The Charismatic Serial Killer Archetype, Part 5:

The Perverse Fantasy of Heroic Killing

What’s the backstory on this essay…?

I started writing this series of essays about serial killer characters back in October 2018 after I watched the theatrical release of Sony’s superhero movie Venom (2018). I published the first four parts in January and February of 2019…and then I left this project by the wayside.[1]Let’s be real here: my Diplomacy content started taking off in popularity, so I decided to focus on my Diplomacy articles over my philosophy essays. I am aware that this essay series is not even close to as popular as my Diplomacy content, but I don’t care. I consider this essay series … Continue reading

My unfinished draft for the rest of this series languished, unpublished, for over a year—even though I had written the first draft of the entire series in a fugue state in the weeks after I saw Venom!

The other day, I heard that the sequel to the Venom movie has been in production and may be finished soon. (The title? Venom: Let There be Carnage.) I felt silly that the movie producers might be able to finish an entire sequel movie before I could wrap a mere essay series. In particular, I felt embarrassed about myself that the essays have been 80% finished this entire time, and I just never got around to making a final pass.

Well, I’m through neglecting this project. Time to see this series through to its thrilling conclusion!

Previously, on BrotherBored…

In Part 1, “The Epidemic of Serial Killers,” I wrote about how Venom (2018) includes a teaser scene showing the serial killer who becomes the supervillain Carnage. The scene introducing Cletus Kasady presented him in a similar way to how Dr. Hannibal Lecter is depicted in The Silence of the Lambs (1991) and other scenes portraying murderous supervillains. I framed Carnage / Cletus Kasady as part of “The Charismatic Serial Killer Archetype” and stated my thesis that this kind of character is so popular because he is “cool.”

In Part 2, “American Minds & American Movies”, I discussed methods of discovering other people’s hidden thoughts. I said these methods can apply to society-at-large. I said that the art—specifically, the movies—created by American society can help us understand the unspoken assumptions and other hidden ideas within American culture.

In Part 3, “The Meaning of Cool,” I defined what it means to be “cool.” I said that a cool person is someone who transgresses a society-wide social boundary (a custom, rule, law, etc.) in front of a group of people who privately do not believe in the boundary (even though they may typically respect the boundary to avoid consequences). A person becomes “cool” by transgressing a boundary that their friends or audience would like to see transgressed.

In Part 4, “The Killing Taboo is a Sham,” I established why I believe that the taboo against killing is only nominal in U.S. culture—in other words, that many Americans privately or secretly do think that killing people is O.K., even as they acknowledge a culture-wide prohibition on the same. My argument was that all sorts of American cultural artifacts—from our guns, to our police, to our violent and sadistic action heroes—imply a vast hidden approval for lethal violence.

Let’s explore my idea that calling some characters “heroes” and others “serial killers” is a distinction without difference.

Americans are gratified by fantasies of lethal violence, even as they speak with disapproval of killing. Americans love protagonists to be killers, and they love killers to be protagonists. Americans enjoy their killer protagonists to be gratified by the killing, because the audience vicariously experiences the gratification too. Charismatic serial killers are the coolest, because they live out our deepest collective desires.

The Desire to Kill Precedes the Killing—Even for Heroes, Even When Acting in Self-Defense

If you are feeling like you ought to disagree with me, I think you might say something like:

But BrotherBored, the relevant distinction between serial killers and superheroes is that true serial killers hunt their victims down, whereas these other characters are placed into situations where they are compelled to kill for some reason other than psychological gratification.

To this I say: you have ignored the fact that these are fictional stories. The heroes are created so that they can kill, and the story contrives to explain the killing so that the audience feels comfortable.

What did I just say!?

That’s right: the decision by the writer to have these characters kill (or use deadly force) precedes the writer’s’ creation of a situation for the character to do so.

Even if I treated the fictional narrative like a true story, the characters still choose to put themselves in situations where killing is somehow “necessary.” The same can be said of everyday people who “need” to use lethal violence—they often choose a profession or lifestyle that “requires” them to dispense lethal force.

In my opinion, there is no such thing as “necessary” killing under any circumstances. I do think that killing could be the morally appropriate course of action, but that does not mean killing was somehow necessary. I think this phrasing (and the thought that gives rise to the phrasing) is trying to obscure the moral agency of the killer. Nobody is compelled to kill others—or take any particular action at all for that matter![2]For you pedants out there, I am taking issue with using words like “necessary” or “forced” or “compelled” to refer to an action that is in actuality volitional. I acknowledge that a person’s physical actions can lack volition, e.g., a reflex.

In real life, there are plenty of people who would rather die than voluntarily take the life of another person, but movie hero characters are essentially never based on this kind of person. It would be far too difficult to tell the violence-affirming story that the writers want to tell![3]Again, I love you Avatar: The Last Airbender (2005-2008). Even if the movie is based on a true story, the decision to tell a violence-affirming story (over the limitless opportunities to tell other true stories) comes from somewhere: the filmmaker’s desire to make a movie that affirms violence.

