This is the second article in a series. To read the first article, click here.

As I explained in the introduction to Layer 1: Politics, among the challenges facing new Diplomacy players is the struggle to understand what is “really happening” in a given match. Diplomacy’s gameplay is a thousand times more complex than simply determining whether someone is lying to you. So what do you do?

To help keep your thinking clear and organized, I have proposed that you should think about a match of Diplomacy in layers. Specifically, the Political Layer, the Tactical Layer, and the Strategic layer.

In my last post, I described the Political Layer. (Some people call this layer the “Diplomacy,” but that is confusing since the entire game is called Diplomacy. I’ve used the world “Politics” for clarity.) The Political Layer includes the press and the social relationships of the players. Politics is how players charm, guilt, trick and otherwise manipulate each other. I have observed players talk their way in and out of almost anything. Sometimes players seem to perform miracles through their messages.

However, even though Politics is important, and even though Politics can feel very “real,” Politics is merely the outer layer of Diplomacy. Politics is not what is “really happening” in a Diplomacy match.

To understand how to see through the manipulations in the Political Layer, we must peel back the onion to discover a deeper layer…

The Onion’s Middle: The Tactical Layer

When discussing Diplomacy, I use the word “Tactics” as a term of art to refer to how players enter orders. These Tactics include moving, holding, supporting, retreating, and building.

Although it is a reasonable use of English to refer to certain types of manipulative messages as “Tactics,” most players use the word “Tactics” to refer to the orders. In other words, when using this term to discuss Diplomacy, a player’s Tactics are defined in contradistinction to that player’s press.

I, Your Bored Brother, believe that the Tactical Layer is deeper than the Political Layer. I believe that the positions and movements of each player’s pieces tell you a truer, more accurate story about that player than what you might conclude from Politics.

Why do I say this? Because Diplomacy players are serial, even pathological liars (that is to say, some players lie so often and so habitually that they lie unnecessarily and to their detriment). Even when they tell the truth, there’s always an intention to manipulate you. Good, experienced players can manipulate their rivals with dizzying complexity. But one truth they can’t manipulate is what is actually, tangibly, on the board in front of you. If Germany’s army is in Silesia, Germany (or any other player for that matter) can concoct all sorts of reasons as to why that army is there, but Germany can’t alter the fact that the army is in Silesia.

The point of this series of articles is to equip your with mental tools that will help you see through lies, half-truths, and other manipulations. To peer through the fog of the Political Layer, what you need to do is literally observe with your eyes (or whatever method you use to ascertain the game state, if you have vision impairment). Don’t shrug off this advice as obvious, because it is definitely not obvious to many players. I believe my advice embodies a profound truth—a truth too easily forgotten during the drama of the Political Layer.

The truth is that you are playing a board game. In this board game, the players move pieces around on a map. How the players move their pieces will be completely, and utterly, dispositive of the result of that board game.

See Through Politics by Thinking Tactically

Diplomacy is similar to voting-contest games like Survivor (the U.S. television game show) or Mafia (the party game with a bazillion variants) in the sense that, in Diplomacy’s Political Layer, you are able to appeal to other players with persuasive pleas or sheer charisma (and you should definitely do this!).

But Diplomacy is not a popularity contest, and players don’t get voted out. There is a Tactically deep and interesting war of maneuver taking place at all times. Thus, one of the key tendencies of a successful Diplomacy player is that the successful player never looks away from what is tangibly taking place on the board.

This is not an article about how to make the right Tactical choices on a particular turn in a particular match. There are methods for figuring out strong Tactical choices, and I know these methods, and I will teach them to you when I find the time. But that subject is far too intricate for me to explain as a sub-point in a larger article. I will undoubtedly return to the topic of Tactics in the future. If you don’t want to miss out, consider adding your email address to my updates list:

Meanwhile, what I’m here to teach you today is how to think Tactically in order to understand what is happening in your matches.

When someone shows you who they really are (through their Tactics), believe them.

Whenever a player moves even one piece in a way you did not expect (according to your mental model of that player and their intentions that you created using the Political Layer), revise your understanding of that player’s mind to take into account the unexpected move. Devious players will find ways to confuse you about the meanings of their moves; don’t fall for these Political tricks. As the saying goes, “actions speak louder than words.”

Example #1: Apocolipstick (Feb 2018—Jan 2019)

As I described in the previous article, this match was as serious as a one-off Diplomacy game can be. Last time, I talked about how I destroyed Italy, a formidable opponent. The story of this example picks up where the last one left off: right after I captured all the Italian centers.

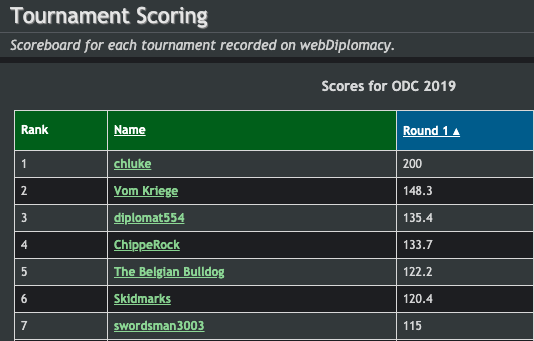

England (my ally) was helmed by the player chluke, who is among the greatest Press Diplomacy players I have ever had the pleasure of going up against. The match was not anonymous, so I knew that chluke was playing as England.

You can read more about my participation in the first round of the 2019 ODC in the journal I kept for one of my matches.

I am emphasizing the quality of the players and seriousness of the match so that my example doesn’t feel cherry-picked. I think this match is representative of Diplomacy play at a high level. And my experience in this match helped teach me the lesson that I am trying to pass on to you.

This was one of the most complex and challenging matches I have ever played, so to try to summarize the entire match is far beyond the scope of this article. However, this match was quite interesting and taught me many lessons that I’ll discuss in future posts. The important moment for this post comes on Autumn and Winter 1905.

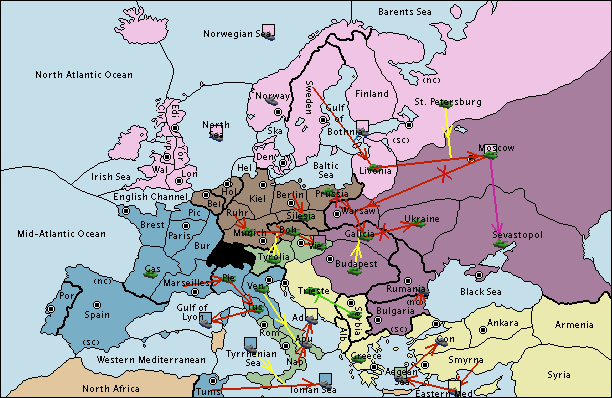

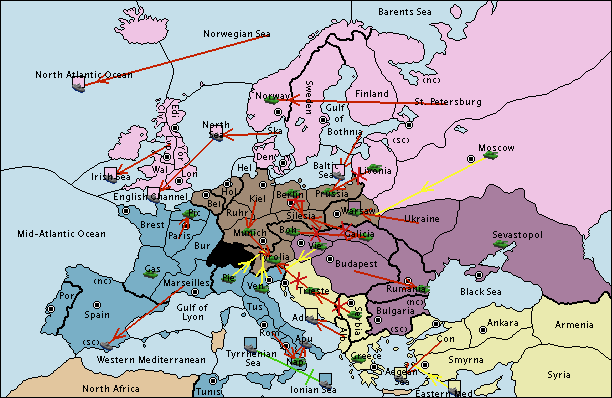

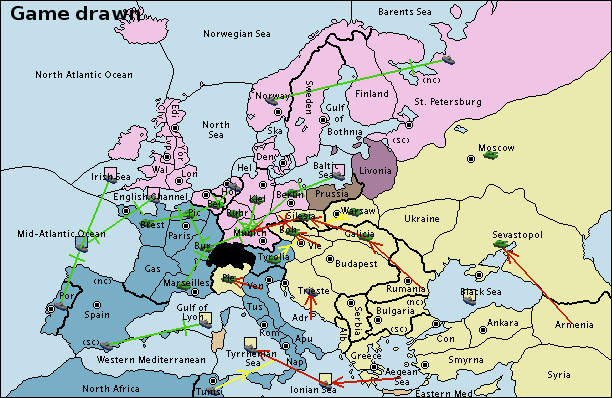

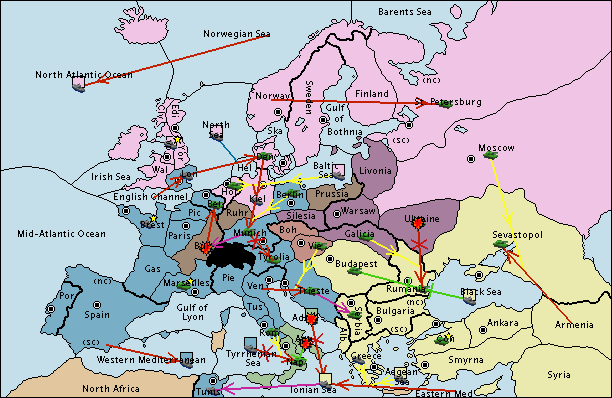

In Autumn 1905, I (France) captured Rome and Naples and had 2 builds. England captured Moscow and had 1 build. Germany captured Warsaw and had a leftover build due to voluntarily disbanding his fleet, so Germany had 2 builds.

Does that look like an army to you?

If I had been following my own advice, I would have (correctly) concluded that England had just backstabbed me, and was about to attack. But I allowed the English player to talk his way out of what his Tactical choice truly meant. He claimed that it was a misunderstanding, and that the misunderstanding was my fault—that I had not sufficiently reassured him that I would not be building a fleet at Brest. He criticized me for creating the situation, but assured me that he would, of course, not attack me (indeed, England went on to concoct an elaborate series of moves for the Western Triple to make together, but that conversation was a ruse).

The Tactical situation created by England’s build should be obvious to any player with moderate experience: It was not necessary for England to build another fleet to defend himself from a French fleet build at Brest; the English fleets at North Sea and Norwegian Sea were probably sufficient to defend against a single French fleet (or even two, if one French fleet came back out of the Mediterranean). And even if England really wanted to maximize his defensive game by building another fleet, he could have built that fleet at London (to make a supported move into English Channel and block the French fleet). But by building a fleet in Liverpool, England made it possible for him to all-out attack me the following turn by moving 3 fleets against me (Norwegian Sea to North Atlantic Ocean, Liverpool to Irish Sea, North Sea to English Channel).

Even if England was telling the truth about why he built a fleet at Liverpool (to this day, I think he lied and simply wanted to backstab the alliance), that build nevertheless created an objective situation (that is, a Tactical situation) where it was possible for England to send 3 fleets westward with no possibility that those movements could be stopped. Also, without an army to convoy, the fleets had nothing better to do. The Tactical ramifications of England’s build were enormous, and neither I nor my ally Germany treated England as a backstabber (to our detriment).

The takeaway here is that England’s decision to build a fleet at Liverpool was a Tactical choice in extreme tension with England’s stated goal of continuing Western Triple. Just looking at the map should have been sufficient for anyone to understand England’s true capabilities and hidden intentions. Of course England lied through his teeth after building the fleet in Liverpool, calling it a misunderstanding, and claimed that he would continue with the alliance—that was the perfect Political cover for his true plan of backstabbing his allies. But because the English player was a player of incredible Political skill, he manipulated his allies France and Germany into foolishly moving forward with the sham Western Triple alliance for one more turn.

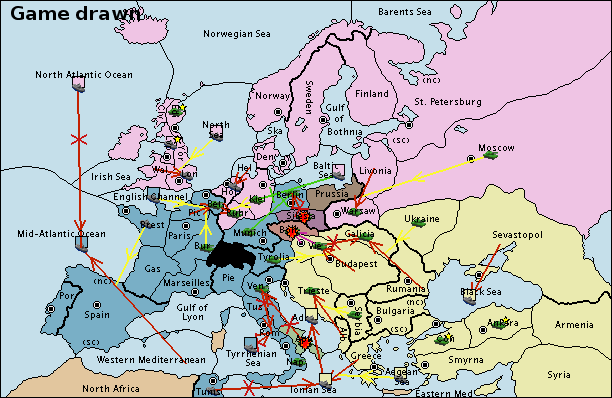

Example #2: At the Sign of the Prancing Pony (Nov 2016—Dec 2016)

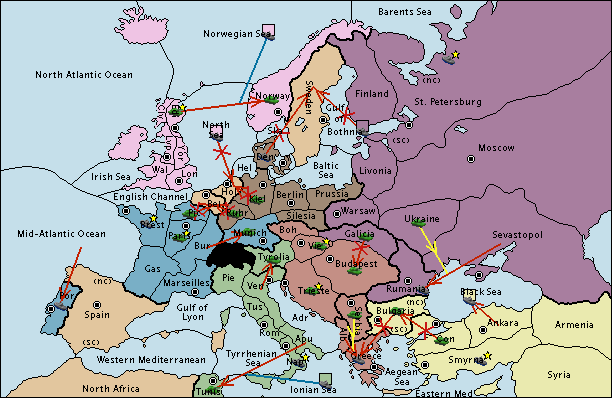

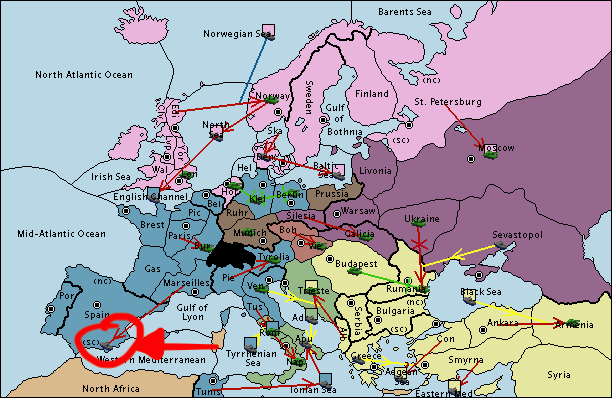

This match was not as legendary or epic as the last one I showed you (the bet was for a large-but-reachable 200 points, and the match lasted a brisk 1 month). However, I experienced a few memorable moments—including one that is relevant to this article.

Up until the Spring 1905 turn, France had told me—in advance—each move for every single one of his pieces. I found this move fairly suspicious.

France made the usual excuses:

And I initiated a detailed conversation with Turkey about how to best guard against the suspected backstab:

Note: I have chosen a few quotes for dramatic effect. My conversations with France and Turkey at this time were much more extensive than these quotes.

Anyways, what do you think happened?

I can’t help myself, so I have to say a few things in passing. There are also so many odd similarities between this medium-level match from 2016 and the high-level match from 2018-19 I discussed earlier:

- In both matches, I was allied to Tom Bombadil, a player of considerable skill and immeasurable charm (in the earlier-discussed match, Tom played Germany and was defeated. In the match I’m now discussing, Tom played as France).

- In the 2019 match, England’s tactics in Winter 1905 hinted an intention to backstab France/Germany. In this 2016 match, France’s tactics in Spring 1905 hinted at an intended backstab on England. (1905-ish is a common time for major backstabs because most early alliances have accomplished their major goals around that time.)

- In both matches, one single inconsistent Tactical choice was enough for me feel the tingle of betrayal. (What I often call my “backstab spider-sense.”)

Lessons from My War Stories

Lesson 1: When players make Tactical choices that you did not expect and do not like, get suspicious. No matter what they have said or are saying now, that player acted hostile towards you. React accordingly by taking Political and Tactical steps to protect yourself from that player’s hostility.

Lesson 2: You will have moments when you want to make a Tactical choice that is objectively hostile towards another player. Maybe you have no hostile intent…maybe you do; that makes no difference. When you are going on the offensive, apply the inverse of Lesson 1 and talk the other player into believing that you have no hostile intentions.

In passing, I can’t resist my desire to teach you how to do this. I know of three techniques. I’ll start with the best and end with the worst.

- Convince your rival, in advance, that they should approve the hostile Tactic you desire to make. Because they expect you to do the Tactic (due to their advance approval), they will not likely perceive your Tactic as hostile. A great way to convince a player is to say something like “I have to pretend like I’m hostile to you and/or that I’m going to backstab you in order to obscure the true nature of our friendship.”

Once they agree, you will be in a great situation. You can either surprise attack them from a Tactically-advantageous position, or decline to attack and perhaps gain credibility with that player. If the player won’t agree to your hostile Tactic, you can withdraw your request and act like it wasn’t important; the player may even like you more afterwards because you asked their opinion and respected their decision.

You almost can’t lose with this technique. I absolutely recommend that you use it as much as you can. I used to my tremendous advantage in the 2019 ODC, and you can read about it in my journal. - Announce your intentions, even though the other player won’t like it. If the player is in a tough situation where there’s no way they can retaliate against your move, they may simply accept what you do. In other words, this technique is best used when the other player is under attack, or simply depends on your charity or mercy in order to survive.

This technique can backfire, because giving your target advance notice of what they consider a hostile Tactic will afford them a lot of time to change their Political posture. They can use the time to recruit other players against you. Use with caution.

3. Make the moves you want to make, and then make excuses after the fact. Decent excuses include:

“Woops, that was a misorder.”

“I misunderstood what you were expecting; this is a miscommunication. I’m sorry!”

“I thought you [or someone else] were going to do something different, so I felt like I had to do this move to protect myself. I don’t mean anything by it.”

Before using this technique, I think you should have your excuse prepared in advance. If you haven’t thought through what your excuse will be, you may make the Political situation worse by offering a flimsy excuse.

Use this technique as a last resort. This is a gamble. In high-level matches, most players will see right through the excuse. And no matter what happens, you will have diminished credibility with the player you offended. Because technique 3 requires you to lie, it is worse than technique 2. Most players are offended far more by lying than by open-and-honest hostility.

Lesson 3: Watch out for players who have learned Lesson 2. Now that you have learned some of these techniques, you might notice when someone is trying to use them against you.

I hope that if you internalize these lessons, you will gain an appreciation of the bigger idea: Tactics is the deeper layer than Politics because the board is a more reliable indication of truth than words.

“Actions Speak Louder Than Words” is Applies to Diplomacy Because the Saying is a Truism for Life in General

In my essay American Minds & American Movies, I described how difficult it is to understand how another human being thinks:

To become skilled at understanding the hidden thoughts of other people [. . .] is the project of a lifetime. If you are genuinely interested in developing this skill, I highly recommend playing competitive board games like Diplomacy. Playing competitive games is a great way to develop this skill because you force yourself to think hard about the secret thoughts of other people (including people you may have never met before).

Your Bored Brother, “American Minds & American Movies” (2019)

Each person’s subjective intentions, beliefs, and thoughts are something that others can never fully discern. A person’s words are some indication of their inner thoughts, but the words are not themselves the thoughts. Even when a person is trying to be 100% honest in describing their thinking, that does not mean the person is being 100% accurate; people are motivated by thoughts and feelings that they are not aware of, that they don’t understand, or that even defy description. And some people lack all self understanding.

In addition to all the difficulties you must face when trying to understand an honest person, you will encounter people who are deliberately cryptic and even misleading about their thinking (gasp!). Combining those two problems together, I will go as far as to say that the majority of statements people make about how they think are false (that is, inaccurate on purpose or by simple mistake).

With this in mind, I don’t expect a Diplomacy player’s messages describing their thinking to be accurate.

Do You Love Me?

What if I asked you to describe, in words, why you love someone? I highly doubt you are aware of all the circumstances that led to your feeling of love (maybe you met on a scary bridge, and this made you feel attracted). Even if you are aware of many or most of your reasons, I doubt you could describe all your reasons in words in any reasonable amount of time—you would summarize, or use an example, analogy, etc. (“My world begins and ends with her!”) And even if you knew, and were capable of efficiently describing the reasons, I doubt you would be comfortable admitting the truth of many of them (“I love him because he’s just like my father.”).

And feelings of love are probably among the most important feelings people experience—they build their lives around love; they would give anything for it. People think about love all the time, but they’re not so good at articulating the feeling in words (proof by counter-example: people who can do this are mesmerizing, and may even drive witnesses to weep at the beauty of such a feat).

Golde makes it clear that the objective manifestations of her love were undeniable. She argues that if her hard work and sacrifice do not constitute love, then she doesn’t know what love means.

(Still, it is beautiful for the characters to verbalize their feelings.)

Meanwhile, you’ve got people who say they love someone all the time, and yet there’s little evidence for this. I don’t have to provide examples; you know what I’m talking about. Maybe they really are experiencing feelings of love, but lack the basic sense that should tell them the proper way to act on it—that’s possible. But probably someone who does not appear to love another person should just be disbelieved when they merely speak the words. Love can (and must!) be demonstrated through actions. What I’m really getting at here is that someone who acts in a way that is fully consistent with not loving another person probably doesn’t—and that there’s no objective difference between a person who is incapable of acting properly on feelings of love and a person who simply lacks such feelings.

So the next time you are Italy and the guy you’re dating (Turkey) tells you that he’s going to divorce his wife (Russia), but the timing just isn’t right, and so he has to keep up pretenses by building a fleet at Smyrna… maybe you should conclude that Turkey is playing games with you. (Zing!)

To Be a Great Diplomacy Player, You Must Master Tactics

As I said earlier, I don’t have room in this article to explain everything there is to know about Tactics in Diplomacy. Instead of giving specific advice, I’m going to advise you on how to train yourself to become better at Tactics.

I believe I have mastered the Tactics of Diplomacy through becoming a veteran Gunboat Diplomacy player. Gunboat Diplomacy is a rules variant of the original game where the players are not allowed to communicate in words—the players may only communicate through their moves.

Gunboat Diplomacy has its design limitations (I have previously written about how I think the game is unbalanced compared to Press Diplomacy). Gunboat Diplomacy lacks the complexity and depth of Press Diplomacy. However, I believe that Gunboat Diplomacy teaches players some basic Strategy (more on Strategy later!) and—most importantly for this conversation—forces players to learn how to think Tactically.

In Gunboat Diplomacy, you must ponder yourself the implications of every move of every piece; nobody will explain what they’re doing. You must choose your moves based on your understanding of strong Tactical choices and your intuition of what your rivals are going to choose for their moves; nobody will tell you what you should be doing, and you can’t manipulate other players with lies.

If you think Gunboat Diplomacy is some kind of crapshoot, if you think it’s not a serious game, if you think it doesn’t teach you anything useful for “real” Diplomacy: think again. Experiencing the Gunboat style of gameplay forces you to learn how to think Tactically. If you get good at Gunboat Diplomacy, you will never look at the Classic game the same way again.

There is an infinite number of lessons you might learn from playing Gunboat Diplomacy, so if you find yourself struggling to understand the Tactical layer of Diplomacy, I urge you to play more Gunboat matches. They don’t take up very much time, since all you have to do is decide your moves. I sometimes play three Gunboat games at the same time, and the games take up less than 1 hour of my day.

If you are struggling to understand Gunboat Diplomacy, consider reading a few of my many articles on the subject. And if you haven’t already, read my journal for the Biggest Game of All Time (you will never find a better resource for playing high-level Gunboat Diplomacy).

What about Players Who Say Politics Trumps Tactics?

I am absolutely certain that some other top-level Diplomacy players will have a knee-jerk reaction to disagree with my advice to treat Tactics as more true than Politics. There is a certain kind of mindset that some players have (or at least, will hypocritically sell you) that goes something like this: “If I trust a player, if we are working together, then I’m willing to believe whatever justification they have for their moves, so long as those moves make sense.” Sometimes they’ll take this even further and advocate the attitude that Diplomacy is not really about Tactics at all, and that the game is entirely about “trust.” They won’t just say this in conversations about the game; they say this during matches—and sometimes they even mean it.

I encounter these players myself, of course. Here’s what I think about them:

- Sometimes, I determine that they are sincere. When I do, I will see what kind of dangerous Tactics I can talk this player into…and then massively backstab them. (This is a great way to get off to a strong start, or to get a solo win.)

- More often, the player is greatly over-exaggerating their attitude. Although players commonly claim that Politics is more important than Tactics, there’s a hidden contradiction in this line of thinking. The thoughts have qualifications which cut away at the overall conclusion until there is nothing left. Here’s what I mean: you can only determine whether a player’s explanations “make sense” if you have Tactical acumen. So ultimately it is still Tactics that control your evaluation of the player’s moves and explanations. Thus, it is contradictory or misleading to act like Politics is what matters most.

In your matches, you will encounter players who try to talk you into adopting the attitude that the game is all about “trust” and not really Tactics at all. If you fall for this, you are going to get conned, and often. In my considered opinion, working together with a player necessarily has some Tactical component, so concepts like “trust” have little-to-no meaning without reference to the players’ Tactics.

Listen to me very carefully: the “anything goes” Tactical attitude will get you destroyed. Please, please, PLEASE do not listen to commentators who contradict this warning. In addition to my belief that it is just plain bad advice to overlook the Tactical Layer, I think such commentators are either:

- …valuing something other than winning. There are plenty of players who play Diplomacy to pass the time, and do not try to solo win every match. Some veteran players get bored and take on immense risks just to try something exciting. That’s fine; there’s nothing wrong with playing for fun. But I am skeptical—and I counsel you to be skeptical—of practical advice (“Here’s how to succeed!”) that comes from a perspective that values non-practical goals (“Success isn’t everything.”).

-Or-

- …valuing winning so much that they are trying to maintain a public persona where they pretend not to be ruthless so that they enter Diplomacy matches with an advantageous reputation. Yes, I absolutely believe that there are players who are playing long, long mind games that go beyond particular matches. Read about how Thomas Haver won the 2014 World Championship by cultivating, for years, a reputation as a Care Bear.

Now, you might be thinking, “But BrotherBored, I’ve seen all sorts of crazy stuff happen in Diplomacy matches! There are players who make fake attacks on each other. I’ve seen players completely trust each other from 1901 onward without backstabbing. And there are many situations when allies will have far greater Tactical power (creating mutual gain!) if one shows complete trust in the other. I think you are over-emphasizing the Tactical Layer.”

To that I say: you’re on to something.

The Tactical Layer is where you move your pieces around, tangibly manifest your Political expressions of friendship and hostility, and—in a very literal sense—win the game. Thus, peering through the Political Layer into the objective meaning implied by players’ Tactical choices is an excellent way to develop your lie-detecting skills.

But there is something hollow in insisting that the Tactical layer is what’s “really” happening, even though it looks and feels so real. Something is telling you that the reality you see and experience isn’t what you think it is. You believe me that the player’s words are artificial, but if the Politics isn’t what is animating the pieces to move around the board, what is? What unseen reality is the cause of the events that transpire in the Political and Tactical Layers?

We must peel back the Onion again to discover a deeper layer…

BWUUUUUUUUUUH!!!

>More often, the player is greatly over-exaggerating their attitude. Although players commonly claim that Politics is more important than Tactics, there’s a hidden contradiction in this line of thinking. The thoughts have qualifications which cut away at the overall conclusion until there is nothing left. Here’s what I mean: you can only determine whether a player’s explanations “make sense” if you have Tactical acumen. So ultimately it is still Tactics that control your evaluation of the player’s moves and explanations. Thus, it is contradictory or misleading to act like Politics is what matters most.

There are terms of art us autists like to use. The motte-and-bailey is the more objective one, while the unprincipled exception is a more thorough analysis of the ways that systems of belief work. A motte-and-bailey is when a core argument (the motte) is used whenever the semantic concept comes under attack, meanwhile a more general usage (the bailey) is used when its results are more convenient. This is a fairly naked form of hypocrisy. It can easily be seen through by a determined opponent.

The unprincipled exception is a different sort of analysis. It recognizes that people are self-serving in their beliefs, and successful belief structures accommodate their natural impulses. Moreover, these exceptions are pretty much necessary in order for beliefs to map to real events. Naturally, these exceptions are determined by whoever has “power,” which can be as simple as whoever has the ability to take an effective action. It’s about as nihilistic of a view as the motte-and-bailey, but it’s a more fighting sense of nihilism. It holds up to accusations of hypocrisy where the motte-and-bailey would fail, for the simple reason of pragmatic necessity. Even in mathematical terms, it’s almost impossible to come up with a set of rules that covers every possible circumstance, and even if that were possible no one would go along with a system like that.