To teach newer players how to get a solo win in Gunboat Diplomacy games, I have created this primer and a series of strategy “cheat sheets.”

Last Major Update: August 21, 2020 (added video)

Gunboat Diplomacy is a variant of the classic board game Diplomacy. In Gunboat Diplomacy, the players may not communicate with messages. Instead, the players may only communicate with their actions (called “orders”). Since Diplomacy is primarily a game based on alliance-making and communication, the added challenge of communicating solely through the orders is an intriguing variation on the classic rules.

If you are not familiar with the mechanics of Diplomacy, this guide is not for you. If you are interested in the basics, try the help page on webDiplomacy.

My guides are intended for a player who is already familiar with the basic rules of Diplomacy (such as how the turns work and how to issue orders). I am writing for a player who has played Gunboat Diplomacy before and is seeking to achieve more of those elusive “solo wins.”

If that is your goal, then you have found the right website. I, Your Bored Brother, possess this rare combination of traits: I am a master of Gunboat Diplomacy, I love teaching others how to play games, and I have the motivation to publish my teachings on my blog. You can read more about me on my Diplomacy landing page.

In order to help inexperienced players improve their chances of getting a solo win in Gunboat Diplomacy games, I have created a series of “cheat sheets” that offer quick summaries of the strategic goals that are usually necessary to achieve a solo win for each of the 7 powers. These cheat sheets are short (around 1 page printed), do not discuss tactical minutiae (such as what order to take which centers or how to form alliances), and are not about how to play for draws. These cheat sheets are simply intended to help a newer player understand basic strategic information necessary for getting a solo win. I have written one guide for each of the seven powers.

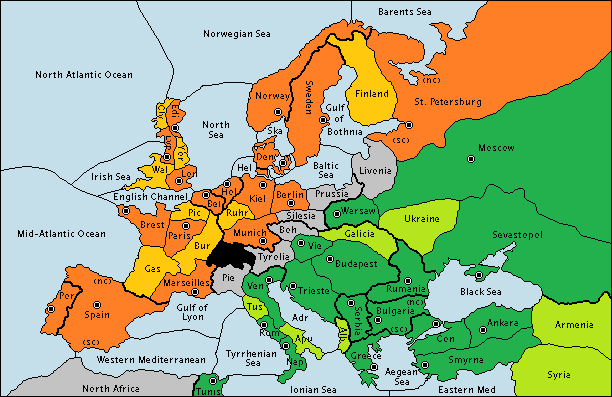

With that in mind, let me explain some general concepts that underpin all seven of these guides, together with some helpful maps. These maps are modified from the ones used on webDiplomacy.net to make them easier to look at and for me to color them.

Think of the map as two spheres: North and South

“The North” defined

- The North includes England, France, Germany, St. Petersburg (Russian), and their natural neutrals (Portugal, Spain, Belgium, Holland, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark). This adds up to 17 supply centers. Controlling all of this + 1 Southern center will win the game.

- Mostly fleets are needed to dominate the North.

- Russia is sort of a Northern power because Russia can build fleets in the North.

“The South” defined

- The South includes Turkey, Italy, Austria, Sevastopol, Warsaw and Moscow (Russian), and their natural neutrals (Tunis, Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria, and Rumania). This adds up to 17 supply centers. Controlling all of this + 1 Northern center will win the game.

- Mostly armies are needed to dominate the South.

- Russia is definitely a Southern power because most of Russia’s home centers are located there.

Why two spheres?

Once a power has conquered more than 50% of the centers in one of the spheres (usually 9 of the 17 centers), it is often easy (relatively speaking) for that power to continue on to conquer the rest of that sphere. However, a player needs to reach 18 centers to solo win and there are only 17 centers per sphere.

Reaching 18 supply centers requires a power to cross through one sphere into the other. This is relatively much more difficult than attaining 17 centers in a single sphere because there is a “no-man’s-land” running through the middle of the map. This “no-man’s land” is a line of territories running from St. Petersburg on the top right all the way down to the bottom left corner (Mid-Atlantic Ocean and North Africa) that contains zero supply centers and is tactically difficult to cross through. Furthermore, defending players hoping to stop the solo win can prevent intrusion into their sphere with as few as 13 units and will likely have several turns to get into position (as the attacker, and not the defenders, must cross “no-man’s land“).

Because of this tactical quagmire in “crossing the stalemate line” (or conversely, the ease with which defending players can rally to prevent a solo win if “the stalemate line” has not been crossed), most games of gunboat Diplomacy (and virtually all high-level games) hinge on whether or not a stalemate line is timely formed that protects the sphere of the defending players from the player attempting a solo win.

