England is a power with great promise that must overcome a great problem to realize its full potential.

My Views On England Are Not Unique

Since you’re reading this article, I hope you have taken the time to check out the wonderful work of my gracious host, BrotherBored.[1]My recommendation is sincere; he is not bribing me or forcing me to make this plug. The timing of our articles is fortuitous, as he’s just finished a superb article on English gunboat strategy. You’ll notice that even though I try to be all-encompassing, our thoughts closely track each other. You don’t need to read his article to follow mine, but I strongly suggest it. You can find it in the link below.

Plug over… back to your regularly scheduled programming. England, great promise, one great problem.

The Promise: Scandinavia

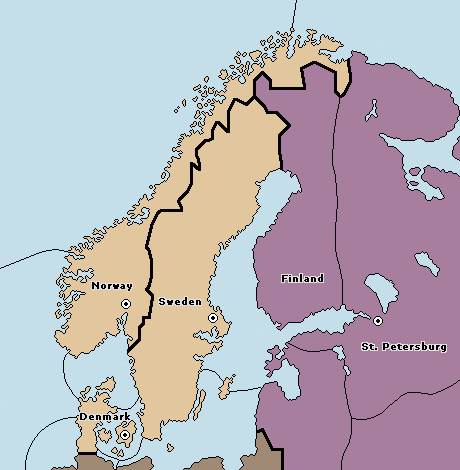

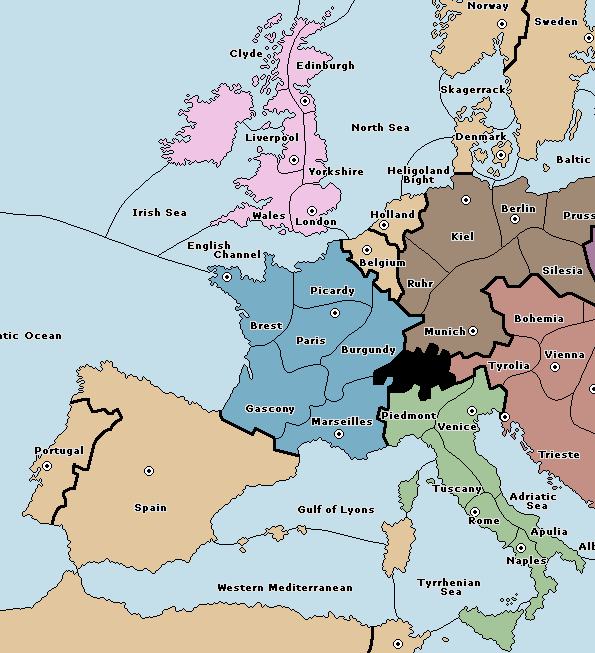

England is a naval power that starts next to Scandinavia, a four-center cluster[2]It is convention to count St. Petersburg among the “Scandinavian” centers, because the power that controls Scandinavia almost always either controls St. Petersburg or can seize it against any resistance. that is easily captured by sea and easily defended against land attacks. Scandinavia is a powerful base of operations for England. Scandinavia is only accessible by land through two land provinces, Denmark and St. Petersburg. Both provinces also project force into Kiel and Livonia. These are important launchpads for invasions inland on both halves of the stalemate line. Units occupying those spaces thus play offense and defense: they prevent enemy land invasions and they support your own.

Furthermore, England usually must occupy Baltic Sea, Heligoland Bight, and North Sea to conquer Scandinavia. Those spaces are also critical to subsequent invasions into Germany. England will often be positioned to continue a concentrated offense into Germany and Russia after securing Scandinavia. English players that conquer Scandinavia while not otherwise under duress are well on their way to a win.

The Problem: France

There’s just one problem: France. France’s best route to a solo win is to annex England and then conquer Scandinavia, just like England would. From there, France can encircle and annex Germany, and pick up Tunisia sometime along the way to get a win. France will almost always attack England first when given the choice. This plan is relatively low-risk and promises France extremely high returns.