In other words, our collective fantasies about killing each other come first, and then someone imagines or remembers a situation where the killing can be justified (so that we can be comfortable with the fantasy). So the distinction made by my mocked-up nay-sayer is as flimsy as the distinction between an alcoholic and a so-called “social drinker” who seeks out every possible social situation that could involve alcohol.

Fantasizing About “Necessary” Killing

Many Americans have a suppressed desire to kill that can only be permissibly expressed in the context of protecting others. For example, I have personally heard several young men—and I think even this small number is telling, because honestly I don’t know very many young people—voice fantasies about being present during a mass shooting so that they can personally kill the shooter. A mass-shooter or a serial killer “deserves” death, so he is imagined into existence so that there exists someone acceptable to kill.

My impression is that taking down a mass shooter is a somewhat common fantasy of young men in America. Not only have my friends and family reported similar anecdotes, but this exact idea was evidently common enough to be portrayed in a scene in the recent teen comedy 8th Grade (2018) (wherein the potential love interest teen boy explains how he would personally destroy any would-be mass shooter at the school; the imbecility of his attitude is played for a laugh).

Ignoring whether it is healthy to fantasize about being present during a horrific crime like a killing spree, why is the fantasy about killing the shooter with one’s own weapons? What I mean is, maybe it is okay to imagine the ways in which one could be a hero—and of course a hero is most needed in a grim situation. But why not fantasize about any other heroic way of overcoming the threat?

It’s because the fantasy is about. killing. the. villain. The fantasy is not complete if the villain is merely subdued, or talked out of it, or scared away. In my opinion, this fantasy is clearly about the psychological gratification that comes from killing the villain.

Heroes Don’t Have to Kill People

In my mind, a hero is someone who takes great personal risk to help others in a way that most people can’t or won’t. Wouldn’t the fantasy of heroism be more perfect if the hero were to simply deter a spree shooter with the power of words, since that requires greater bravery and more uncommon talent than shooting him dead?[4]One of my favorite shows, Steven Universe (2013-2019), deals with this idea in many episodes. That is a big factor in why I love the show so much.

If you find yourself thinking “BrotherBored, that’s ridiculous, even for a superhero fantasy,” think again. Antoinette Tuff, a black woman who lives near me, achieved this level of heroism in reality! There are countless other examples, all over the world, of would-be criminals who are deterred with the power of words instead of violence. With this in mind, I find it easy to claim that the apparently-common fantasy of “taking out” a mass-shooter supports my conclusion that the desire to inflict deadly violence precedes the imagination of a situation where violence might be called for.

An Excuse for an Action is not the Cause of the Action

Let’s imagine the example of an adult who enjoys giving gifts to other people, especially children. Showering gifts on children, especially when there is no occasion to do so, can be a social faux pas; such gift-giving may be perceived as spoiling the children or trying to acquire some kind of favor. And especially if the potential recipient of gifts is another adult, or children who are not close family, un-occasioned gifts will probably be seen as creepy. A wise gift-giving person probably won’t give gifts until there is a socially-appropriate occasion to do so (like a birthday, holiday, or a special visit). But the occasions are not the cause of the gift-giving if the desire to give gifts is simply suppressed until it is socially appropriate to express. Do you get what I’m saying?

Our hypothetical gift-loving adult is distinguishable from the usual rabble who give gifts to other people on holidays and birthdays out of a sense of obligation. These two kinds of people may appear very similar (since they both give gifts on occasion), but within their subjective experience they are very different.[5]Although I might think that the person who loves giving gifts would probably give gifts more often and more thoughtfully. Of note, the latter kind of person probably never expresses any thoughts or opinions about how great it is to give gifts on holidays; indeed, you might even get them to admit that they only do it out of social obligation.

In the same way, people who like killing (or at least, like to express that they like killing) have to confine their behavior to a range of situations in which killing is considered socially acceptable. For such people, these situations are merely excuses to inflict violence and not the cause of it.

Look for Trouble and You Will Find It

I think many people intuit what I am saying here, even if they aren’t quite able to articulate what they think. Wary people are often concerned about those who deliberately put themselves in situations where violence is likely to become “necessary.” This conventional wisdom is expressed in the rhetorical question asked by any American averse to police: “Why do you want to be a cop?”

Appropriate motivations for becoming a police officer (or other law enforcement or military roles) include wanting to protect those who are unable to protect themselves, a sense of duty towards a beloved community, or even just wanting a job with good pay and early retirement. But some people seek the role because they want to be trained with firearms and be authorized to use force on other human beings.[6]I suspect that the greater the percentage of law enforcement personnel that one perceives to have an improper motive, the more anxiety or antipathy one will have towards the profession.