For Gunboat Diplomacy, Forget “Western Triangle” and “Eastern Triangle”

Many players will insist that the two spheres (or “triangles”) are “Western” (England, France, Germany) and “Eastern” (Austria, Turkey, Russia), with Italy straddling the middle and able to participate in either sphere. That sort of thinking makes sense for classic Diplomacy where the players can send messages, but will only confuse your strategy in Gunboat Diplomacy where the players may not message each other.

With all the authority I can muster as an expert Gunboat Diplomacy player dispensing my wisdom, I urge you to ignore the advice of people who insist on applying the “Western vs. Eastern” theory in the Gunboat Diplomacy context. I think those people are mixing up two very different games (classic and gunboat). Let me explain: in classic (a.k.a. “Press”) Diplomacy, the players are able to organize all sorts of alliances, moves, strategies, weird stalemate lines, etc. that are impossible to coordinate in a wordless gunboat game. Gunboat Diplomacy is not easier than classic Diplomacy, but it is certainly simpler.

The non-Russian powers are easily placed into 2 groups based on their solo-win plans:

- England, France, and Germany all require each others’ home centers to win and (as you will see in the individual guides I link to below) have roughly overlapping solo-win plans.

- Turkey, Austria and Italy even more so require each others’ home centers to win and have almost completely overlapping plans.

Russia is the oddball here. Russia is both a Northern and Southern power and will require significant conquests on both halves of the map in order to solo win. Do not overlook Russia‘s role as a Northern power, even though Russia only has one home center there. Russia’s ability to put fleets in the north from St. Petersburg makes Russia a part of the northern area of the board from the start of every match (Russia has one fleet to start and can build an additional fleet on the first build in 1901). Typically, Russia remains a Northern power unless and until Russia loses control of St. Petersburg.

It blows my mind that so many players insist that Italy is somehow a Western/Northern power. Sure, Italy can harass France at the start, and can reasonably take a few Southern French centers with a persistent attack, but to truly morph into a Western/Northern power, Italy must first destroy France in such a way as to continue onward to attack England and/or Germany. Pulling off that strategy with gunboat rules is extremely difficult and therefore extremely rare. Once in a while, France invades the Italian home centers, but that doesn’t cause players to describe France as a Eastern/Southern power, right?

Italy is a Southern power even when the Italian player attempts to ignore Austria and Turkey by heading West. This is because Austria and Turkey cannot reciprocate and ignore Italy. Austria and Turkey are, without exception, counting on controlling all 3 Italian home centers in order to solo win. No other powers (England, Germany, France, Russia) require even a single Italian home center to have a viable win path. (Indeed, it’s rare or almost impossible for those powers to take any Italian home centers.) Because Italy is never fully safe from Austria or Turkey while those two remain viable powers, Italy cannot fully ignore the East (that is, South) and decide to play as a Western (that is, Northern) power.

In practice, nearly all experienced players understand this. In almost every game of Gunboat Diplomacy I play, Italy begins by attacking Turkey or Austria. In the rare games where Italy does not, one of those rival powers usually just attacks Italy anyways.

Southern Victory: Munich or Marseilles is Key

Munich

Of all the supply centers located in the North, Munich is the easiest to take and hold from the South. This is because a Southern power can eventually line up enough armies behind Munich in “no-man’s land” as to make Munich very difficult to recapture from the North. Specifically, a Southern power can place armies in Tyrolia, Bohemia and Silesia to support-hold Munich. (This is not quite an unbreakable stalemate position, but this defense is usually enough to hold Munich.)

Furthermore, Munich is completely landlocked. Munich’s inland position makes that center an obvious target for Southern powers (who must build mostly armies to dominate the South) and an obvious weak point for Northern powers (who must build many fleets to dominate the North). Northern powers might not possess enough armies to defend or retake Munich from a horde of Southern armies.

Marseilles

Tactically speaking, Marseilles is much harder to acquire from the South than Munich. The difficulty is that a Northern power can defend Marseilles with relative ease against an encroaching Southern power. When a Southern power sets up a fleet at Gulf of Lyons and another unit at Piedmont, any attack made by those units can be defended by an army at Burgundy or Gascony issuing a support-hold on a defending unit at Marseilles.