A quirk of Atlantic sea zone design gives France the edge:

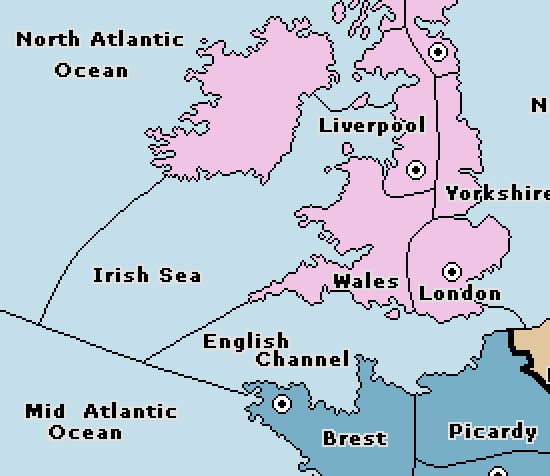

England has a home center, Liverpool, which borders two Atlantic sea spaces: North Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea. Both spaces border Mid-Atlantic Ocean. France and England, when they go to war, often skirmish indecisively over the English Channel. France thus regularly occupies Mid-Atlantic Ocean to gain leverage over the Channel. Mid-Atlantic Ocean is a bottleneck that prevents France from being outflanked from the north. If England doesn’t sneak into Mid-Atlantic Ocean immediately, England usually can’t take Mid-Atlantic Ocean until France is already beaten.

France, however, can attack Liverpool via North Atlantic Ocean or Irish Sea at virtually any point in the conflict. Fleets in North Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea only help England fight France; they don’t help England expand first, unlike French fleets in Mid-Atlantic Ocean. England must go far out of its way to place fleets there, and risk an attack from the east. England rarely bothers, which leaves France an opening. Consequently, unless England gets the jump on France, an Anglo-French war usually ends in France’s favor.

Solving the Problem: Strategies for Dealing With France

England’s foremost objective, then, is to arrange for Germany and/or Italy to bring significant pressure to bear against France. England can approach this objective in two ways. First, England can negotiate a direct military alliance with one of France’s other neighbors against France. Partitioning France between England and its ally is the objective. Second, England can also negotiate an alliance with one of France’s neighbors on false pretenses. England’s goal here is to bait France elsewhere, letting England take Scandinavia.

The former solution unambiguously involves war with France, which is difficult. But, it does promise a chance of acquiring 2-3 centers in the French sphere of influence. The latter solution forgoes (for now) the possibility of acquiring French centers. It also risks angering the power you’re baiting into the fight with France. But, it does preserve the possibility of allying with France, and it lets England secure Scandinavia quickly. How England approaches the board depends in large part on the choice of strategy.

Option One: The Genuine [War] Article

Splits land and sea with Germany;

But heightened tension on the seas

Will come from choosing Italy.

When England goes on the war path against France, Germany is by far its best ally. Although the German alliance usually comes at the cost of half of Scandinavia, this price is usually worth it. Securing England’s half of Scandinavia is easy. Securing Brest and Iberia sets England up to breach the major stalemate line in the Mediterranean. Plus, Germany is a superb complement to England as a land power. This alliance has great potential to continue deep into the game. Germany also struggles to justify fleet builds, so betrayals are easier to predict than in other alliances.

Italy, on the other hand, tends to be a liability. Possibly, Italy should be discouraged from getting involved at all. Italy tends to want the same centers England wants from France. If Italy beats you to Spain and Portugal, Italy will almost always garrison those centers. If this occurs, a middle game invasion of the Mediterranean becomes very difficult. Worse, France may prioritize its northern defenses and surrender its southern centers to Italy. This would give Italy a realistic chance of overrunning France altogether and then attacking you.

This risk is why, despite the danger France poses to England, Italy should not be the first choice for a dedicated alliance to defeat France. This is also why three-way alliances against France are usually a dicey proposition. If the diplomatic situation is strongly moving toward such an alliance, England might be better off switching to the next strategy. Leave France to Germany and Italy, and take Scandinavia for yourself.

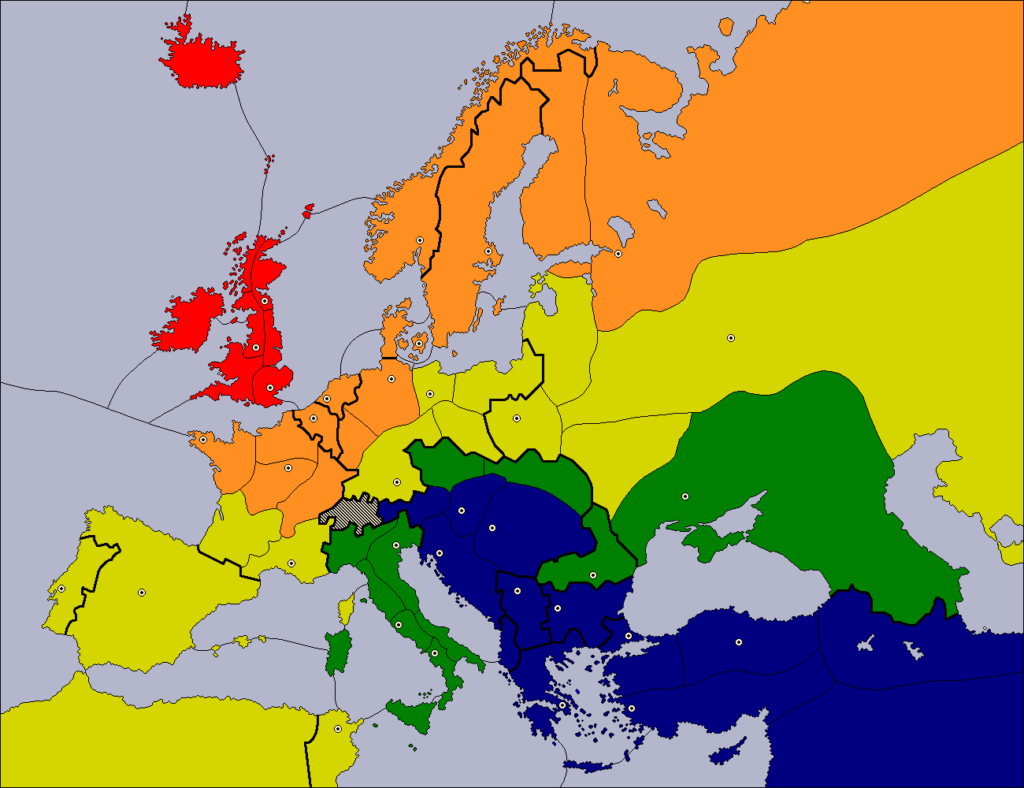

Option Two: The Phony War

However, while Italy is a dicey choice for an ally in destroying France, Italy is England’s best “decoy” option. Notice from the map posted above that France’s core territory is at the tip of the European peninsula. France is surrounded on two major fronts by water. England borders one front, Italy the other. France doesn’t border England by land at all, and borders Italy through one measly province, Piedmont. France may use its fleets to fight either power, but can only reasonably fight one at a time. If Italy attacks or menaces France early, France will be forced to send its fleets away from England to respond. This move is your opening as England to secure Scandinavia and reinforce your seas against possible future French incursions. Germany is simply less effective for this strategy because France’s fleets can’t attack Germany.

Plus, your intention to expand into Scandinavia will bring you into direct conflict with Germany. Germany has no interest in doing all the hard work against France while you pick up easier gains in Scandinavia.[3]To say nothing about the fact that you’ll likely want to take Denmark from Germany in such a situation.

Option… Three??? The Entente Cordiale

You’d be forgiven for writing off such a notion. Many veteran Diplomacy players (including me) can be very negative about the idea. The most successful Anglo-French alliances, from the English perspective, usually result from years of diplomatic wrangling. England must be wary of France’s ability to remain uncommitted in action deep into 1902. France can often justify building a fleet in Brest in Winter 1901 while being nominally allied to England to “disguise” the alliance. In reality, France is only (poorly) disguising its own treacherous intentions half the time. Many English players get blindsided by a “friendly” French fleet in Mid-Atlantic Ocean suddenly attacking Liverpool. If England, in reliance on France’s goodwill, has in the interim attacked Russia or Germany, that simple betrayal by itself can be the coup de grâce.

However, the situation changes drastically once it is France who has committed itself to war against Germany or Italy—especially Italy. This commitment can come through multiple vectors. France can earnestly negotiate an alliance with England and follow through in good faith. Italy can make a feint attack into Piedmont in Spring 1901 and provoke France to attack. Italy can make a not-so-feint attack in 1902 and demand a major response. The major principle here is that England can neutralize the danger France poses by diverting France’s attention somewhere else. This is especially true of Italy, for reasons discussed earlier. France needs several fleets in the Mediterranean to fight Italy, and a fleet in the Mediterranean is a fleet that isn’t fighting England.

There is one gambit that can make France a reliable ally… after a fight

It’s risky, but England can sometimes “take France hostage” by capturing Brest in Autumn 1901. France will only get one build; that build will often be an army in Paris to recapture Brest in 1902. England can defend Brest until Autumn 1902 and possibly into 1903. If England has successfully negotiated an alliance with Germany, then Germany should be barreling through Burgundy by this point. That incentivizes France to build another army rather than a fleet in Marseilles (which has no defensive value against Germany).

In this way, France has been induced to build only armies with its initial Iberian builds. England has thus deprived France of the ability to attack England. Now England can negotiate an alliance with France from a position of strength. This strategy is risky. You run the risk of France being angry with you and spitefully throwing centers to Germany. France may also launch futile attacks against you to “punish” your treachery. However, when executed successfully, this strategy is one of my favorites with England for one simple reason: people lie; pieces don’t.[4]BrotherBored discussed this concept at length in his Layers of Diplomacy series. If France doesn’t have the pieces to attack you, you don’t have to worry about betrayal—simple as that.

France isn’t all bad

And it isn’t as though France is fundamentally a poor ally for England. An Anglo-French alliance can easily carve up Germany, giving England a free hand to steamroll Scandinavia. This alliance is on par with the dreaded “Juggernaut”[5]An alliance between Russia and Turkey. in its board-sweeping potential. The alliance rarely lasts forever, but it accomplishes everything England wants to accomplish. You secure Scandinavia, press beyond the stalemate line, and create enough fleets to guard your flank.

What about the rest of Europe?

France’s fate will dominate England’s early negotiations. However, England needs to get on good terms with the rest of Europe, too.

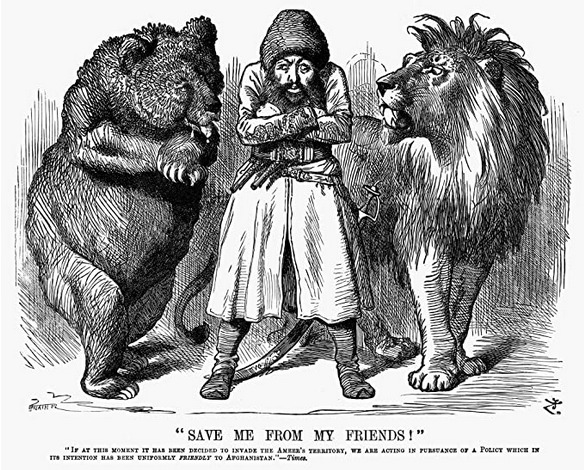

Russia: The Great Game, Continued

Russia is mostly a nuisance for England because of the inherent tension on the Norway-St. Petersburg border. Russia understandably wants Sweden, lest its northern fleet accomplish nothing. England understandably wants Norway, its natural neutral. But then there’s a foreign unit directly adjacent to an unguarded Russian home center. Russia understandably wants to use its build to protect its home center. But then there are two units adjacent to Norway, so England feels threatened. And frankly, what else is Russia going to do but take Norway?

This logic chain is far from inescapable, but it plays out in many games anyway. It will take careful negotiating to avoid the obvious battle that often plays out between England and Russia over Scandinavia. Even an Anglo-Russian invasion of Germany is usually fraught, because Germany often serves as a buffer between them. It doesn’t accomplish all that much for England and Russia long-term to ally together to destroy Germany. The same tension between Norway and St. Petersburg plays out several times over in Sweden-Denmark and Kiel-Berlin. It can be done, but it requires careful negotiating.[6]To learn more, listen to the episode of BrotherBored’s Diplomacy Dojo that discusses how to play an Anglo-Russian alliance.

And in any case, England must present a good faith argument for détente in Scandinavia if it isn’t plotting with Germany to destroy Russia, because a possible alliance between Russia and Germany is as fatal to England as an attack from France. England’s best bet is usually going to be lobbying Germany hard to bounce Sweden in Autumn 01. That leaves Russia no real option but to retreat quietly to St. Petersburg.

Austria and Turkey: Two Great Options

Austria and Turkey are too distant for direct coordination with England. In some respects, direct coordination can even be a liability. England usually needs to secure Berlin, Munich, and one or more of Tunisia, Warsaw, and Moscow to win. Those provinces are usually claimed by Austria or Turkey as part of an alliance with England against Germany or Russia. And once an eastern power has those centers, England can struggle to produce armies to take them. But Turkey’s and especially Austria’s fortunes mirror England’s, because their strength usually results in weaker games for Russia and Italy. This advantages England’s rush to crucial stalemate centers, which those powers might struggle to contest. That gives England a real chance to secure the needed centers, despite the distance.

Austria especially is a natural complement to England because Austria has such a poor naval presence; when Austria is the dominant southern power, England has very good odds of securing Marseilles, Spain, Portugal, and Tunisia. Capturing those centers gives England the inside track to a win.[7]Just be wary of Austria managing to capture Munich and Berlin! Austria is the best southern country at contesting them, and if Austria takes them, Austria can deny England a win even if England reaches Tunisia.

Turkey is even better in some respects; it’s equally distant from those Mediterranean centers as Austria,[8]However, Turkey’s only vector of attack against Italy is naval, so in practice Turkey is usually well-equipped (or at least better-equipped than Austria, by a lot) to contest the Mediterranean centers. and is much more distant from Moscow, Warsaw, Munich, and Berlin.

Opening Strategy

England has three objectives in 1901:

(1) use diplomacy or, if necessary, force of arms to keep the English Channel out of French hands;

(2) secure a build; and

(3) successfully convoy that army.

I emphasize “successfully” because the army is a major liability for England in the early game. England might as well have two units to start 1901, frankly. The army needs help to do anything productive. Part of the reason England’s starting position is so weak is that the army is an albatross around your neck. You must shepherd it across the seas to a province where it can guard a coastal supply center. Then you replace it with a unit that can actually do something.

There are a couple of positions where the army can be a great asset. These positions usually involve convoying to Picardy or Belgium as part of an all-out assault on France. However, it’s important to ensure that the convoy works. If the army ends up stuck back in Great Britain, you’re going to struggle mightily to keep pace with your rivals.

England has three good openings:

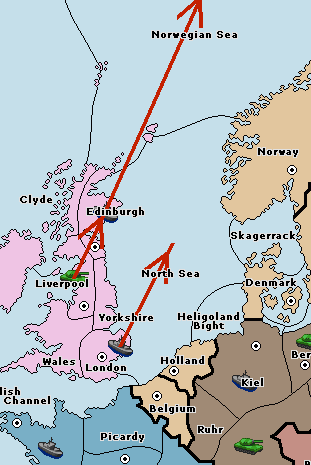

(1) The Norwegian Gambit: F Edi—NWS, F Lon—NTH, A Lvp—Edi

(2) The Channel Gambit: F Edi—NTH, F Lon—ENG, A Lvp—Edi[9]Yorkshire is equally viable to Edinburgh for this opening.

(3) The French Assault: F Edi—NTH, F Lon—ENG, A Lvp—Wal

The Norwegian Gambit: France Is Cool!

The Norwegian Gambit defers the fight against France to afford England the most options with its first year. From this position, England can continue to Barents Sea or Skagerrak and convoy to Norway; England can convoy to Belgium, or provide support for a move to Belgium while convoying to Norway; England can even bounce Denmark or Holland while convoying to Norway. If Russia moves to St. Petersburg, England can support its own convoy to Norway. This opening checks the latter two requirements most convincingly, but risks France taking the English Channel.

The big danger is that by deferring action against France, England lets France start the fight on its own terms. This opening requires heavy negotiation with France and high trust; engineering a dust-up over Piedmont or Burgundy in Spring 01 wouldn’t be the worst idea, either. This opening is very boom-or-bust (hence “gambit”) because if France decides not to attack you, this opening maximizes England’s force projection early in the game and gives England the best chance to conquer Scandinavia efficiently. But if France does attack you, you’ll be caught out of position and struggle.

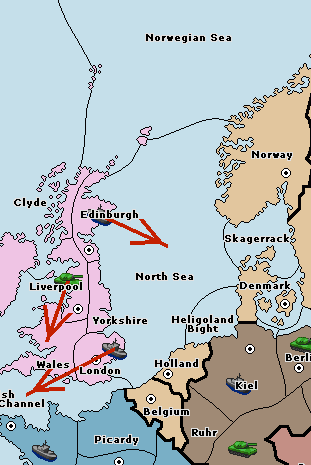

Yorkshire, And Bad Hedges

Notably, I have dispensed with the Yorkshire variant of this opening completely. (This involves moving the army to Yorkshire instead of Edinburgh.) I have dispensed with perhaps England’s most popular opening because I believe the Yorkshire variant to be a bad hedge. The theory behind the Yorkshire variant is that it guarantees you a build in the worst-case scenario: a French move to English Channel and a Russian move to St. Petersburg. The army can cover London (or possibly a threatened convoy to Wales) while the fleets take Norway despite Russian objection.

The issue behind this theory is that it doesn’t properly respect this opening as a gambit. By committing your fleets away from English Channel, you are already deciding that you trust France. You want to maximize your chances of success in a paradigm where France isn’t opening to the English Channel. Moving to Yorkshire instead of Edinburgh is an appreciable downside, because you’re forced to convoy via North Sea. That means that, to influence Belgium, you can only convoy to Belgium. You can’t offer support to Belgium while convoying to Norway.

The Yorkshire variant is worse for accomplishing our objectives

Put another way, when looking at this opening from the standpoint of our three objectives:

- Use diplomacy or, if necessary, force of arms to keep France out of the English Channel. The Yorkshire variant does nothing to satisfy this objective that the normal Norwegian Gambit doesn’t also do. It only offers the slim promise of mitigating the consequences of failing to achieve this objective.

