A version of this article first appeared with The Diplomacy Briefing, a weekly email for those who love the board game Diplomacy.

Advanced Diplomacy Maneuvers

After 8 years of playing Diplomacy, it’s rare for me to learn new tricks or moves. The map is finite, and after a while the surprises are few and far between. Nevertheless, I decided to dive in and look at the tricks deep under the surface.

In this article I will discuss the most advanced Diplomacy tactics. These are useful in getting ahead of the competition, and some are just plain fun to pull off!

So without further ado, let’s pull these hidden treasures to the surface…

Section 1: Uncommon Rules Situations

The Beleaguered Garrison Rule

If a unit is attacked from both sides with equal force, then that unit cannot be dislodged (even if that unit would be dislodged by either attack alone). In other words, equally-supported movements into the same province will fail regardless of whether that province is empty or occupied.

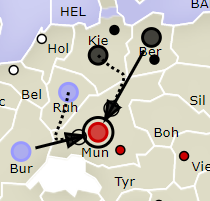

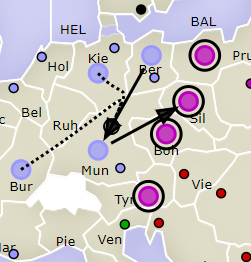

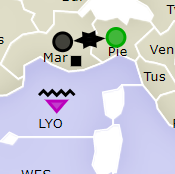

In this scenario, both France and Russia attack Munich…and both fail due to the equal strength attack ultimately bouncing (leaving the Austrian unit not dislodged).

Fleet Support for Bicoastal Provinces

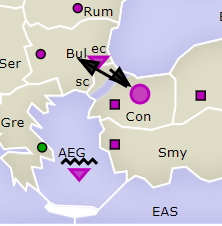

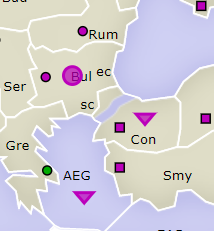

Many players are confused about how the rules apply to the three provinces with separate coastlines (Spain, St. Petersburg, and Bulgaria). In particular, players often misunderstand how neighboring fleets can issue supports to these spaces.

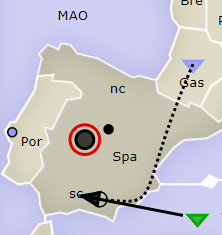

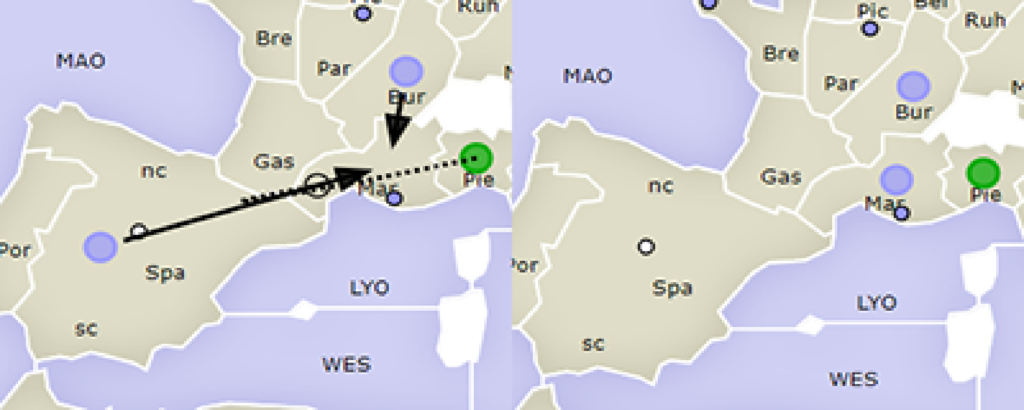

The rule is that if a fleet can move into one coast of a province, then it can support any action in that province (regardless of coast). For instance, a fleet in Marseilles can support a fleet in Gascony to move to Spain (nc), even though the fleet in Marseilles cannot itself move to Spain (nc). The fleet in Marseilles can move to Spain, and that is sufficient. Similarly, a fleet in Livonia can support hold a fleet in Saint Petersburg (nc).

Trading Places Convoy (The Loop)

Two units can exchange spaces if either or both are convoyed.

This is the only way two units can trade places.

Redundant Convoy Routes

An army using redundant convoy route reaches its destination as long as at least one convoy route remains open. There is no requirement that a player indicate which convoy route the army will use.

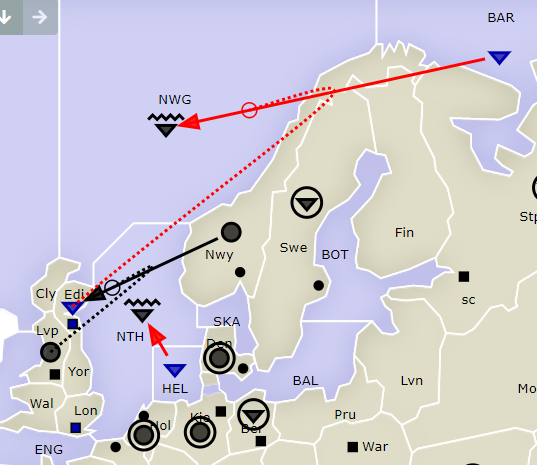

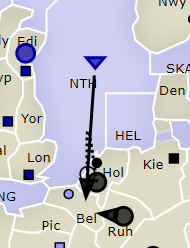

In this example, Germany really wants to convoy an army into Edinburgh…but faces a risk of England dislodging one of the German fleets. To ensure the convoy succeeds, Germany sends the army via both convoys. If either fleet is dislodged, the other will still succeed.

In this particular example, the successful convoy cut the support order coming from Edinburgh—so neither fleet was ultimately dislodged!

Part 2: Complex Defensive Tactics

Self-Standoff

A player can create their own “standoff” (a.k.a. a bounce) by ordering two equally-supported attacks on the same province. A player might do this to maintain control of three provinces with two units, especially if the player does not want to move units out of tactical positions. The self-standoff also allows a player to defend a home center while also leaving it open for a build.

In this scenario, France predictably self-bounces in Marseilles in order to capture Spain, protect Marseilles, and leave Marseilles open for a build.

Defense by 1,000 Support Cuts

If a center is at risk of supported attack, but the defender is not certain about which enemy unit will issue the support order, then strong defense tactic is to cut all possible supports to ensure that all possible attacks fail.

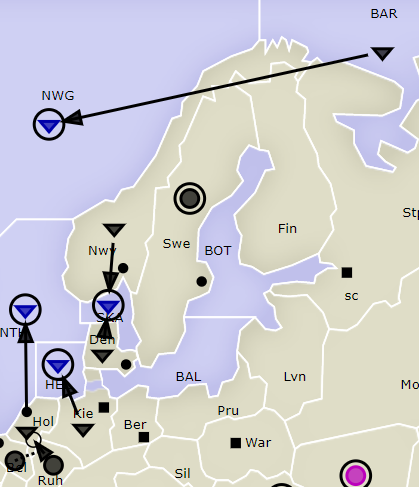

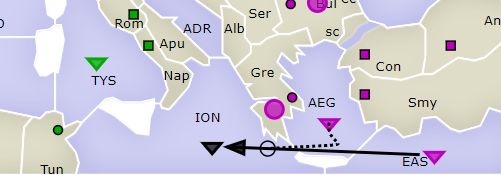

In this example, Norway and Denmark are both at risk of a double-supported attack with only enough defensive support available to fully defend one of them with support holds. Rather than leave the outcome to chance, Germany cuts support of all the enemy fleets here. This neutralizes all possible attacks. In particular, Skagerrak gets a redundant support cut from both sides to ensure it can’t support a move into either Norway or Denmark (see next section, “Redundant Support Cuts”).