To overcome such a defense, a Southern power must fight a lengthy and tactically-difficult battle for control of the spaces west of Marseilles (Spain, Mid-Atlantic Ocean, and Portugal). This battle strongly favors the defending player(s) because the area around Mid-Atlantic Ocean is a bottleneck that cannot be out-flanked or overpowered by the attacker’s committing additional units. Furthermore, a Southern power is unlikely to possess a large number of fleets and the fleets the Southern power possesses are likely not near Mid-Atlantic Ocean.

Of all the Southern powers, Italy has the strongest ability to take and hold Marseilles. Italy‘s proximity to Marseilles allows Italy to conquer Marseilles early in the match without alarming the other players. This proximity also allows Italy to build additional units that can immediately reinforce Italy‘s westward attack.

By contrast, Austria and Turkey start off far away from Marseilles. This distance means that Turkey or Austria has usually conquered nearly the entire South well before lining up units for an attack on Marseilles. Any alliance of players attempting to block an Austrian or Turkish solo win effort can easily foresee the attack on Marseilles and will line up the small number of units needed to form a stalemate position.

An Austrian conquest of Marseilles is extremely rare because Austria almost always lacks the number and placement of fleets needed to hold that position. Turkey has a better chance of conquering Marseilles because Turkey can build and position fleets more easily, and because Turkey sometimes conquers Marseilles before attempting a solo win (this most often happens if there is a Turkey/Russia alliance).

Other Centers

Rarely, a Southern power can win with Berlin or St. Petersburg. When that happens, it is usually due to a grave tactical error on the part of one or more defending players (or perhaps a player deliberately throwing the game). It is rare to win with one of these two centers because Berlin is very difficult to conquer by land from the South (and easy to retake from the North), and St. Petersburg even more so (discussed in a later section).

Northern Victory: Tunis, Warsaw and/or Moscow is Key

Tunis

Of all the supply centers located in the South, Tunis is the easiest for France or England to take and hold from the North. This is because France and England can easily send a small number of fleets to capture Tunis, and those two powers always need to build a large number of fleets anyways (fleets that, in the late-game, run out of things to do).

Furthermore, Southern powers usually build a minimal number of fleets and are typically reluctant send those fleets westward until the end of the match. If the Southern powers possess too few fleets or if those fleets are not positioned near Tunis, a Northern power can conquer Tunis and quickly incorporate that center into a defensible position.

Warsaw and/or Moscow

It is more challenging for France or England to take and hold Warsaw and/or Moscow. This is because the number of armies needed to permanently control these centers is very high, and Northern powers usually build fleets to gain mastery over the North. Nevertheless, it is possible to gain control of Warsaw and/or Moscow from the North and incorporate either or both of them into a stalemate line. England has the advantage over France in this regard because England can easily convoy armies into Norway/St. Petersburg which can then march southward into Moscow.

What about Germany?

Because Tunis is out of reach for Germany, Germany must instead conquer Warsaw to reach 18 supply centers. Germany has an immense logistical advantage in this regard: Germany can suddenly and easily strike at Russia because Germany can build new armies at Munich and Berlin. German armies are born within striking distance of Warsaw.

There’s more to how Germany is different from France and England. Germany often struggles to completely conquer the North. Germany will typically find that some portion of the Portugal-Spain-Marseilles area is beyond Germany‘s power to conquer by the time German forces reach that part of the map. Therefore, Germany‘s solo win often depends on penetrating deep into the South, conquering Moscow and sometimes even Vienna or Sevastopol to offset Germany‘s inability to conquer Iberia.

England, France, and Germany can roll up Scandinavia and St. Petersburg

St. Petersburg cannot be defended from the South against a dedicated Northern attack. There are too many territories bordering St. Petersburg to the north. Even if a Southern power has an army in Livonia, St. Petersburg, and Moscow, a Northern power can inevitably roll that defense back if that power commits enough units. For the most part, this also goes for Norway and Sweden…and even Denmark and Kiel most of the time. It is theoretically possible to set up a stalemate line that holds Scandinavia from the northeast against a southwestern invasion, but that configuration is difficult to pull off in any variant of Diplomacy and almost never happens in Gunboat. I’ve seen that stalemate line accomplished in Gunboat maybe once in my life.

Thus, once a Northern power (especially France or England ) controls everything in the North aside from Scandinavia and St. Petersburg, that power can usually also just grind down control of the rest of those centers anyways, even if the defending players put up a spirited defense.

Individual Guides

Now that you have read my general explanation for how solo wins work in gunboat Diplomacy, take a look at my guides for the individual powers: