(Yes)

It’s a well known and widely accepted fact that the Diplomacy map is unbalanced between particular countries. France and Russia are seen as the strongest countries, Italy and Austria as the weakest. There’s been much discussion as to why this might be the case.

I think it’s provably true that the map is unbalanced, both from east to west and south to north. This is an article about where the imbalances are, how they’re innate features of the game design, and what might be done about them. It’s about why Italy’s not a central power, and Russia’s not a corner power.

I want to argue that the imbalances are basically down to three factors: available neutrals, board position, and the stalemate line.

How Unbalanced Is the Map?

One way of ranking the success of different powers is by Calhamer Points. These are allocated pretty simply. If there’s a solo victory, the winner gets 100 per cent of the points. If there’s a draw, each power in that draw gets an equal share, however many centres they have. This is the system I want to use to measure relative strength.

The best data is unfortunately slightly old – an analysis on play-by-email games from 13 years ago.

It’s worth taking with a pinch of salt. It’s a large and relatively robust sample, but it’s not definitive. Other samples from other sources show different results. I’ve listed the average number of points each power gets per 100 games, according to those figures. A perfectly typical score would be ~14.3 points, so I’ve added afterwards what percentage of that score a country sees, in an average game.

| Country | AVG. Points | Performance |

|---|---|---|

| France | 17.1 | 120% |

| Russia | 15.3 | 107% |

| England | 15.2 | 106% |

| Turkey | 14.9 | 104% |

| Germany | 13.6 | 95% |

| Austria | 12.4 | 87% |

| Italy | 11.6 | 81% |

It’s worth saying that, looking at these results, the Diplomacy map is not very unbalanced. There’s a continuum of results and it is obviously possible to win with every power.

At the ends of the scale, though, there seem to be some obvious discrepancies. In particular, France gets three points for every two that Italy gets.

These results are not definitive, of course. I think these results would change if we took a sample from a metagame with more beginner players, or more expert players. Smaller metagames might see bigger imbalances favouring different countries—if there was a fashion for Austria and Italy always to ally and attack Turkey, for example.

But I’m inclined to think a sample this big, over a long period of time, is likely not a bad representation of what we might call the base strength of all powers.

Now, time for the interesting question. Why do some powers do better than others?

Centres After 1901

A major reason why some powers do better at the end of a game of Diplomacy is because they do better at the start. Diplomacy is a rich-get-richer game in which small advantages tend to multiply, so you’d expect early advantages to build.

The same data analysis helpfully gives centre counts for all powers after 1901, after most neutrals have been collected. The list is below. I’ve added in the percentage of centres each power has at that point, alongside the final figures.

It’s worth thinking of the end-of-1901 figures as the actual starting strength of the relative countries.

| Country | AvG. Points | Performance | Avg. 1901 Size | 1901 Size Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| France | 17.1 | 120% | 4.83 | 106% |

| Russia | 15.3 | 107% | 5.35 | 117% |

| England | 15.2 | 106% | 4.17 | 91% |

| Turkey | 14.9 | 104% | 4.18 | 91% |

| Germany | 13.6 | 95% | 4.93 | 108% |

| Austria | 12.4 | 87% | 4.40 | 96% |

| Italy | 11.6 | 81% | 4.15 | 91% |

So what does this data tell us? Well, there’s a bit of a pattern. Unsurprisingly, powers which have more units in the first winter tend also to get more points at the end of the game.

However three powers—England, France and Turkey—significantly outperform the other four compared to their standing in 1901. Another power, Russia, begins with a big lead, which by the end has turned into a small lead.

The four powers that do best are often described as “corner powers” and are said to share a common advantage: that they’re protected by the corners of the board.

The remaining three under-performers are the “central powers,” Austria, Germany and Italy.

If you’re a central power, the story goes, you need to get to the corner; eliminate a corner power by some point in the mid-game, and take their defensive advantage as your own.

This is not necessarily bad tactical advice when actually playing the game. But it’s not really a full description of why some powers do better than others.

That starts with the stalemate line.

North Against South?