- Secure a build. The Yorkshire variant advances this objective in one edge case where the normal Norwegian Gambit doesn’t. That’s the rare case where France moves Bre – ENG – Lon and Russia moves Mos – Stp – Nwy. These are both very uncommon moves that, if anticipated, should lead you to choose a different opening altogether.

- Successfully convoy the army. The Yorkshire variant is meaningfully worse in this respect. It reduces your flexibility in choosing how to convoy the army by forcing you to use North Sea; it also deprives you of the ability to influence Belgium beyond convoying directly there yourself.

Don’t “play it safe” with a gambit!

In my view, the Yorkshire variation is just worse. It offers a false promise of security in exchange for directly hindering one important goal for England. This opening is a gambit, and reducing its efficacy in exchange for safety misses the whole point of the opening.

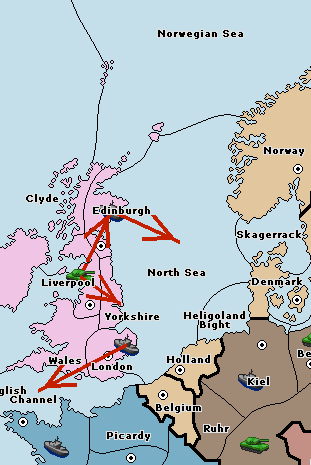

The Channel Gambit: France Is Worrisome

The Channel Gambit recognizes the threat France poses, but seeks a middle ground between the much more aggressive French Assault and the much more passive Norwegian Gambit. In the Channel Gambit, England moves to English Channel but sends the army north to be convoyed to Norway (rather than committing the army south). Perhaps calling this opening a gambit is misleading, as all told it’s a very conservative opening. It respects the power of France while still setting out to accomplish all three objectives.

It does come with a couple risks, though. While the opening guarantees the first objective is satisfied, a bounce in English Channel isn’t great either. It’s obviously better than permitting France to take the Channel, but England only meaningfully gains if the move to English Channel works.

Don’t feed the bears

The real risk is that by moving to the Channel, you risk losing Norway to Russian harassment in St. Petersburg. Still, Russia doesn’t often open north, and it’s rarely difficult to persuade Russia not to open north, given Russia’s southern priorities.[10]I advise against informing the Russian that you will be opening south, however; even though this should be welcome news to the Russian, it’s also inviting opportunistic Russian players to take advantage of you by tipping off France and opening north in the hopes of taking Norway by force in 1902. In gunboat, you don’t get the luxury of negotiation…but Russia is such a fragile gunboat power that you almost never have to worry about an army heading north, as Russia needs everything it can get down south.

Assuming you can secure the build as discussed above, the Channel Gambit lets you convoy to Norway, satisfying the third objective cleanly; the army can self-sufficiently guard Norway while your fleets take the fight to France. Overall, if the Norwegian Gambit is England’s abstractly most powerful opening, the Channel Gambit is England’s strongest opening when respecting the realities of the board. It won’t allow for the same explosive growth potential of the Norwegian Gambit, but it lets England start the fight with France on the front foot while still solving the army issue cleanly and with minimal risk of disruption.

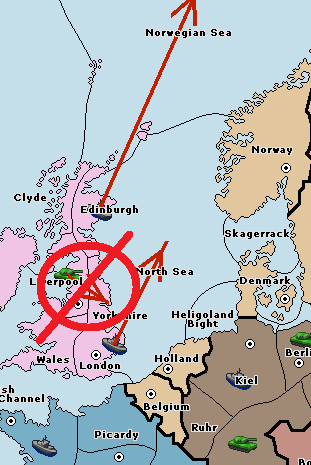

The French Assault: France Must Die!

The French Assault is the most aggressive English opening, and unambiguously seeks to resolve the problem of France’s intrinsic advantage over England by seizing the initiative with the strongest attack possible in 1901.

The opening is not without risks. The obvious risk is that if you fail, you are guaranteed not to convoy the army in 1901. The ability to convoy the army plummets after 1901, as you need all your fleets on every turn afterward. Furthermore, a sharp guess by France can still disrupt your convoy even if your move to English Channel works; France will always have a fleet guarding Brest and usually one army guarding Picardy, so you must guess where to convoy. Furthermore, this opening still has the weakness to a Russian opening to St. Petersburg discussed under the Channel Gambit. This opening does also tempt German aggression, because it telegraphs the fact that you will vacate North Sea to acquire Norway, potentially permitting a cheeky German player to move their fleet to North Sea in the fall.

Nothing ventured, nothing gained

However, this opening has one huge advantage compared to the other openings. If you can land the army in France successfully, it is much more powerful there than in any other opening. The army projects force inland against Burgundy and Paris and offers support to attacks on Brest or Belgium. The other openings understandably treat the army as a liability and mostly seek to mitigate that. This opening weaponizes the army and turns it into a real asset. It’s a very risky opening due to the drastically higher chance of failing to convoy the army, and I therefore consider it as similarly boom-or-bust as the Norwegian Gambit, but when it succeeds it puts England firmly into the driver’s seat in the west.

Tactical Considerations: Key Spaces

England’s opening negotiations tend to center on a few key spaces: English Channel, Belgium, and Sweden.

Tightrope Across the Channel

In opening negotiations, it’s probably best not to be too forthright with France about your intentions in English Channel. France makes a meaningful sacrifice in opening to the English Channel. Its fleet in Brest is the only way to capture Iberia without giving up a ton of ground to Germany. France is unlikely to make a move on English Channel if it thinks the move will fail; the tempo loss from waiting until 1903 to get a fifth unit is difficult to stomach. For that reason, you certainly don’t want to give France the impression that a move to the Channel will succeed.

Bouncing in English Channel is a problem for you as well. Although bouncing is not as bad as France taking English Channel, bouncing is worse by a significant margin than taking English Channel for yourself. So, you’d rather not agree to bounce if you can help it.

It may not be the best idea to tell France you won’t move to the Channel…but at the same time, you might not want to antagonize France by saying that you will. It’s a tough tightrope to walk, because you also don’t want to come off cagey or untrustworthy.

When in doubt, be honest

If France is pressing you for a firm answer on the English Channel, and you don’t know, don’t lie. Most French players worth their salt understand that England at least must consider opening to the Channel. The smart thing to do here is to frame the issue as one of trust, not opportunity. You’re not looking to draw first blood against France, you’re worried France might draw first blood against you. You’re concerned about things you’ve been hearing and about your own vulnerability, so you can’t commit to demilitarizing the English Channel yet. Now the conversation is about steps France can take to earn your trust. It’s much easier to continue negotiating with France if, after expressing trust concerns, you move to the Channel, than if you tell a lie[11]Boldfaced. to get in.

Belgium is (Mostly) a Trap

As England, I tend to swear off Belgium on a permanent basis, regardless of my ally. Part of this is a habit picked up from gunboat play. England has a lot of trouble picking up Belgium without using press to persuade Germany and/or France. Both powers naturally see the province as theirs, given that they need support from Belgium to attack the other. In gunboat, it’s obviously more difficult to coordinate with a third party in Belgium, even one acting in good faith.

In press, this issue is much easier to negotiate; certainly in press I would press Germany to let me have Belgium temporarily. I would try to get a fourth fleet so I could overwhelm France. (If Germany subsequently takes Belgium, you can simply scrap the army and let your fleets protect you.) But long-term, your allies will expect Belgium to be theirs, and will be in better position to protect it. It’s better to use Belgium to extract a concession elsewhere—perhaps asking Germany to give you Sweden, for instance—rather than fighting to get it for yourself. You can always convoy in when it’s time to backstab anyway, right?

Put Your Foot Down on Sweden

Speaking of Sweden, in gunboat you often have to accept that Sweden will be German for the long haul. With the benefit of press, you can pressure Germany to let you have Sweden. Generally, you should be firm about this in your negotiations. A good negotiation strategy for England is to request that Germany give you Belgium in 1901 (so that you can build an extra fleet to overpower France) and bounce Russia out of Sweden (so that one of you can claim it), then have Germany put you into Sweden in exchange for Belgium.

Don’t forget that Germany can be dangerous, too

While France is England’s overriding concern to start the game, frankly, it’s easy to get yourself in a lot of trouble by not keeping a careful eye on Germany. If you’re not aggressive in your negotiation, then Germany can easily end up with seven centers to your four and a tense but stable border with France. In such a situation, Germany has the very real option of building a third fleet, negotiating a truce with France, and beating you straight up with three fleets to your three (plus whatever help France provides).

Pushing for Sweden might rankle some German players, who generally see an even split of Scandinavia as the natural way of things. However, you have reason to be wary of a Germany that has a three-center advantage over you. Can you trust this player that much after only two game years have passed?

Your German friend should bounce Sweden for you

You should also push for Germany to bounce Russia out of Sweden in 1901. This almost goes without saying, as the question in an Anglo-German alliance is usually which of England or Germany gets Sweden—not whether Russia gets it. By extension, you should generally be alarmed if your putative German ally is set on letting Russia have Sweden. If Russia looks likely to get Romania and Germany insists that Russia should get Sweden, you should immediately be aware of the possibility of a Russian-German alliance against you. Don’t become hostile. Just point out the reality that Russia doesn’t need Sweden, and that any Russian presence in the north will greatly complicate your efforts to help Germany destroy France. And start warming up the comm channel with France, just in case.

