On the BrotherBored Patreon, fans submit ideas for articles and help me choose which topic I’ll write about next!

The most recent winning topic was:

Write a Diplomacy article explaining [Your Bored Brother’s] strategic theory that Italy should spread units around the map early on, and that Italy especially depends on having a Raider during endgame.

Introduction

The topic from this month’s drawing came up during a conversation with one of my students. I said that I try to play Italy differently from the other 6 powers, and my student asked me to elaborate. Is there really a categorically different strategy that is especially matched to Italy? I think there is, and in this article I’ll tell you about that strategy and why I think it suits Italy.

Many beginners at Diplomacy consider Italy to be one of the worst powers (if not the worst power). They’ll say something like, “Playing Italy is so boring! You can’t do anything; you just stand around at four supply centers and wait around to die or draw.” Or maybe, “Italy has no choice but to attack Austria, and even that can backfire.”

However, experienced Diplomacy players often say that they enjoy playing Italy, and some even think that Italy is one of the stronger powers. What do experienced Diplomacy players know about Italy that beginners don’t?

Continue forth, dear reader!

Adventure awaits you!

I believe that Italy—perhaps uniquely—can afford to send away at least one unit on an adventure early in the match. I’ll call this unit an “Adventurer” because I am not aware of any existing Diplomacy jargon term for this concept. I think using an Adventurer opens up many diplomatic and strategic options for Italy, expanding Italy’s direct influence far across the map. This heightened influence enables Italy to reach its full potential as a great power. The experts’ use of this technique may explain why novices and experts assess Italy differently.

And during endgame, that Adventurer can become a “Raider” (an existing Diplomacy jargon term referring to a unit fighting behind the opponent’s line), permitting Italy to convert strong positions into actual solo wins.

If you can learn to play Italy the adventurous way, perhaps you will enjoy playing as Italy—and win—much more!

Why can Italy afford an Adventurer?

1. Italy can put up a strong defense in the early game with few units.

Italy’s neighbors face severe logistical problems and risks in immediately invading Italy.[1]France is somewhat distant from Italy, and would risk devastating attacks by England and/or Germany by sending an invasion force against Italy early on. Turkey is even more distant than France, can barely interact with Italy in 1901, and must telegraph any invasion plan well in advance. Most … Continue reading Thus, in most matches, Italy’s neighbors pragmatically choose early-game goals that do not include all-out invading Italy.[2]There are matches where Italy is attacked early. And Italy, like any power, will crumble if attacked by multiple persistent neighbors. I am not claiming Italy is never immediately invaded.

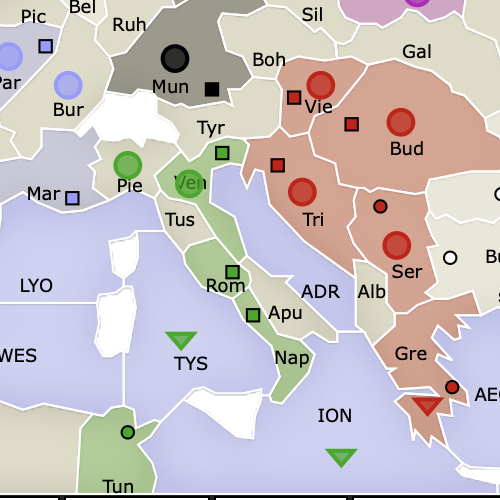

Not only are Italy’s neighbors incentivized to prioritize other early game goals over invading Italy, but also they are dis-incentivized from attacking Italy early due to Italy’s strong defensive capabilities. During the early game, Italy can almost trivially block a naval attack from France or Turkey (so long as Italy took the free capture at Tunis and built a second fleet to supplement the starting fleet). Italy can also build a wall against overland attacks by parking armies at Piedmont and Venice. Consider this map excerpt:

This is a strong defensive stance for Italy. None of Italy’s neighbors can get away with a surprise attack, and none can successfully invade Italy without help from another power.

Italy’s mere theoretical ability to quickly create a defensive position like the one shown here is often enough to deter all but the most determined (and alliance-driven) invasion.

Sure, during the middle or endgame, a 4-center Italy faces diminished defensive prospects. At a mere 4 centers, Italy cannot hold out against a two-front war, and cannot unilaterally defend against a very large foe (who can probably outflank a 4-center Italy). But in the early game, a two-front war is unlikely and no big foes exist.

2. Italy has a great position for sending forth Adventurers.

A great route—perhaps the best route—for sending an Adventurer is through the “no-man’s-land” area of the map. You might call this “an Alpine Adventure!”

In the early game, few players will send units into No Man’s Land, so that area will be relatively uncrowded—or even empty! And so long as Italy isn’t facing the unusual situation of an early-game attack, Italy can afford to send an army sitting in Piedmont or Venice into Tyrolia, then up through Bohemia and beyond.

Another option is to pass a fleet through Mid-Atlantic Ocean. Comparatively speaking, this is much more difficult, as Mid-Atlantic Ocean is often occupied by a French (or sometimes English) fleet. Italy needs a successful guess or support from another player to get through. Although a challenge for Italy, getting a fleet through Mid-Atlantic Ocean during the early game is nigh-impossible for the other Southern powers (Austria, Turkey, and Russia); this is an opportunity unique to Italy.

3. Italy can afford to “waste” a unit.

If Italy is confident that Austria will not attack, then Italy can afford to send one army into No Man’s Land. The remaining army can put up a reasonable defense at Piedmont/Venice. If Italy is confident that Turkey will not attack, then Italy can afford to send one fleet through Mid-Atlantic Ocean. The remaining fleet can guard the seas, and the remaining armies can still put up a reasonable defense.

But just as important—and this is crucial to understanding the flexibility and strength of this strategy—Italy only needs to capture one supply center to fully replenish the starting 4-unit defense force.

For example, if Italy has sent an army into Silesia but feels a need for a replacement army build at Venice, Italy might capture Munich, Berlin, or Warsaw (either by surprise attack or with someone’s support!) and then build an army at Venice. The new army at Venice—added to Italy’s starting army that stayed behind—restores Italy’s defensive capabilities to the same tactical level they were at before the Adventurer left!

For another example, let’s say Italy has a fleet in North Atlantic Ocean. Italy could make a surprise attack on Liverpool, or get another power’s support into Liverpool. With that capture, Italy can in effect “rebuild” the starting fleet (now in Liverpool) back at Naples. Again, this would restore Italy’s defensive capabilities to the starting level.

If the situation becomes really dire—let’s say Italy needs to play a very defensive game and has lost control of one of these distant centers seized by an Adventurer—then Italy can disband the Adventurer and play out the remainder of the match without it.

Why is an Adventurer so beneficial to Italy’s diplomatic strategy?

There are two major strategic reasons why Italy’s diplomacy benefits from an Adventurer. The first is that an Adventurer maximizes Italy’s ability to influence other players. This influence is critical during early and mid-game, as it changes Italy from a passive power waiting for opportunities into an un-ignorable diplomatic actor! The second reason is that, during endgame, the Adventurer can become a Raider—and this Raider can make the difference between Italy getting a strong draw and Italy getting a solo win.

To properly convey just how fitting it is for Italy to use a strategy based on adventure and influence, let me contrast the “Adventure Strategy” with one I consider to be inferior for Italy: what I call the “Spear Toss Strategy.”

What is the “Spear Toss Strategy?”

Most of the Diplomacy powers can succeed by concentrating as many units as possible in one direction in order to conquer one foe after the other. This is what I call a “Spear Toss Strategy.” A large number of units are massed in one place (as the tip of the spear) which then move forward, leaving a sparsely-defended conquered space behind (the shaft of the spear).

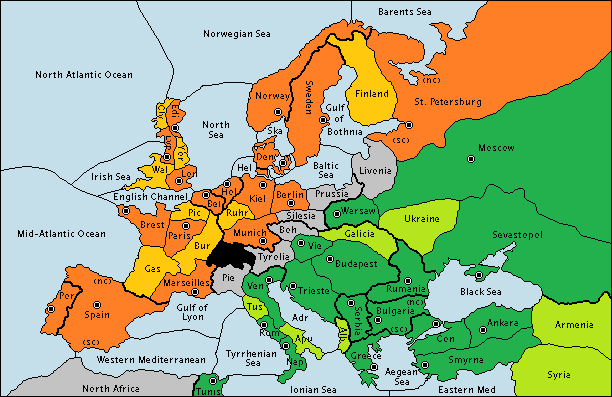

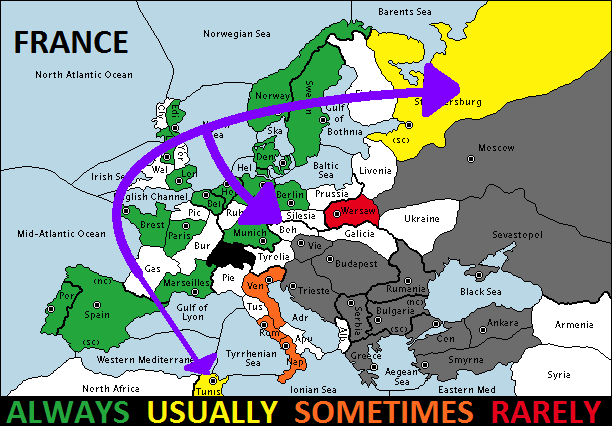

The clearest (and most common) examples I can think of for this Spear Toss Strategy are when France focuses on conquering England and then afterwards sends that mass of units east and south to conquer the rest of the North, or when Turkey masses units westward to play out a Juggernaut alliance.[3]”Juggernaut” is a Diplomacy jargon term for a Russia/Turkey alliance. Every power is capable of employing the Spear Toss Strategy—including Italy! But the Spear Toss is not the only sensible strategy for Diplomacy.[4]I have written before about the Spear Toss Strategy (and why Russia must pursue an alternative) in A Winning Strategy for Russia in Gunboat Diplomacy.

Russia rarely wins by concentrating forces in a single area.

But the Spear Toss Strategy is bread and butter for France!

Italy is worse at the Spear Toss Strategy

Novice players often equate all Diplomacy strategy with variations of the Spear Toss Strategy, and—in my professional opinion[5]Players have actually paid me to tutor them at Diplomacy. It’s not a lot, but I think I can say that I am as professional as a Diplomacy player can possibly be.—this is typically why they misunderstand and underrate Italy. The Italian versions of the Spear Toss strategy—compared to other powers’ versions—are more likely to result in Italy getting destroyed and less likely to result in a solo win (in comparison with other powers). Because novices only understand Spear Toss Strategies, their limited thinking causes them to interpret Italy as a power with few options. Because novices only attempt Spear Toss Strategies, their poor results from attempting this as Italy cause them to think Italy is weak.

Italy can pull off two versions of the Spear Toss Strategy: send everything against Austria, or send everything against France. These strategies can work, but either way, the Spear Toss Strategy is less likely to work out for Italy because Italy is a central power, and thus must leave a “backdoor” completely exposed to invaders (traitorous or otherwise) for many years in order to concentrate forces in one direction.[6]France and Turkey, corner powers, don’t suffer from this problem to the same extent.

If you’re a novice player reading this article, I can guess at what you’re thinking: “But if Italy is worse at attacking neighbors, doesn’t that just make Italy worse?” And to that I say: it’s certainly a disadvantage. But Diplomacy is in fact a well-balanced game; Italy has other, different advantages to make up for this weakness. Learning to play Italy well means considering alternative strategies to the Spear Toss Strategy, and learning to identify the right situation for tossing a spear versus the right situation for trying an alternative…[7]I’m not saying “Italy should never use the Spear Toss Strategy.” I’m saying, the Spear Toss is not Italy’s best strategy and I advise you to use it less often than “always.”

Italy is actually a diplomatic powerhouse

Concentrating forces in one direction sacrifices what I consider to be Italy’s best advantage: the power of diplomacy. Instead of concentrating forces, Italy can choose to spread units around the board, and these spread-out units can influence everything in the match.

In my article about my preliminary and semi-final matches in the ODC 2019, I complimented myself for a well-played match as Italy:

Unlike England and France (corner powers), Italy is a central power. As such, Italy has different strategic opportunities and limitations. As Italy, I sent my units allllll over the map in different directions, trying to accomplish cryptic strategic goals and pick up little favors here and there. This is why the final board shows me with the strange configuration of having captured all 3 Turkish home centers and all 3 German home centers.

2019 Online Diplomacy Championship Finals

I am proud of my result from this match. Although the quality of my play is not necessarily reflected in a high score (35 is good, but not enough to qualify by itself for the finals), I am experienced enough to recognize that I played a strong game as Italy. To paraphrase what one of the players said to me during the match, I was a “muscular, globe-trotting” power that managed to involve itself in every single conflict on the board with a mere 5 pieces.

Italy’s strength lies not in tactics (like a corner power), but rather in Italy’s ability to influence distant rivals with more than just words. When played by an expert diplomat, Italy has the potential be the most powerful of all seven great powers. When played this way, Italy can help or hinder almost any rival. Italy can accrue favors from all over the board. Italy will have a say in almost everything that transpires in the match. If you can learn to understand Italy the way that I understand Italy, you might come to think of Italy as synonymous with diplomacy itself.

One army patrolling up and down No Man’s Land can harass (or help) France, Germany, Austria and/or Russia. One fleet messing around in the Atlantic can force every northern power to negotiate with you every turn. Yes, one piece can’t invade and destroy a rival. But it is precisely because an Adventurer yields little information about your strategic aims that it is so powerful! The Adventurer doesn’t inherently support any particular strategic aim, and what it is doing can (and should) vary from turn to turn. That one unit could change the trajectory of many conflicts—and if you so desire, change it back again!

Realizing this, your distant rivals will be sucked into negotiating with you in a detailed way because the Adventurer matters to them tactically in a way your other, far-away pieces do not.

I cannot overstate the importance of getting involved in everyone’s decisions. Independent of what you decide to do for your moves, you decide who to tell (or not tell) the information you learned. If you communicate well, you might know where every piece on the board will move ahead of time. If you communicate masterfully, you might have a say in where every piece on the board will move! When everyone is talking to you—really talking to you, because they desperately want a say in what your Adventurer does—you are the boss; you are the mafia don; you are the puppet master.

To the same degree that Italy is not that great at the forceful Spear Toss Strategy, Italy excels at the diplomatic Adventure Strategy. Italy can accrue small advantages and use influence to create an advantageous strategic situation or even a winning situation.

How does the Adventure Strategy help Italy win though?

Adventuring helps Italy get closer to winning throughout the match! But during endgame, an Adventurer unit can take on a critical tactical role: the role of Raider.

What does a “Raider” do in Diplomacy?

“Raider” is a Diplomacy jargon term referring to a unit that is behind an opponent’s defensive line. This could happen because a unit travelled behind that line before the rivals were hostile or because the unit cleverly slipped through a gap in the defenses.[8]A great way to get a Raider in the middle of a fight is with a “forward retreat.” The rulebook doesn’t require retreating units to literally move backwards, so you can opt to send a dislodged unit even further away from your starting position if your enemy left such a retreat … Continue reading

The reason why this unit is called a “Raider” is that a lone unit has the ability to interfere with the other players’ moves and orders… but doesn’t really have the ability to conquer and hold any consolidated position.

Most Diplomacy players are reluctant to use a unit as a Raider early in the match because Diplomacy’s rules (especially the ability to issue support orders) generally favor a player concentrating their forces. However, during endgame, when one player is attempting a solo win, a Raider has tremendous tactical value for players on both the offense and the defense.

During endgame, previously-spread-out units will concentrate into the small regions of the map in which vital struggles are taking place. Units on the periphery of these concentrated struggles will be unable to do much of anything (as they will be impeded by the units standing in their way). Players defending against a solo win attempt can create a stalemate line (or otherwise defensible position) that nullifies the possibility of a solo win by blocking the aggressing player’s units from reaching more supply centers.

But if the player attempting a solo win has a Raider that is already behind the defenders’ line…the defenders are in trouble. The defenders may not be able to cover enough supply centers to prevent a solo win, or they may not be able to form a true stalemate line because the Raider can cut their support orders from behind.

A defensive Raider can be strong as well, as the player trying to solo win would like to concentrate their fire power on the places they want to conquer—and might be unable to do so because of how many units it will take to block or surround the Raider.[9]A problem I struggled with during the endgame of “Media Wars,” as a lone enemy fleet demanded the attention of at least four of my own units just to contain it.

