predictions is an effective way to develop this skill (as it applies to Diplomacy).

An important part of this exercise is to separate your predictions out by player. A habit I’ve noticed among inexperienced Diplomacy players is assessing each of their turns as “successful” or “unsuccessful” in an overall way (based on whether the turn worked out in their favor or not). Then they decide to “keep it up” if it’s going well, or to “change it up” if things aren’t. This not a mentally-disciplined way to approach a game for many reasons, but one of the major deficits is that this way of thinking does not break down by opponent whether you understand that particular player (or not). If you make the effort to separate out the players as individuals, you will get much better insight into how or why you are seeing the results you are seeing (and where you might do better on the next turn!).

Examples of How Thoughts Predict Actions

Without exchanging one word of press, without seeing any moves, I can tell you a lot about how a typical Diplomacy player thinks and how this results in them choosing moves:

- They value supply centers over positions. Therefore, they are unlikely to risk losing or forgo attacking a supply center in order to get units into non-supply-center positions.

- They fear losing a center more than they covet gaining one. Therefore, they are unlikely to risk losing supply centers they own to capture a new center.

- They lose interest in the match when they have performed poorly. Therefore, a player who is performing poorly is likely to make repetitive (or at least, obvious or unambitious) moves.

- They care more about psychologically justifying their choices than about winning. Therefore, they will choose moves that appear (facially) reasonable, obvious, “optimal,”[7]”Optimal” is a term of art in game theory that Diplomacy players remorselessly abuse. First of all, because players are trying to outguess each other, optimal play usually requires players to randomize their moves—not pick a specific, good-looking move set. Second, because the … Continue reading etc. If there is a move set that will “look dumb” if it fails, they will likely decide against doing it.

- They focus on their immediate interests. Events happening on distant areas of the board are unlikely to factor heavily into their decision-making. Therefore, they will typically prioritize a fight with a threatening neighbor over fighting a distant power—even if that power represents a greater strategic threat.

- They put little-to-no effort into yomi. Because they take minimal account of their rivals’ thinking, they make repetitive moves—sometimes even making the same moves multiple times in a row.

I could probably list three-dozen more of these mental tendencies, but I think you get the idea: the standard Diplomacy player is somewhat limited in how they think about and approach the game, both tactically and strategically. Unless I have a specific reason to anticipate that the players will be much stronger than average[8]Such as: I know the players’ identities and know they are strong players, I am in a tournament after there has already been a knockout round, or many website points are required to join the match., this is how I model each player’s mind…until I learn otherwise!

Any evidence that a player deviates from these tendencies—such as the player choosing a complicated counter-move-set—I catalogue (mentally, if I’m not keeping a journal) as a data point. Even one play that requires deep thought or previous experience proves that the player is more capable than my presumptive model. In response, I update my model for that player to account for their higher skill level in general—not just with respect to the one specific typical-player habit they deviated from!

Step 3: Refine Your Model

If your predictions for a specific player turn out to be mostly accurate for several turns, then you might have a good understanding of how that player thinks. Continue to use that model!

However, if your predictions are inaccurate—especially if they are way off the mark—then you should refine your model. What are you missing? What are you over-emphasizing? There’s room for improvement somewhere!

Your refined model should retroactively explain everything you witnessed that player do. Make an effort to understand and empathize with how that player thinks—this is not the time to complain or criticize!

I don’t understand why the Russian player moved to recapture St. Petersburg. St. Petersburg is not defensible in the long run!

Has it occurred to you that the Russian player might not know that about St. Petersburg? Is it possible for you to make sense of how your rival played the game while also believing that this rival is naive about this particular tactical fact?

Or perhaps you are the player with a limited understanding of the game. Is there something about this particular match that gives Russia a big incentive to go for St. Petersburg? What is that incentive, and how would that player have figured it out (even though you did not)?

If you genuinely do not understand what that player is doing,[9]Make sure you aren’t using the phrase “I don’t understand” to mean “I disagree.” That’s some verbal chicanery so potent that people confuse themselves with it. then put some work into understanding. In a Press game, ask around! And in a Gunboat game, take a hard look at the match with an open mind.

Once you have an idea of how to explain what that player has done, refine your model. Your refined model should be capable of explaining everything that player has done for the entire match—not just one action you mis-predicted! (So if the player has played well for the first 5 years, and then done something you consider to be a blunder, “this player is a moron!” is more likely an expression of your frustration than it is an accurate model.)