The Road to Eighteen

England’s usual path to eighteen involves conquering France, Iberia, Germany, and Scandinavia; and then pressing into the Mediterranean to get Tunisia (most likely) or pressing into Russia to get Warsaw and/or Moscow (less likely, but still plausible).

The Anglo-German Alliance: Club Med

When allying with Germany, Tunisia is usually your most likely 18th center. The natural consequence of successfully defeating France is that you’ll have fleets hanging out around Iberia, ready to push into the Mediterranean, and largely unable to be recalled for a fight with Germany.

Warsaw and Moscow will usually be conquered by somebody in this situation. But whether it’s Germany or an eastern power, it likely won’t be you. It can be difficult to build armies to fight for those centers while also waging a decisive war against your former German ally for Munich and Berlin. Although there’s a decent chance Germany will have claimed Warsaw and Moscow by the time of your backstab (which makes those centers fair game for somebody), taking those centers for yourself is so difficult that you’re usually better off not trying.

In this situation, you probably want Turkey to emerge as the champion in southeastern Europe. It won’t be Russia or Italy if you’re playing well, and Austria is better at fighting you on the Munich-Berlin-Warsaw-Moscow axis, which will be decisive. Just be wary about an Austrian-Turkish alliance. That alliance can cut you off from pushing into the Mediterranean and pressure the German centers.

The Anglo-French Alliance: March to Moscow

Meanwhile, an alliance with France naturally lends itself to more army builds, and your logical next target after Germany will be Russia. While you should be planning to defeat France in a decisive war for your final centers, it’s very difficult to claim such a total victory that you manage to annex the French centers and Iberia and Tunisia. Realistically you will claim the Russian centers; then win a naval battle over the English Channel (whether by force or subterfuge); then conquer northern France; and finally scoop up whatever is left to get to eighteen well before you ever reach Tunisia.

Again, it’s difficult to imagine Italy or Russia doing well in such a situation, since you’ll be beating up Russia and your French ally will probably trash Italy. Turkey is likely your best counterpart again; Turkey can’t contest Munich or Berlin, and Turkey has the best chance of stalling France. Likewise, beware the Austrian-Turkish alliance.

Wrap-Up

England is a country with great potential. Exercise great care in dealing with France, land that army somewhere useful, and you will be well on your way to ruling the waves!

More from Eden’s Diplomacy Dossier:

Footnotes

| ↑1 | My recommendation is sincere; he is not bribing me or forcing me to make this plug. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | It is convention to count St. Petersburg among the “Scandinavian” centers, because the power that controls Scandinavia almost always either controls St. Petersburg or can seize it against any resistance. |

| ↑3 | To say nothing about the fact that you’ll likely want to take Denmark from Germany in such a situation. |

| ↑4 | BrotherBored discussed this concept at length in his Layers of Diplomacy series. |

| ↑5 | An alliance between Russia and Turkey. |

| ↑6 | To learn more, listen to the episode of BrotherBored’s Diplomacy Dojo that discusses how to play an Anglo-Russian alliance. |

| ↑7 | Just be wary of Austria managing to capture Munich and Berlin! Austria is the best southern country at contesting them, and if Austria takes them, Austria can deny England a win even if England reaches Tunisia. |

| ↑8 | However, Turkey’s only vector of attack against Italy is naval, so in practice Turkey is usually well-equipped (or at least better-equipped than Austria, by a lot) to contest the Mediterranean centers. |

| ↑9 | Yorkshire is equally viable to Edinburgh for this opening. |

| ↑10 | I advise against informing the Russian that you will be opening south, however; even though this should be welcome news to the Russian, it’s also inviting opportunistic Russian players to take advantage of you by tipping off France and opening north in the hopes of taking Norway by force in 1902. |

| ↑11 | Boldfaced. |

I really enjoyed this article! I can’t wait to see what you say about the other six powers.

Thanks Ahab. I got delayed by real life considerations – but keep an eye out over the next couple of days for the next installment 🙂

Eden,

At first I thought it was an excerpt from an existing book.

Now that I see your username, I realize these pieces came from your pen.

Chapeau! Especially good material!

It has now been 4 years since you wrote and posted these wonderful pieces.

Is there any chance that there will be a sequel?

I can tell you that I am not the only one eagerly awaiting that!