Redundant Support Cuts

This is useful in situations where the defender must guess which of two adjacent provinces an enemy is planning to attack, or when the defender’s support hold orders are at risk of getting cut. Often the attacker will use the middle unit as the supporting unit in order to maintain an undisrupted front line as they push forward (see next section, “Beleaguered Garrison Rule Exploit”). To counter this, the defender uses two units to hit that middle attacker unit so that the attacker is unable to support attacks against either defending unit. Everybody bounces.

This defensive tactic is a gamble. If the attacking player supports that middle unit into one of the provinces, this maneuver could end up inadvertently costing the defender both provinces. So if you are considering this tactic, take a moment to analyze the mind of the particular opponent you are dealing with before taking the risk.

Beleaguered Garrison Rule Exploit

This tactic is quite powerful when multiple provinces are at risk.

First, the defending player moves one threatened unit to cut a potential support order from an enemy unit that is likely to issue a support. Then, supported by as many other units as necessary, the defending player moves a threatened unit sideways to the other occupied province that is threatened with attack (the same province the first moving unit moves out of). By doing this, the player simultaneously cuts off a likely source of support and triggers a beleaguered garrison bounce on one of the provinces that could be attacked. If this works, everything is safe and bounces back to where it started. This only fails if the player guesses wrong about which unit will issue the support order.

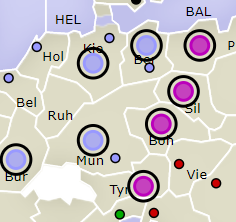

Some players mistakenly see the above situation as a coin toss where either Munich or Berlin has a 50:50 chance of being lost. However, If Silesia supports Prussia to Berlin, Munich cuts that support order and Berlin is safe. These moves protect Munich due to a Beleaguered Garrison defense. The only possible successful attack in this scenario would be Silesia to Berlin (supported by Prussia), making this defense much stronger than a “50:50” guess.

Bonus Comment from Your Bored Brother

My respected colleague VillageIdiot understates the full value of the Beleaguered Garrison Rule Exploit. I might rate this maneuver as the single-most-powerful tactic in all of Diplomacy. It true that many opponents will fail to chose the counter moves >50% of the time. But in addition to that, there are two additional reasons for why this maneuver is so powerful:

1. In many situations, the defender can’t lose.

Unless the attacker has enough units to backfill, the attacking player can only break through the defender’s defense at the cost letting one of the defender’s units break through the attacker’s line. Depending on the overall state of the board, splitting the attacker’s forces or getting behind the attacker’s line is often worth as much—OR MORE—than surrendering a province to the attacker. So even when the attacker superficially seems to “win” because they captured a center, the overall outcome may actually be a wash—or even leave the defender better off![1]To learn more , read my article about how you shouldn’t rely on just counting supply centers to estimate power.

In the above example, if Russia lacks an army to backfill Silesia, France’s army will enter Silesia as the price Russia pays for capturing Berlin. France might be able to get further behind the Russian line and wreak havoc.[2]A lone unit behind enemy lines is called a “raider,” and can be critical in attaining or stopping a solo win.

The possibility of this Pyrrhic victory is a big part of why this style of defense is so likely to succeed in the first place. If the attacker believes that losing Silesia leaves them worse off even if they take Berlin, then they won’t move Silesia to Berlin…which means they’ve ruled out doing the only attack that can succeed against this defense!

2. Often, the worst-case scenario is a future counterattack.

By dictating the exact way the attacker must move in order to succeed—specifically, forcing them to let a hostile unit through their line—the defender is well-positioned to counterattack on future turns.

In the above example, Russia can capture Berlin, but on follow up will only be able to support-hold Berlin with Prussia. France will have units in Munich, Kiel, and Silesia, thus threatening to make a supported attack the following turn that Russia can’t stop with mere support holds! Russia and France are then forced into a complex, multi-turn guessing game that could result in France later regaining Berlin without losing Munich. This counterattack also buys France time to bring in reinforcements, call on allies for aid against Russia, and so on.

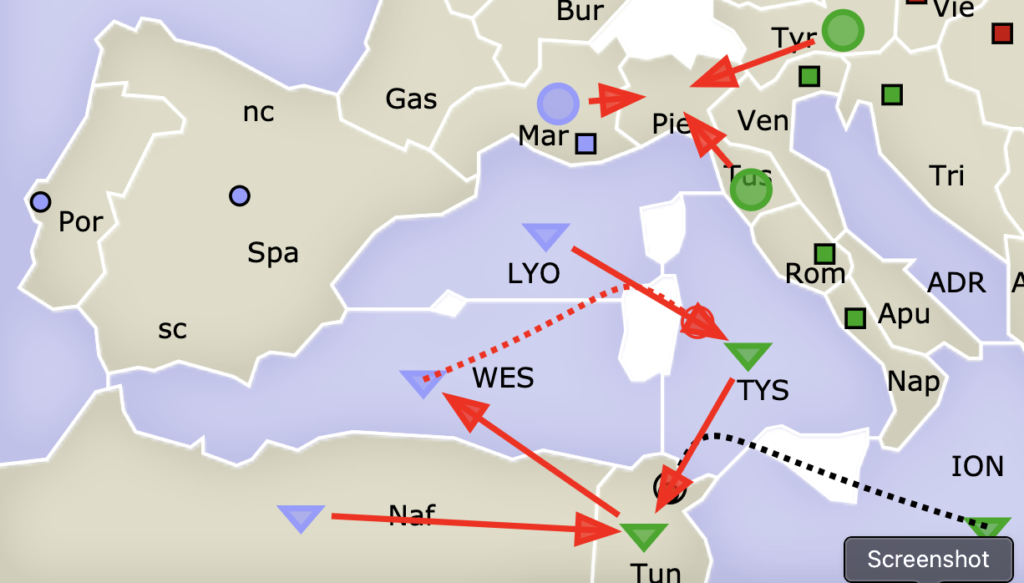

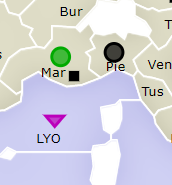

In this example, France wants to capture Tunis. However, because Italy uses the Beleaguered Garrison Rule Exploit, France has no obvious counter. Tyrrhenian Sea moves to Tunis with support, which means France cannot successfully attack Tunis. Tunis moves to Western Mediterranean Sea, which means France cannot successfully support Gulf of Lyon to Tyrrhenian Sea.

The only way France can advance is to move Western Mediterranean Sea to Tyrrhenian Sea supported by Gulf of Lyon….but issuing such an order risks Italy breaking through France’s line into Western Mediterranean Sea or North Africa. Even if France also blocks Tunis this turn, France will not have full coverage for those provinces on the next turn or a way to guarantee a capture of Tunis.

Part 3: Hostile Help

Hostile Support to Counter a Self-Standoff

A clever counter to an anticipated self-standoff is to give “hostile” support to one of the enemy unit’s moves. Supporting the opponent’s move will cause that unit to succeed in moving into the province. This is useful for pulling a unit away from its position so a different unit can walk into its former position, pulling a unit off of an unclaimed center in the Fall to prevent a capture, or pulling a unit into a home center to block a build.

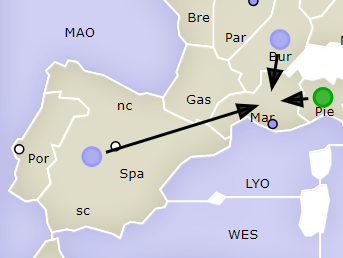

Almost the same scenario as previously illustrated for the “Self-Standoff.” However, because Italy supports Spain to Marseilles, France does not capture Spain and cannot build in Marseilles.

Hostile Support to Harass an Enemy Alliance

Sometimes, one member of an alliance will attempt to backfill (or defensively bounce) the other member’s province with no intention of actually entering the province. To interfere with their intended outcome, an enemy player can give “hostile” support to the unit moving into the ally’s space. This hostile support might force a disband of an enemy unit or cause a player to capture their ally’s home center.

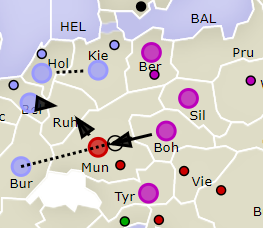

In the illustration, assume alignment between Russia and Austria. France anticipates that Bohemia will move to Munich simply to cover Munich while the army in Munich attempts to bounce a French move to Ruhr. To harass Russia and Austria, France support Bohemia’s move to Munich in order to force the disband of the Austrian army.

The Hostage Convoy

Many online adjudicators do not require the player to specify if a unit is moving via land or via convoy. What happens is the unit defaults to moving via land if possible and then attempts to convoy. The fun part is, this does not require the army owner’s permission…so if an army were to move towards another army and fail, then it would default to convoy and swap places!

Note: Not every Diplomacy adjudicator will permit this, as there are some Diplomacy sites where mode of movement (land/convoy) must be specified.

Part 4: Tactical Exploits for Allied Players

Intentional Disband

This is a clever tactic for when one ally far out of position and could really use a build back at their home centers. One ally will dislodge the other’s unit, permitting that player to disband and rebuild the dislodged unit. Opponents will often not expect this, which can turn the tide quickly as they face a surprise build!

This tactic is also useful when a player needs to change one type of unit to another. For example, in a juggernaut alliance between Turkey and Russia, Turkey might dislodge Russia’s Black Sea fleet so that Russia can rebuild that unit as a more useful army.

Intentional Retreat

This is a tactic allies can use to have the freedom to move their unit after everybody else moves first. A player will dislodge their ally’s unit so their ally can use the retreat phase to move the unit.

In this example, Germany and Russia are working together against Italy. By dislodging Germany’s unit, Germany will be able to retreat to whichever of Tunisia or Naples was not covered by Italy.

“Schizophrenic Support”

Richard Sharp shared this tactic, which is useful in enforcing agreements. The allies plan a set of moves that will only succeed if both players move as agreed. Specifically, one of the players simultaneously moves into a province while supporting the ally’s move into that same province. The supported player must move with the exact unit they agreed to move. If they don’t, the moves will bounce.

In this example, Germany agrees to allow England to have Belgium, but only if England uses a fleet. Germany supports North Sea to Belgium while also sending Ruhr to Belgium. If England uses the North Sea fleet, England will get Belgium—but if England convoys from Edinburgh, that move will bounce.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | To learn more , read my article about how you shouldn’t rely on just counting supply centers to estimate power. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A lone unit behind enemy lines is called a “raider,” and can be critical in attaining or stopping a solo win. |

Definitely a good list of some of the tactics that advanced players keep in their repertoires.

One comment about what you call the “Beleaguered Garrison Exploit”: the rule that gives this tactic its power is not the Beleaguered Garrison rule, but instead the rules prohibiting self-dislodgement. This can be a very important distinction in a real game scenario where different countries are trying to coordinate a defense.

For example, in VI’s original setup where France is trying to defend Munich and Berlin, suppose we had to change one army to a German army. If the Munich army were German, the tactic would no longer work. That’s because France hitting Munich with 2 supports would dislodge Germany in the event that the army was *not* beleaguered. When the army is French, it is the rule against self-dislodgement that prevents the Berlin army from moving by accident.

But if the Berlin army were German instead, the tactic would still work as described. The French supports would be valid for the purpose of creating a bounce but would not be allowed to cause a dislodgement.

Understanding the anti-self-dislodgement rules can be quite important when it’s not just one-on-one.