Effortlessly, an Adventurer changes into a Raider…

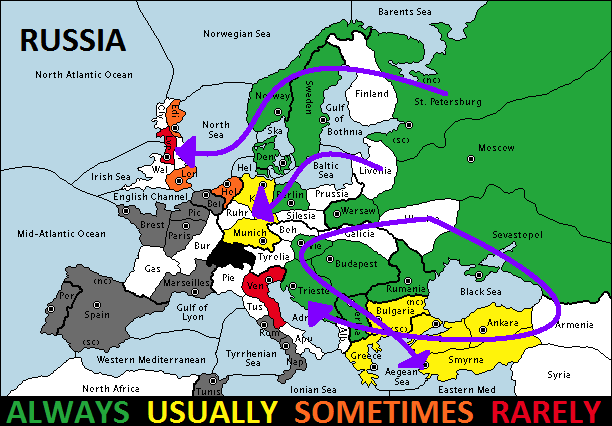

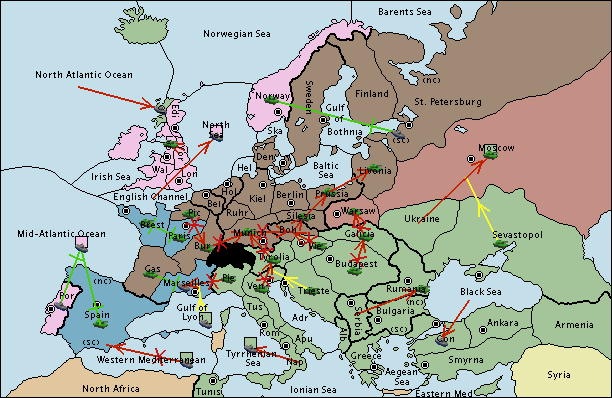

Check out this screen cap of a match I won as Italy:

If you are familiar with stalemate lines, you might be thinking “Oh, these other players should have been able to stalemate Italy here…I guess BrotherBored won because the other players blundered and failed to form the stalemate line.”

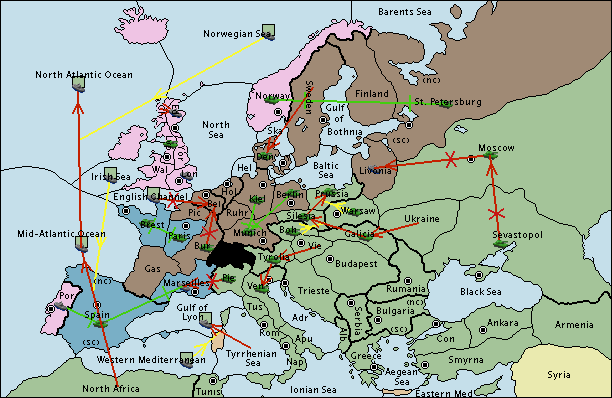

Let’s look again at the board, this time without the crop:

Now, looking at this board, an astute player will observe that my solo win was probably inevitable at this point. The defenders lacked sufficient fleet power in the North to stop me.

Three years later, the board looked like this:

The presence of just one Italian fleet behind the Mid-Atlantic Ocean position collapsed the defenders’ line.

This match is a plain example of how a Raider can be difference between a draw and a solo win.[10]Edit: A curious reader asked me for a hyperlink to the match on webDiplomacy. In case you too are wondering, the match was actually a Gunboat game I played in a private league! (My league lasted about 3 years.) I believe the Adventure Strategy I’ve outlined here is workable in Gunboat … Continue reading

Obviously, any power can benefit from a Raider, so why is Your Bored Brother emphasizing Raiders so much in this article about Italy? What makes the Raider so important to Italy?

Italy needs a Raider more than other powers

When it comes to playing for a draw, Italy has an advantage. As I outlined in 5 Reason I Love to Play as Italy in Gunboat Diplomacy, Italy straddles the area of the map that is tactically critical to stalemate line formation on either side of the typical lines: the region stretching from Portugal to the coasts of Tyrrhenian Sea. This means even a modest Italy often decides if or how the match ends in a draw.[11]As aptly demonstrated by the end of “Media Wars”, where a 1-center Italian player decided how the match ended for precisely this reason.

But this position also puts Italy at a disadvantage when it comes to playing for a solo win.

If Italy has expanded east and attained a strong position, western powers can foresee Italy’s solo win attempt and (rather easily) block Italy’s westward expansion behind a stalemate line. Venice is 2 moves away from taking Marseilles, and all of Italy’s home centers are 3 moves from Spain and 4 moves from Portugal, meaning Italy is several years away from conquering those positions with newly-built units.