To learn other ways empathy can help you with Diplomacy, read my article 6 Ways “Nonviolent Communication” Will Improve Your Press Diplomacy.

Categorize Players into Character Archetypes

If you know the particular player you are up against (maybe you’ve played with them before), then this exercise isn’t necessary. You will do much better if you appreciate a rival player as the unique individual that they are, and then predict their actions based on that.

But assuming you don’t have much to go on (maybe the match has just started, maybe it is anonymous, maybe you are playing Gunboat), then it can help to think of players as characters. Although it might be challenging to make predictions about “NearDoWell69” or some other player you’ve never encountered before, you might find it easier to make predictions if you imagine this player as “Center-Grabbing Sam” or somesuch.

There are an infinite array of archetypal players you might imagine, so I won’t pretend I can come up with an exhaustive list. I’m giving these as examples that you might use—but you should come up with your own!

- Center-Grabbing Sam never saw a supply center they could pass up. This player loves to lunge for any supply center within his reach.

- Turtling Terry is far more concerned about losing home centers than about making captures. This player never leaves a home center undefended against a possible snipe.

- Last-War Lem will repeat the last strategy that worked when they were assigned that power, and avoid whatever strategy failed the last time they were that power.

- Indecisive Izzie makes committal moves, and then experiences “buyer’s remorse” and tries to take them back.

- Oblivious Orem never notices what is happening on the other side of the board. This player will not react to distant strategic developments.

- Chargin’ Chuck throws everything in one direction, regardless of whether that makes tactical or strategic sense.

- Puppetmaster Pat is pulling your strings, twisting your mind and smashing your dreams. This player is using words to manipulate events all over the board.

- Grandmaster Gabbie says all the right things and is beloved and trusted by all. This player anticipates everyone’s actions and counters them. The flaws in their thinking will be hard to detect or exploit.

I could spend hours coming up with character archetypes…it’s a lot of fun, actually! My goal here is not to tell you my ideas for player archetypes so that you can memorize them, but rather to give you a hint as to what your own archetypes could be like. I think this technique is effective even if you come up with the archetype for the first time during the middle of the match.

Other Diplomacy players employ this technique! Check out this video by Legendary Tactics:

Remember: your goal is to use this player archetype concept to fill in the gaps in your understanding of a particular player. It is always better to model that player’s mind based on the unique quirks of in their thought.

If you want to learn more from Your Bored Brother on making mental models, player archetypes, and predicting other players’ responses, consider listening to Episode 10 of the Diplomacy Dojo podcast, which covers many supplementary ideas on this subject.

Develop Your Yomi by Playing Gunboat Diplomacy

In Press Diplomacy, a player with a deficit in yomi can compensate with other skills—typically, communication skills such as persuasion. But in Gunboat, you cannot spy on the other players’ moves through press. You can’t trick players with messages. To play Gunboat well, you must rely on yomi.

I can hear someone saying “But BrotherBored, if I can get by in Press Diplomacy without strong yomi, then what’s the point of developing that skill?” My answer: when you are struggling to attain (or prevent) a solo win, or when you are locked in a fight to the death, press messages will often be of scant value. You might not even be talking. And if you reach that moment with weak yomi skill, some of your solo wins will slip through your fingers.