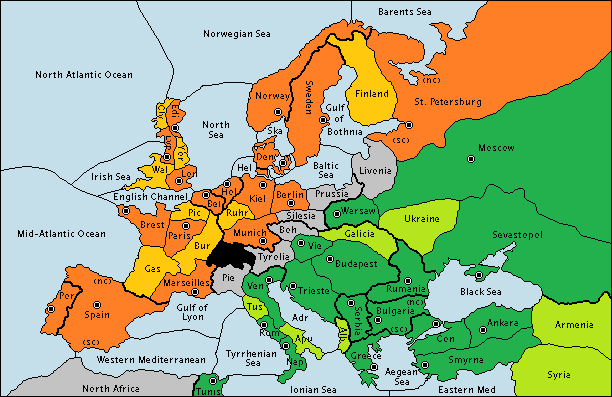

The stalemate line, as long-time Diplomacy players know well, is a group of centreless provinces running diagonally right across the middle of the board, with 17 centres on each side. Only in the top right corner, between Moscow and St Petersburg, is there no neutral barrier. At the other end, in the western half of the Mediterranean, the line grows to double thickness, with the Tyrrhenian Sea, as well as the Western Mediterranean and Gulf of Lyon, acting as a barrier.

The line is a very substantial game feature—surprisingly so, given that many people play for years without knowing it exists. It acts as a powerful constraint on conflict. Only Russia, which starts with centres on both sides, crosses it regularly.

Victory requires 18 centres, so you’ll need to cross it at some stage to win. But any winning power, other than Russia, will usually control around 14-16 centres on its own side of the line, and just 2-4 on the other side. All powers except Russia are more likely to control the most distant centres on the near side of the line than the closest centres on the other side. France is more likely to take St Petersburg than Rome or Venice, for example. Austria is more likely to take Constantinople than Munich.

Powers south of the line tend to occupy slightly more provinces on the far side at the time of victory, but the difference is less than one centre a game.

The stalemate line is also effectively a mirror. There’s one power bisecting the line, with a foot in both spheres (Russia). There are two corner powers with aggressive relationships with Russia (England and Turkey), two central powers with defensive relationships with Russia (Austria and Germany), and two other powers which don’t touch Russia (France and Italy).

But it’s a warped mirror, because Russia has three centres in the south (Warsaw, Moscow and Sevastopol) and only in the north (St Petersburg).

Now, here’s the crux of the issue: at the start of the game, available resources aren’t equally distributed on either side of the stalemate line. Because Russia is primarily a southern power, the game starts with ten units in the north, contesting for seven neutrals, compared to twelve units in the south, contesting for five neutrals.

This means southern powers are comparatively starved of neutral centres to allow them to grow easily, while northern powers are competing for a comparatively generous supply.

You would expect this imbalance to show up in the results, and indeed it does. The three exclusively northern powers—England, France and Germany—take home just under 46 Calhamer Points out of every 100. The three southern powers get just under 39. That’s an 18 per cent premium for the northern trio.

The Impact of Asymmetry

Try this experiment in your head: Imagine that Russia was to shift around roughly ten or 15 degrees anti-clockwise at the top of the board, so that, instead of being mostly to the south of the stalemate line, it suddenly sat astride it, with two centres on either side. Russia’s shift north would pop out a neutral centre—let’s say Denmark for the sake of argument—because both sides of the stalemate line need 17 centres. Moscow’s sudden absence leaves a space in the south, and whoosh! A new neutral centre, full of surprised flaxen-haired social democrats, lands with a splash in the Ionian Sea, somewhere near Tunis.

Suddenly, the board is basically symmetrical. Russia is now a balanced power, fighting equally in north and south. The two central powers in Germany and Austria are now suddenly equally menaced by the Russian bear. And Italy, rubbing its hands with glee at the imminent conquest of New Denmark, looks almost identical to France—a Mediterranean power with two easy neutrals all to itself in the south west corner. England and Turkey, the Wicked Witches of the East and West, remain essentially unchanged.

It would be quite a dull board, because symmetry makes for very boring Diplomacy. But it would be a very fair one.

Okay, enough of that. Now squash Russia back into the south, and slot our geographically discombobulated Danes back into their proper place, and you can see why Italy and Austria, the weak sisters, are such troublesome powers. They were supposed to function like France and Germany, but Russia squeezed in next to them south of the line, like an extra rugby player getting into the back of a taxi, and there wasn’t enough room to go round.

Austria and Germany

The easiest place to see the impact of this is by comparing Austria and Germany, which are clearly fraternal twins. Both have almost identical board positions and similar access to neutrals. The only difference is Russia.

Germany has a strongly antagonistic relationship with England and France, but only a weakly antagonistic relationship with Russia (which rarely attacks Germany before the mid-game).

Austria, on the other hand, has a strongly antagonistic relationship with Italy and Turkey, but also a strongly antagonistic relationship with Russia (which is crammed in right beside Austria, and often attacks in 1901). Austria often struggles to fend off and deflect all these potential enemies. As a result, there’s a one-in-three chance that Austria’s lost a home centre by the end of 1902, and a not-insignificant chance that it will be out of the game altogether. While Germany gets eliminated from just under half of all games, Austria gets eliminated from almost two thirds.

The results show up clearly in the points tallies, too, with Austria picking up only nine points for every ten that Germany manages.

France and Italy

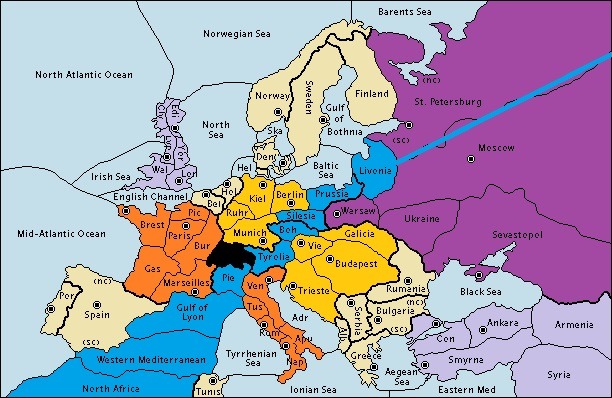

Okay, now let’s look again at France and Italy—often seen as the board’s strongest and weakest powers respectively—through the same lens. We can begin to see that the difference between them has got nothing to do with their position on the board. In fact, we can see that this idea of one being a centre power, and the other a corner power, is basically untrue.

Italy’s been conceptualised as a central power in large part because visually it’s in the centre of the map, whereas France is described as a corner power because it’s visually at the edge. But this is an illusion, created by the distortion of big empty spaces in the top left and top right. If we look at an equalised depiction of inter-territory relationships, with all provinces the same size, we can see that in game terms, the two countries occupy virtually mirror spaces.

In fact, if defensive position is the key to being a corner power, Italy’s claim is probably better than France’s. The two countries’ positions are very similar; a narrow land border, with the protection of the sea on both sides. But Italy has a narrower border with Austria, which can’t really build a significant navy, and a more attenuated relationship with Turkey, which is two sea spaces away (compared to England’s one from France). Both Italy and France are vulnerable to attack from an unexpected direction by precisely one power (each other), and Italy’s ability to attack France is greater than the other way around (because it can build two fleets per turn in the Med, compared to France’s one).

The biggest difference is simply that France has room to grow, whereas Italy does not.

Italy is in a resource-poor environment because Russia’s presence south of the line has meant there isn’t room for as many neutrals as in the south. There are only five. And all the neutrals except Tunis are at the other end of the map from Italy, where Italy can’t compete for them.

In terms of board resources, Italy is France without Spain and Belgium.

If anything, Italy’s got too good a defence—so good it also has no offence. The distance from Turkey means that unless Italy forgoes Tunis, it can’t attack and take a centre from the Sultan before 1903.

It’s sometimes suggested that Italy is neither a southern nation nor a northern one, able to compete equally easily in both spheres. This clearly isn’t true, though. Italy’s kept squarely in the south by a double thickness stalemate line, as we can see from the centres Italy usually wins with.

The rare Italian soloist tends to pick up four or five centres across the stalemate line, one or two more than Germany and France, and these usually include Spain and Portugal. But this usually occurs later in the game, after Italy’s had a chance to grow stronger and France has suffered some misfortune.

It’s also sometimes suggested that Italy and Austria’s problems stem from the common border between Venice and Trieste, which is said to equally hamper both nations.

In fact, the border seems to be mostly to Italy’s advantage. It allows Italy to easily attack Austria in a search for a fifth centre, thereby transferring a significant proportion of its innate problems to its neighbour. Italy’s chances of occupying Trieste by the end of 1902 are roughly 15 per cent, and its chances of occupying any Austrian centre are more than 20 per cent. Austria, on the other hand, occupies any Italian centre just 7 per cent of the time.

The biggest part of Italy’s underperformance is simply down to one thing: an inability to get a fifth unit early on. If Italy manages to find a fifth unit by the end of 1902, anywhere south of the stalemate line, its average Calhamer Points tally at the end of the game rises to 17 out of every 100—French or Russian proportions.

In short, Italy’s sidelined by the board, turned into a scavenger nation, with limited ability to exert force anywhere, often unable to push its way into a game.

This position does yield one significant advantage, however. Because Austrian and Turkish attention is naturally focused on Russia and the juicy knot of neutral territories in the Balkans, no one ever attacks Italy on the first turn.

What are the solutions?

This is not an article about how to play Italy and Austria. But the data does suggest clear strategies for each. Basically if you’re Italy, you have one big plus (that no one will attack you) and an even bigger minus (you’re small). So you need to become a mercenary power. Austria, Russia and Turkey are all fighting. None of them can afford to attack you. All of them could do with your help. So offer your services to the highest bidder, in exchange for that fifth unit.

And if you’re Austria, the strategy is even simpler. Outbid the others and hire Italy.

England and Turkey

But hang on. If the problem is down to the lack of centres south of the stalemate line, why do only Italy and Austria struggle? Why doesn’t Turkey—the third purely southern power—suffer the same? And why does England (which ends 1901 with similar resources to Italy) begin to pull away thereafter?

In part, this is about defences.

Turkey is bristling with natural protections: a sea area it can almost never be dislodged from, plus a Thermopylae-like isthmus only one army can cross at a time. These make it hugely difficult to assault, and are usually only overcome by two powers operating in concert for a long time. Plus, it’s two sea spaces away from Italy, the only naval power capable of mounting an attack.

England, meanwhile, is on an island, and has control of the North Sea, the most powerful space on the board. This leaves it in a good position to press for both the neutral centres most often left unclaimed at the end of 1901(Sweden and Belgium), and also to raid against any weak points in the French, German and Russian defences. As a result, England has opportunities to pick up a fifth unit anywhere from Portugal to St Petersburg.

But it’s also about Russia.

If being a corner power is defined by strength and number of antagonistic relationships, Italy and France would actually have a better claim than England and Turkey. Italy and France’s relationship with each other is marginally weaker than England and Turkey’s relationships with Russia.

The difference is that position gives both England and Turkey an asymmetric relationship with Russia. Specifically, Russia cannot easily attack them early on (at least, not without help) while Russia can easily be attacked by either power.

England can muscle into St. Petersburg, while Turkey can similarly force a way into Sevastopol. These two provinces are actually more likely to be included in English and Turkish solos than they are in a Russian ones.

Recall that Russia starts the game with a big advantage in terms of units, and ends it with a small advantage in terms of points. That advantage must drain away somewhere, and it seems pretty clear that it’s going to England and Turkey.

So Turkey pulls away from Italy because Turkey can leach resources from Russia, while Italy cannot do the same with France.

England marginally outperforms France from 1902 onwards, presumably for the same reason, but France starts with a big lead, and the position to launch an early cross-channel assault on England.

Why It’s Bad to Be a Central Power

So having reassessed who is and isn’t a corner power, and what being a corner power means anyway, let’s return to the two real central powers – Austria and Germany. Is this central position bad for them?

The best control experiment is Germany and France. Both are northern powers which start equally strongly, but German players end up with 20 per cent or so less points than French ones.

Looking at data from solos, it becomes clear that “central” in this instance really means “near to Russia.”

Unlike England, which can attack Russia with fleets without being attacked back, Germany is land-based, and on Russia’s doorstep.

France is actually more likely than Germany to be attacked by the purely southern powers (Austria, Italy and Turkey). Both France and Germany are fairly equally likely to be attacked by England, and each other. But the Russian steamroller obliterates Germany on a regular basis, while nearly always leaving France untouched.

When Germany solos, on the other hand, it’s nearly always the case that Russia has done badly. Surprisingly, Russia is eliminated more often than either France or England in German solos—even if you correct for the fact that Russia gets eliminated more often anyway. Germany rarely kills off Russia alone, but nearly always crosses the stalemate line at least as far as St. Petersburg and Warsaw, and often into Moscow.

England, meanwhile, is a bit more vulnerable to Russia than France is, but a bit less vulnerable to the three purely southern powers. Overall, France and England get attacked about the same amount.

It seems clear that the prevailing orthodoxy is more or less correct here. Germany’s comparative weakness comes from the same source as Austria’s—three enemies, compared to everyone else’s two. But because Russia is less focused on Germany early on than it is on Austria, and because Germany has slightly greater access to neutrals than Austria, the trend is not as pronounced.

In short there seems to be one overriding principle for success as Germany. One way or another, don’t get attacked by Russia.

Russia: a Riddle Wrapped in a Mystery Inside an Enigma

What about Russia itself, the only power on the board with no mirror?

Over the course of this analysis, the differing success of every other power on the board has been defined largely relative to the impact of Russia. What defines Russia itself?

Essentially two unique factors: a position on both sides of the stalemate line, and an extra starting unit.

Russia’s position gives it some advantages. It can build fleets on both sides of the line, for a start, and the line cannot be used to stop Russia when Russia is close to a solo.

But overall Russia’s position is a net disadvantage. Russia is the only power whose units cannot all support one another. Alone of all powers, Russia starts out with no choice but to fight on two fronts, north and south. And Russia has antagonistic relationships with four other powers, making Russia’s position even less defensible even than Austria’s.

To compensate, though, Russia starts with the most resources.

This, then, is Russia’s game: a freewheeling win-or-bust rush to see if it can keep its head start and stay ahead of the posse, or if it will get hauled back into the pack. If Russia’s pegged back early and loses momentum, the natural disadvantages tend to tell, and Russia often sinks like a stone.

All of the above explains why Russia’s win/draw statistics look a little different from the other powers. Russia wins more solos than any other power, and more quickly too, but it also gets in fewer draws proportional to its victory rate. Alone of all powers, Russia gets less than half its Calhamer Points from draws.

Russia’s presence on two fronts also makes the game more interesting for every other power. It acts as a kind of lightning conductor, allowing events on one side of the stalemate line to affect events on the other. If Diplomacy was two separate contests in the early-to-mid games, with three powers vying for dominance in each sphere, that would be much duller. But because England is competing with Russia, and so is Turkey, even the furthest powers on the board share a common interest, and the impact of every event is felt on the other side of the line.

Russia also has the interesting ability to act as a pressure valve for the south. It can take southern resources and move them north, and tends to do so, slightly equalising the greater competition for resources in the south.

Why, though, was Russia squashed into the south in the first place? Was this a mistake? Did Allan Calhamer just not realise about this imbalance when he was building the game?

Well, maybe. But in terms of game design it’s a remarkably delicate process to balance the significant Russian natural advantages and disadvantages against one another, and still make it more or less as playable as all the other powers.

We can probably draw conclusions based on Austria. If three units plus two likely neutrals is not enough to sustain you against three first turn enemies, then four units and two likely neutrals is not going to be enough against four. So maybe the squashing of Russia into the south was necessary to help it survive.

Do the Imbalances in the Game Persist as Players Get Better?

It’s generally held that the imbalances between results for the seven powers get smaller as players get better.

This makes sense. This article has barely discussed how the game is actually played, but it’s at least as much about trust and alliances as it is about where the pieces are. Good players will spot game imbalances earlier and correct for them sooner. They are better communicators and more adept at forming alliances.

Good players given tricky countries are still more than able to overcome the natural disadvantages they face, as evidenced by the fact that one in every 22 games end in an Italian solo.

There seems to be one substantial bit of comparative evidence: we can compare the stats used throughout this analysis with another dataset based on thousands of games, drawn from webDiplomacy in 2011. The results were different in two major ways.

First, there were far fewer draws in this new dataset than our previous analysis. Second, the balance of power shifted dramatically in the south, even further away from Italy and Austria and towards Russia and Turkey. The shift was so dramatic that the latter two became the strongest powers to play, while the north was all but unchanged.

My tendency is to think that more draws are a sign of stronger play. Generally speaking, games involving more able and committed players tend to end in draws far more often.

If this is correct, then it shows the imbalance closes as performance improves, but remains quite big at the level of the typical hobby player. Perhaps it shrinks down to nothing when the players are really good. The dominance of Italy in recent tournaments suggests this may be the case.

Does the Board Need Fixing?

Two final questions springs to mind as a result of this analysis. Should we fix the board to make it fairer? And can we do so?

I’m thinking maybe, maybe not. After all, the game’s been the game for a long time. A bit late to tinker with it now. And in some ways, the imbalances between powers in a game of Diplomacy make it more interesting. The differences in the board are small enough that it’s perfectly possible to win as any power, but they mean that all powers require different approaches to succeed. Since anyone who plays a lot of Diplomacy will end up spending the same amount of time as every country anyway, it all evens out. And it also means that a solo as Italy is almost impossibly satisfying.

Still, it would be nice if life with the green pieces was a little easier.

If I was to suggest a change, the answer would be to soften the southern end of the stalemate line to find Italy more resources in the north – to create an asymmetric relationship between Italy and France similar to that which both England and Turkey have with Russia.

In other words, you’d want Italy to remain focused very largely on the south, but allow it to pick up an average of one extra centre in Iberia, before 1902, in one game in every two or three, at the expense of France.

The Milan Variant

The major attempt so far is the Milan variant, which contains three main changes:

- A new inland supply centre in Milan, creating a gap between Venice and Trieste;

- The removal of Tuscany so that Rome borders the Gulf of Lyon; and

- A change at the French border so that both Burgundy and Marseilles now border Piedmont.

I can’t see how moving the centre inland helps Italy, although it certainly helps Austria. In the standard game the army in Venice is a powerful weapon to convince Austria to run a Lepanto alliance fairly. Or it can be used to stage a surprise attack on Trieste.

I also can’t see how shifting the French provinces’ borders helps anyone much. If anything, it makes it easier for the French to attack Italy, although perhaps it also allows Italy to support Germany to Burgundy.

In short, there’s only one big benefit to Italy in the Milan variant changes: Rome now borders on the Gulf of Lyon.

My instinct is that this change might be enough by itself. Rather than a whole variant, just move the edge of the Gulf of Lyon two inches south on the map, so that it borders Rome.

This would reduce the stalemate line back to its standard one-province thickness, which would be enough to allow Italy to challenge effectively for Spain and Marseilles—potentially as early as 1902, but certainly in the mid game. It would move Italy more towards what it’s often described as (a power between the spheres, capable of moving in either direction) rather than what it actually is (a power contained by the south, but isolated from its main conflicts). It would also make Rome into a useful centre, rather than the place you build when everywhere else is full.

But leaving the centre in Venice would tie Italy to the south, making sure it remained primarily in its own sphere.

Of course, narrowing the stalemate line would also make it easier for France to head east, but since Italy usually has the luxury of a couple of years without being attacked, while France usually doesn’t, it ought on balance to favour Italy.

A three quarters southern Russia and a three quarters southern Italy, plus three entirely northern powers and two entirely southern ones, would make the game perfectly balanced. And a stalemate line that was permeable at both ends would make the game more fluid and interesting, too.

Changing that one line ought to have knock on effects across the board. Any increased Italian tendency to move west ought also to strengthen Austria, which ought in turn to slightly weaken Turkey and Russia. A slightly weaker France might allow England to become the strongest power.

Who knows, though? The map’s currently delicately balanced, and it’s very hard to tell if changes would have a big impact, no impact, or the opposite impact to the one you want to have.

So Where Does That Leave Us?

Hopefully this article has demonstrated that the problems of Austria and Italy are innate issues of resources, and not just the result of poor play by inexperienced players. And also that a lot of the traditional ways of conceptualising the board don’t seem to match the actual shape.

One thing to say is that once you’re in a game, none of this is a very big deal. The trouble with writing about provinces and borders is that they start to take prominence in your mind. But in Diplomacy the disadvantages of geography are not insuperable barriers. The game is relatively very well balanced, and everyone, from the strongest power to the weakest, has plenty of opportunity.

Still, I hope I draw France next time.

If you enjoyed Dave’s article, consider reading his previous Guest Post, or listening to his vWDC Masterclass presentation!

“The best data is unfortunately slightly old – an analysis on play-by-email games from 13 years ago.”

It would be useful to know the source of this data. The meta-game exists, and can skew results.

Sure. Here you go. Josh Burton wrote a series of these analyses, drawn from PBEM.

http://uk.diplom.org/pouch/Zine/F2007R/Burton/statistician3.htm

Hi Dave,

This is a really interesting analysis of the board and of the relative strategic positions of each country. I wanted to comment on Italy, and Russia specifically.

My main comment is about the play of Italy, and the metagame that has developed over time. Your excellently identifies Italy’s positional strengths and weaknesses. However, I think Italy’s diplomatic edge has been undervalued for quite some time. I’ll start with a comparison to Russia, who I think actually much more clearly relates to Italy in an inverse way than France does. Russia is diplomatically and positionally offensive and benefits often from aggressive play that maximizes those benefits. Russia’s long term success is also influenced by the long term action on both sides of the board. Italy is diplomatically and positionally defensive, and Italy’s solo win conditions rely more on what happens in the north than Austria or Turkey, (or England/Germany/France in relation to the East) yet the main advice for Italian players involves mostly neutral or weaker offensive action and side-changing focused on the East, where it’s best partner, Russia, can easily outgain and out match Italy in the long run.

I think Italy has a distinct defensive and positional advantage diplomatically and should be exercising that power in the north from the very start, because Italy’s endgame victory requires a weakened France or Germany, who, if left unchecked, will ruin Italy’s chances early.

England/Germany will result in the quick weakening of Russia, Italy’s southern ally, and allows either Germany or England to assert itself in the med or Austria quicker than Italy.

England/France will allow France into the med before Italy is ready.

France/Germany will similarly allow both powers into Italy’s space before it is ready.

The answer? Defensive moves. Russia’s best bet is often grabbing a powerful individual ally and aggressively steamrolling forward either north or south.

Italy’s best bet, in my opinion, is to force the western powers into some sort of triple alliance.

In England/Germany, Italy should be france alligned, offering support into munich and whispering into Russia and England’s ear.

In Germany/France, Italy, should be peskily keeping France covering Marseilles and Germany covering Munich.

In France/England, Italy, should be coordinating with Germany to either attempt unorthodox moves through germany, holding a unit down in Marseilles, and sounding alarm klaxon’s to the Russian about their immanent death once germany is gone.

All these actions should either cause long enough delay, or create a western triple–which almost always breaks down in a few turns. By that time, Italy, can muster their defenses before France and Germany on the line, and coordinate a stab with England.

Just as Russia’s goal is to aggressively conquer, Italy’s real goal is to aggressively guarantee stagnation in the North.

What does Italy lose for committing two armies to defensive northern threats?

Nothing.

If Austria attacks, Italy’s position is still one of strength. An Italy biding it’s time is still effectively biding it’s time. Italy’s armies are still most often positioned to stab Austria if the time comes.

This time, as well, Russia’s strength in the south is diminished by the hungry north. Either Russia will committ more resources north, or it will have to deal with the loss of St. Pete or Warsaw to hungry England or Germany who just need that one more unit.

What do you think?

Thanks for your insightful response.

I agree about the diplomatic and positional advantages of Italy, for sure. I started to comment on it in the piece, but I stopped because I could have written a whole treatise on why the positional structures make Italy so interesting to play, and the article is already very long.

I agree with you that Italy has an edge, but I’m not sure I think Italy’s position is necessarily defensive, so much as responsive – although that might just be semantics and we’re actually saying the same thing.

Italy’s position as the only power rarely attacked in 1901 gives it huge flexibility to spot the cracks and exploit them. I totally agree that’s in contrast with Russia, whose forces are all up in everyone’s business, right from the start, and who therefore has to be proactive and drive what happens. As characterised in the piece above, which shows everyone else responding to what happens in Russia.

The reactiveness of Italy has led to various novel Italian approaches. Brother Bored recommends setting up an early raider on the Tyrolian staircase. Others suggest a waiting game. I’ve advocated an approach where you go to every other power and offer a “give-me-the-fifth-unit” alliance. All of those can work because, as you say, Italy has a couple of years to just give things a whirl and force its way into the game.

That means that your approach of pushing early in the north can also have good results.

I think you’re right that Italy wants stalemate in the north. I actually think Austria, Italy and Turkey all want that. I wrote another piece, also looking at the same data:

https://brotherbored.com/guest-post-who-do-you-need-to-kill/

It shows that all southern powers solo best if all three northern powers survive, and seems to suggest that keeping Germany going is particularly importantly Italy.

The difference is that Italy is a Mediterranean power, and usually solos with Marseilles, Spain and Portugal, so you want to (and are more likely to be able to) allocate more resources to affect the north more directly, early in the game.

I am convinced you are correct that keeping France weak is really important. I’m not so sure I agree about a weak Germany, because German success usually keeps all the boats centred around the North Sea, where you want them. I definitely agree that you want to actively play the northern powers against each other to prevent one achieving dominance.

I don’t know I would always work with France during an E/G. That would depend on whether I thought I could take and hold at least one or two northern centres myself.

I guess I’d finish with the usual caveat which is that this game is really about the people and personalities and therefore anything I had planned would totally depend on the skill and the mentality of the people I was playing with. So everything above could, in many circumstances, be wrong.