And if Italy has taken Iberia early and is later massing power to conquer the East, the defenders can also see this coming and lock up Warsaw, Moscow, and even Sevastopol behind a stalemate line. The logistics of Italy transporting armies to the distant east (Galicia/Ukraine/Rumania/Armenia) are tremendously challenging, so Italy’s late-game builds will not make a difference in that fight.

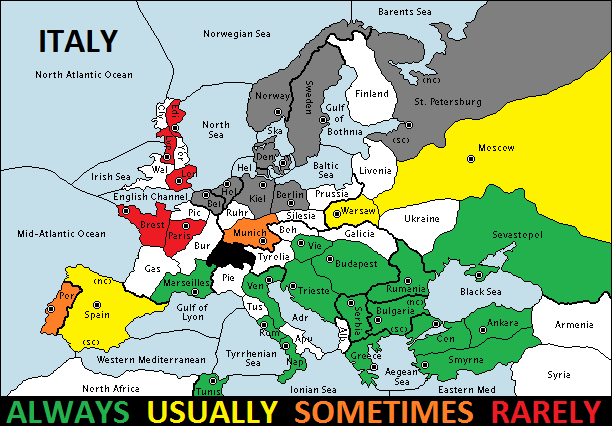

I created this map as a beginner’s guide to Gunboat Diplomacy, but I think it is worth viewing during this discussion:

The other two central powers (Germany and Austria) and Russia[12]I, Your Bored Brother, increasingly think of Russia as an honorary central power instead of a corner power, since I see more similarities in tactical and diplomatic dynamics between Russia and the so-called central powers (Germany, Austria, Italy) than Russia and the other so-called corner powers … Continue reading differ from Italy in that new armies built by Germany, Austria, or Russia late in the game are immediately useful in fighting over key endgame positions.

So, although a Raider is beneficial to any power striving for a solo win, I say that Italy needs a Raider more than other powers because Italy is at a disadvantage in making an endgame push with newly-built units. And although the corner powers England, France, and Turkey would benefit as much as Italy from a Raider, those powers’ positions rarely afford them an opportunity to create one deliberately (and in any event they have different advantages). Thus, if I were to ask “If there is one power who can and should create a Raider more often than the others, which power is that?” I would answer “Italy.”

Conclusion

The adventurous Italian strategy I have outlined in this article is probably not for beginners, and it is definitely not for lazy players. The Adventure Strategy is not for beginners because in order to maximize the value of influence, you must understand how to influence other players and what it is in your interest to influence them to do. And the Adventure Strategy is not for lazy players because succeeding requires you to work your @$$ off, as the strategy inherently relies on communicating with every player (in great depth!) each turn.

But if you feel up to these challenges—if you have some diplomatic insight and you are ready to work hard to win—then learning this strategy could change Italy into your favorite Diplomacy power. I know Italy became my favorite after I learned to play Italy this way!

What do you think? Is my strategic advice for Italy wisdom…or folly? I’d love to hear from you in the comments below!

I love creating content for you, dear Reader. Truly—there’s no way I’d be doing this if I didn’t enjoy it. You can show me some love too by becoming my Patron on Patreon. I promise I feel ecstatic every time I get a new Patron. I’m not asking much; why not give it a try!

Footnotes

| ↑1 | France is somewhat distant from Italy, and would risk devastating attacks by England and/or Germany by sending an invasion force against Italy early on. Turkey is even more distant than France, can barely interact with Italy in 1901, and must telegraph any invasion plan well in advance. Most Austrian players are reluctant to attack Italy immediately, because doing so leaves Austria too vulnerable to attacks by Russia and Turkey. And finally, a German invasion of Italy in the early game is so impractical and counter-productive that I’d call it “silly.” |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | There are matches where Italy is attacked early. And Italy, like any power, will crumble if attacked by multiple persistent neighbors. I am not claiming Italy is never immediately invaded. |

| ↑3 | ”Juggernaut” is a Diplomacy jargon term for a Russia/Turkey alliance. |

| ↑4 | I have written before about the Spear Toss Strategy (and why Russia must pursue an alternative) in A Winning Strategy for Russia in Gunboat Diplomacy. |

| ↑5 | Players have actually paid me to tutor them at Diplomacy. It’s not a lot, but I think I can say that I am as professional as a Diplomacy player can possibly be. |