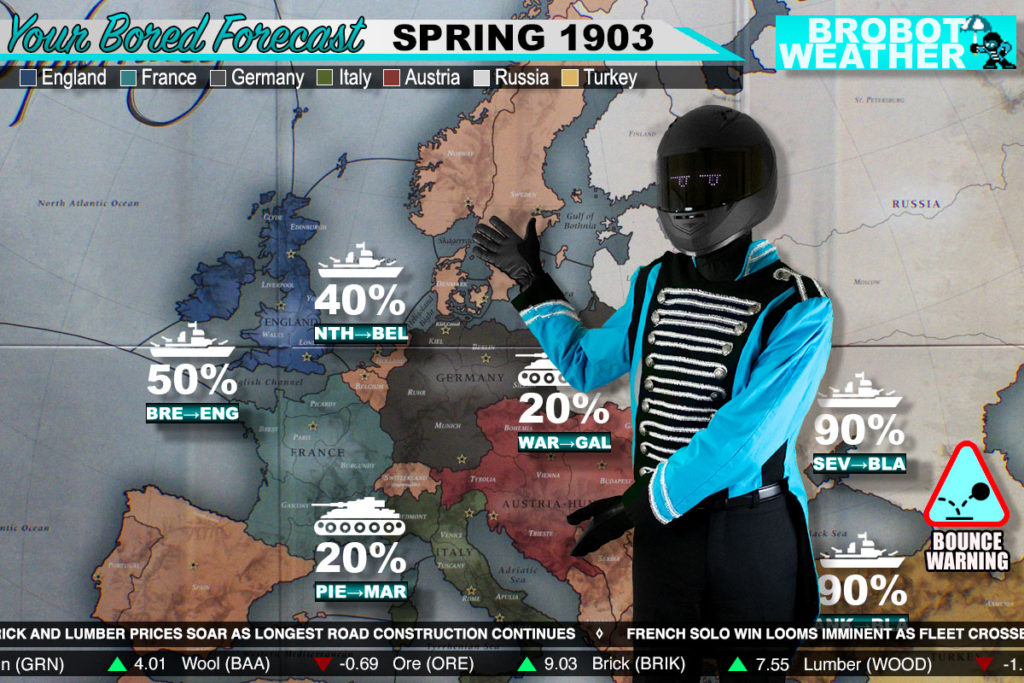

Gunboat Diplomacy is Not a Crapshoot

Applying the methods I described earlier in this article, I can predict most of my rivals’ first year of moves just based on how players typically play Gunboat Diplomacy. The base model doesn’t necessarily hold for all players or work forever, but every deviation from normal play tells a volume of information. This, the refinement process is quite simple. Each time a player surprises me, I change my model for that player to reflect what I have learned. By the end of 1903, I have a pretty strong sense of how each player thinks and can reliably predict most of their movements.

I’ve conversed with a lot of players who are skeptical of or even mystified by my claims. There are probably some readers who—reading this sentence right now—think that I am fabricating or at least exaggerating these claims. To you skeptical readers, I say: do not judge the capabilities of all human beings by your own limitations. If you believe this level of skill doesn’t exist, you are unlikely to ever attain it for yourself.

To learn more about my thoughts on how Diplomacy players limit their capabilities with unconscious (yet self-imposed!) mental restrictions, read my Solo Win Tip #2: There’s No Such Thing as Luck.

Much of the gameplay of Gunboat Diplomacy is not visible, because it is psychological. The skill of yomi will give you insight that lets you perceive this psychological gameplay.

Consult with Other Players

Analyzing your Gunboat matches by yourself is not the most effective way to improve your yomi skill. When you are by yourself, especially as a beginner, your inferences regarding other players’ moves (and the psychology that underlies those moves) will often be inaccurate. I think these misunderstandings are why some players, even after playing many Gunboat matches, conclude that the variant is mostly “luck.” Therefore, I recommend consulting with experienced players to make sure you are drawing reasonable inferences from your experiences.[10]By the way, all my Patreon Patrons get automatic invites to my Discord server, which includes the Diplomacy Dojo. I even offer one-on-one tutoring sessions as a benefit to high-tier Patrons!

I also recommend talking to other Diplomacy players just to learn how they think. I believe I have a huge advantage in my yomi ability with respect to Diplomacy because I have interviewed many players in post-game discussions, coached a lot of players (rookies, intermediate, and even other expert players), and I keep up with Diplomacy publications and interviews. This gives me a huge base of knowledge to draw upon when analyzing the psychology of my rivals.

An Example of Yomi in Action

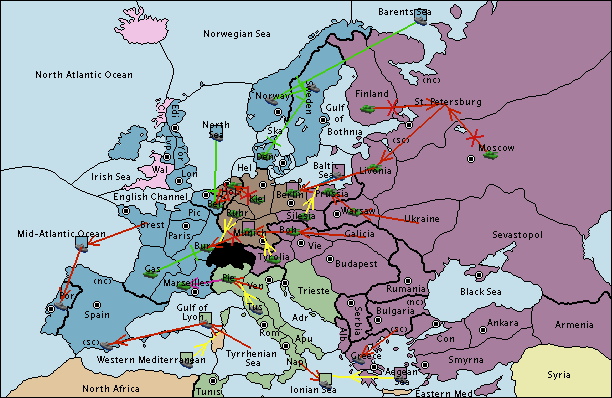

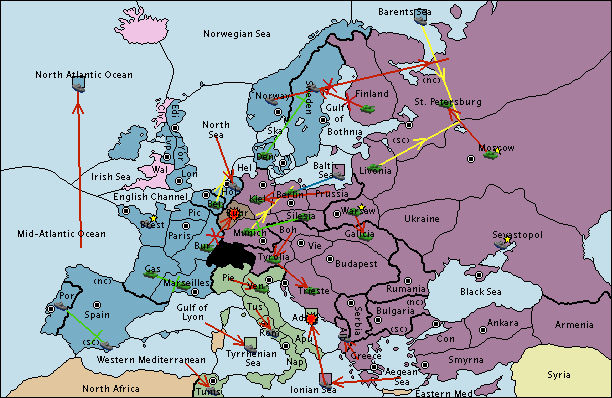

Last year, I published a two-part article on how I got a solo win as Russia in a high-level Gunboat Diplomacy game.

I felt compelled to write an article about that particular match because I had faced such immense difficulty getting solo wins as Russia in Gunboat that I started to wonder if it might not be possible (at least, in a match between strong players). However, I was able to get a solo win as Russia, and I attribute that solo win to my tremendous yomi talent. Let me set up my point with a quotation from that second entry:

As I got closer to initiating my first solo win run, I shared my turn-by-turn predictions with one of my Gunboat students who was following the match. You’ll have to take my word for it, but turn-after-turn I was making specific and accurate predictions of how the Italian player would move their pieces. I assure you, dear reader, that these were by no means easy or obvious predictions; my follow-along student found it challenging to understand my reads, because the Italian player’s thinking was just so different from how my student would have analyzed the situation (had my student been in Italy’s position).

Indeed, I would have made very different choices from the Italian as well. But my predictive mental model for a rival Diplomacy player is not “what would I do in this situation?”—it’s “what would this player do in this situation?”

The Italian player had many reasonable tactical options for how to use the fleet in Ionian Sea to interfere with my solo win run. (For example, the Italian might have moved the fleet to Eastern Mediterranean Sea in order to capture Smyrna and hold down my supply center count below 18; this is what my student said they would have done.) But my ability to read this player was just so strong. I said “The Italian is going to move the fleet to Adriatic Sea.” I felt 99% confident in this read. [. . .]A Winning Strategy for Russia in Gunboat Diplomacy, Part 2

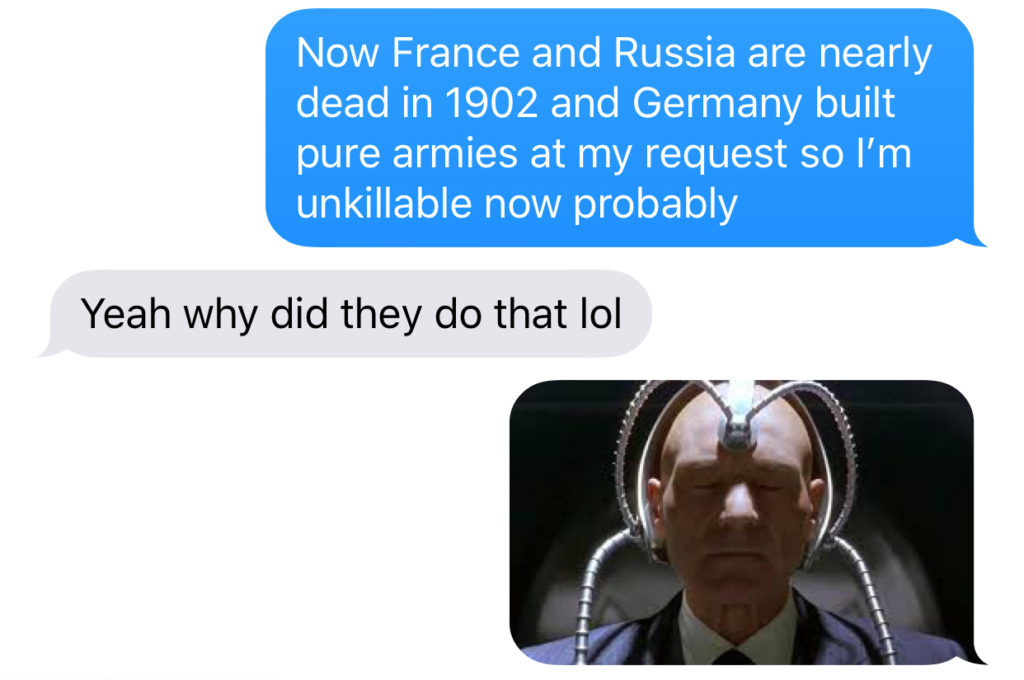

Now with that set up, I’d like to show you an excerpt from the conversation I was having with my student over Discord in real time.[11]Please bear in mind that this conversation has been edited down for focus and readability. However, the included statements are basically copy-pasted from the conversation I had with my student.

BrotherBored: I don’t have my draw vote up

Italy always moves in one direction

And I’m the only player that hasn’t entered orders. Italy entered quickly.

Quick orders =everything one direction

What do I think ION is going to do

What if I think ION is moving to ADR

I think what I want here is a really solid guess on what ION will do

Student: why?

BrotherBored: Because i can can outmaneuver the unit

Move or hold my pieces correctly

Student: if I peeked his orders and knew he put in ION -> ADR, then I’d order AEG -> ION and Gre -> Alb

as far as gambling on Ion -> Adr, if I’m in Ion and Alb, then I can protect Trieste, and prod Adr and Venice falls

while lightly threatening Nap/Tun and protecting Greece

this fails spectacularly if he goes to EMSBrotherBored: Whatever I just have to guess

And that Italy will think it is better to defend than to send a raider

And try to get ION into a defensive position or maybe even just hold

Student: I would totally send a raider

BrotherBored: This Italian player is nothing like you at all

Student: yeah

so I’d say back your reads?

Then the turn happened

Student: You read Italy perfectly

BrotherBored: How do you feel about my read on the Italian

Student: I’m very impressed

BrotherBored: Does my reasoning process make sense to you though? in the past we’ve had a lot of moments where you were baffled by how I read someone as making poor moves that I countered

Student: I don’t get it (I also haven’t been watching as closely as you)

I don’t see how you read Italy

I do see how you read that Italy would turn around

the timing on his quick orders makes sense

but I don’t see how you read Adriatic vs EMS

BrotherBored: This Italian is a simpleton.

Great alliance player. But a simpleton.

Just moves everything in one directionStudent: ah

ok, that I get

but EMS is that direction

he was willing to overextend to WMS but not EMS when it is correct?

BrotherBored: Okay but this turn, the direction is “defend myself”

Student: AHHH

moves with 1 purpose

BrotherBored: yeah maybe that’s the better way of describing my read, thank you

Student: got it, he sets a goal “my ally” “my enemy” “attack” “defend”

and does it

single-mindednessBrotherBored: Yeah that’s right

yes.

my Italian hat, for this game, is that he has one single thought and directs all pieces towards that thought

which I was describing as “one direction” but I guess that was throwing you off, because literally yes that would be east

Student: ok, that’s not an accent (hat) I’ve tried out before (at least not with that thought to it)

BrotherBored: here the direction is “into a ball” or something like that

I’m really hoping you can learn something here

because I was really confident of my reads (I was wrong on stp)

Probably >50% of my Gunboat training with this student[12]At least, up until the time we were having that conversation. We’ve moved forward since then! had been about how to form a psychological profile of a given player based on their moves. These lessons were, of course, based on my theory that once you have an accurate profile, you can often predict nearly all of a player’s moves.

In our training, we’ve called the technique of articulating another player’s private thoughts (which I described earlier in Step 1 of this article) as “speaking in their accent” or “trying on their hat.” Specifically, we have been using the technique to imagine the words that players are saying to themselves in their heads as they’re making up their mind on what to do.

If You Can Read Minds, You Can Control Minds

If you understand how a player thinks, you can predict their actions. And if you can predict their actions, you can control their actions. When you know how they will react to a certain input, you can give them that input to get the result you want.

Intriguing, is it not?

And now that I’ve tantalized your brain, here comes the sales pitch: become my Patreon Patron!

Honest-to-God, I spend 10-20 hours per week keeping up this blog and supporting the Diplomacy community. And—more truth here—I would be honored to commit even more to creating content about Diplomacy (and gaming in general!). I am at my limit as a moonlighter—I cannot do any more than I am doing without changing to a part-time day job. Wouldn’t that be awesome? I certainly think so. In the meantime, I’ve been investing my Patreon money in software, equipment, and upgrades to this website.

So if you feel like you learned something from this piece and you want to know more—maybe you want Your Bored Brother’s advice on how to use yomi not just to predict but to influence players—consider sponsoring my work on Patreon. Every dollar makes a difference.

In any case, that’s an article for another day. As the saying goes, “always leave them wanting more.”

Final Thoughts: Yomi is a General Skill

There are many general game skills. Valuation, communication, logical reasoning… the list goes on and on. I describe these as “general game skills” because the skill is transferable between different games. For example, if I learn to be a persuasive communicator by playing Mafia, I can use those skills in Diplomacy or in a debating tournament. If I learn how to count cards playing Spades, I then also know how to count cards playing Bridge.

Yomi applies to numerous games. I might go as far as to say that any game where you play against an opponent could involve yomi. Something as simple as anticipating a mistake an opponent is likely to make—and then creating a situation that will allow the opponent to make the anticipated mistake—separates masters of a game from those who are merely good. These masters have not merely mastered the game itself, but mastered their opponents’ psychology!

General game skills (like yomi) don’t just cross-apply between games; these skills are translatable into general life skills that can help in everyday situations! For example, if I learn how to keep a poker face playing Texas Hold ’em, I can probably keep a “poker face” in many other situations. If I learn to make strategic plans playing Starcraft, I might be able to make make strategic plans for running a business.

And if I learn to read the minds of Diplomacy players, I might be able to read the minds of people in many situations.

Understanding how other people think is a valuable capability for any person. Honing that understanding of other people to the point where you can specifically predict their actions is even more valuable. And at the highest level of ability, that understanding can be so powerful that you learn what will prompt other people to take actions.

Sounds kinda scary, no?

Let me put this into context though. People all over the world—marketers, politicians, psychologists, your mother—have these abilities (or at least, wish they had). I once read an evolutionary biologist’s speculation that humans might have gotten into an evolutionary feedback loop of developing greater and greater levels of intelligence in order to understand, predict, and manipulate each other.

Yomi is out there. Yomi has been and always will be part of your life. There’s no way to bottle it up.

If you want to be great at Diplomacy—if you want to get solo wins more often than you currently do—developing your skill at yomi will take you very far down that path. And as a collateral benefit, you might find yourself succeeding at life’s other endeavors more often as well!

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Examples of the “fighting game” genre include Street Fighter, Mortal Kombat, and Super Smash Bros. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | I am starting to get “Patton’d” by rival players who read my blog….that’s kind of awesome? |

| ↑3 | Do I love games that test yomi because yomi is my best skill…or did yomi become my best skill because I love and play so many games that test it? |

| ↑4 | For example, for something like 8 years I thought Munich could be stalemated from the south without Berlin…that is factually false, and not difficult to figure out. Somehow, this ridiculously wrong belief did not prevent me from playing matches well. And that’s just one example! |

| ↑5 | Like “yomi.” |

| ↑6 | In my #3 reason why players get backstabbed post, I advised players who make this mistake too often to drop the word “ally” from their internal monologue. |

| ↑7 | ”Optimal” is a term of art in game theory that Diplomacy players remorselessly abuse. First of all, because players are trying to outguess each other, optimal play usually requires players to randomize their moves—not pick a specific, good-looking move set. Second, because the totality of the diplomatic value of the different outcomes of a move set is normally impossible to determine (how can you non-arbitrarily quantify the value of confusing your opponents about your skill level or true intentions?), it is rarely possible to conclude that a specific set of moves is “optimal” in Diplomacy. And if your counterpoint about “optimal” play begins with a thought like “well, to me personally, ‘optimal’ means…” then you’re doing exactly what I’m lamenting in this footnote. “Optimal” means non-exploitable; it doesn’t mean best. |

| ↑8 | Such as: I know the players’ identities and know they are strong players, I am in a tournament after there has already been a knockout round, or many website points are required to join the match. |

| ↑9 | Make sure you aren’t using the phrase “I don’t understand” to mean “I disagree.” That’s some verbal chicanery so potent that people confuse themselves with it. |

| ↑10 | By the way, all my Patreon Patrons get automatic invites to my Discord server, which includes the Diplomacy Dojo. I even offer one-on-one tutoring sessions as a benefit to high-tier Patrons! |

| ↑11 | Please bear in mind that this conversation has been edited down for focus and readability. However, the included statements are basically copy-pasted from the conversation I had with my student. |

| ↑12 | At least, up until the time we were having that conversation. We’ve moved forward since then! |