| ↑6 | France and Turkey, corner powers, don’t suffer from this problem to the same extent. |

| ↑7 | I’m not saying “Italy should never use the Spear Toss Strategy.” I’m saying, the Spear Toss is not Italy’s best strategy and I advise you to use it less often than “always.” |

| ↑8 | A great way to get a Raider in the middle of a fight is with a “forward retreat.” The rulebook doesn’t require retreating units to literally move backwards, so you can opt to send a dislodged unit even further away from your starting position if your enemy left such a retreat option open to you. |

| ↑9 | A problem I struggled with during the endgame of “Media Wars,” as a lone enemy fleet demanded the attention of at least four of my own units just to contain it. |

| ↑10 | Edit: A curious reader asked me for a hyperlink to the match on webDiplomacy. In case you too are wondering, the match was actually a Gunboat game I played in a private league! (My league lasted about 3 years.) I believe the Adventure Strategy I’ve outlined here is workable in Gunboat Diplomacy, but (1) the strategy is not as powerful in Gunboat; and (2) how to influence players diplomatically in Gunboat is too complex a topic to include here. I picked this Gunboat match simply to illustrate how possessing a Raider can be decisive for Italy. |

| ↑11 | As aptly demonstrated by the end of “Media Wars”, where a 1-center Italian player decided how the match ended for precisely this reason. |

| ↑12 | I, Your Bored Brother, increasingly think of Russia as an honorary central power instead of a corner power, since I see more similarities in tactical and diplomatic dynamics between Russia and the so-called central powers (Germany, Austria, Italy) than Russia and the other so-called corner powers (England, France, or Turkey). |

Leaving aside whether your advice is good or bad (for the moment), I’ll just point out that the concept you call the “Adventure Strategy” has been written about before. It was called “Scatter Theory”. diplomacy-archive.com has two articles about it.

Aha, I kept thinking to myself “somebody has to have written about this before,” but the folks I consulted couldn’t remember a specific term or point me to an article. I might have used existing jargon if I had known. If you know the hyperlinks to the old articles, would you include them here for the benefit of an interested reader?

The original Scatter Theory article: http://www.diplomacy-archive.com/resources/strategy/articles/scatter.htm

The sequel: http://www.diplomacy-archive.com/resources/strategy/articles/son_of_scatter.htm

Further commentary from the keeper of the diplomacy-archive site: http://www.diplomacy-archive.com/resources/strategy/articles/ambassador.htm

To my unexperienced mind, I think it’s a great strategy! I would think that there is some risk in upsetting/alienating Germany/Austria by moving to Tyrolia early on, requiring extra TLC for them, but that’s why they call it Diplomacy! I would think it’s the kind of thing to do and then ask for forgiveness afterwards (or to make other movements at the same time that show that the intention is not hostile). Or, (if they are savvy players), I would think they would see the benefit for them in having an extra army that they could have access to.

This is a great article, but all the references to negotiation have me wondering if this is more of a press strategy as opposed to a GB strategy? In your “5 Reasons I Love to Play as Italy in Gunboat Diplomacy” article, you don’t mention this idea, so I’m wondering about it’s viability in a GB setting.

Also, you mention sending the adventurer out in the “early game”. Can you be more specific? Is 1903 or even 1904 still the “early game”, or should an adventurer depart for foreign lands before that?

I consider this strategy to be much stronger in Press Diplomacy, since some of the advantages (like negotiating with many players) don’t make sense in a no-press environment. I emphasized the press aspects, and so I categorized this post as a “Press Diplomacy” article.

That said, I do think a version of this strategy is viable in Gunboat Diplomacy. Influencing other players in Gunboat Diplomacy is so subtle, and explaining all that would expand the scope of the article to something much deeper than its nominal topic, haha. I try to be careful not to nest a big concept inside of a small one.

I define the “early game” as that phase of the match when all seven powers are still viable. So for me, the early game is not defined by time, but rather the strategic situation. (I have played matches were no power took significant damage until well past 1905.) The Adventurer works best if you can send the unit out during early game (as I defined it), because the battle lines are fluid and your ability to influence many players is greater (and matters more) during this phase of the match. Once there is a dominant power or solid alliance, there is a lot less for an Adventurer to do.

I think it is reasonable to start adventuring in 1901 (say by opening VEN to TYR, ROM to APU), but it is not critical to start in 1901.