When someone has the desire to lawfully inflict violence on other people, that person can find or create some situation in which it is appropriate to do so. If you drive around with loaded guns, patrolling as a member of a neighborhood watch, you’ve got a far higher chance of fatally shooting someone “in self defense” than a person like me who doesn’t own guns and doesn’t drive around looking for people to shoot. In other words, even if George Zimmerman deserves his exoneration due to his claim of self-defense, he still intentionally created a situation where he would be able to legally shoot someone and took every action to maximize his chances of being able to do so.[7]Sorry if you are unfamiliar with this murder trial. This trial is one of the most famous murder trials in recent U.S. history and I used to go to school not too far from the crime scene, so this example really pops into my mind. Someone like me will never find himself shooting another person in “self defense” because I don’t own a gun and don’t patrol for “suspicious activity.”

Is This a Movie or is This Reality?

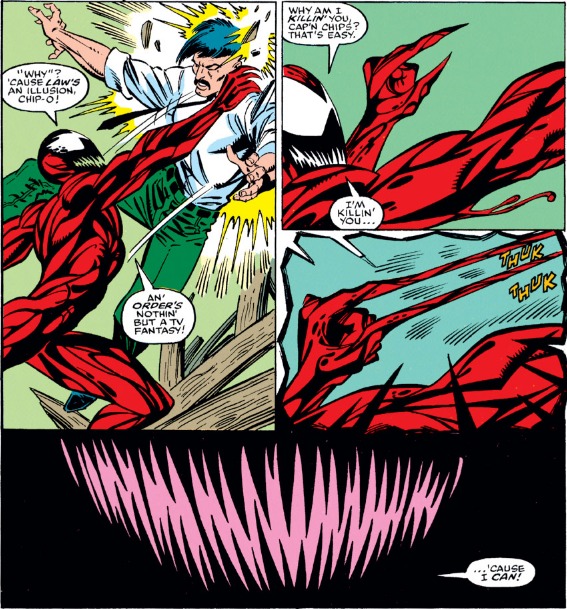

Comic Book Carnage is here to tell us that this isn’t a movie:

Cletus Kasady told Eddie Brock “All ya need is will!” but maybe he should have said “and access to firearms.”

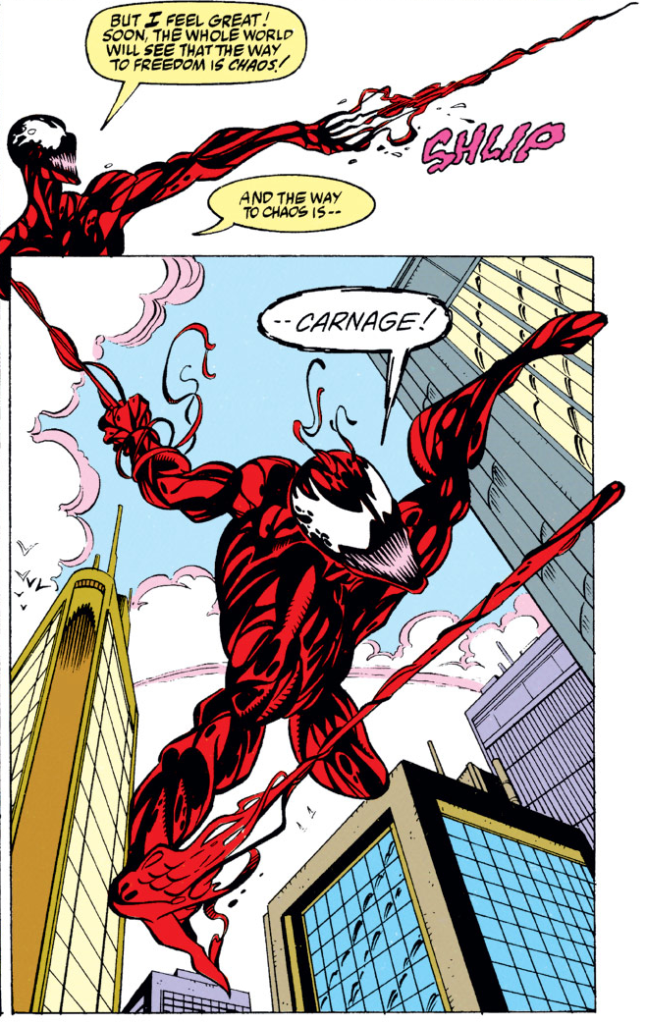

Carnage is here to tell us “This is reality!“

Why is the Charismatic Serial Killer so Cool?

Carnage is our representative today. After all, this character inspired my writing.

The Charismatic Serial Killer knows that, quote, “law is an illusion” and “order’s nothing but a TV fantasy.”

That wraps up Part 5. In Part 6, I will talk about how all of us (as citizens and audience members) participate in our culture of violence, and explore further why the audience and the writers are enthralled by the Charismatic Serial Killer (instead of being repulsed).

Meanwhile, to my fellow Americans: Happy Independence Day!

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Let’s be real here: my Diplomacy content started taking off in popularity, so I decided to focus on my Diplomacy articles over my philosophy essays. I am aware that this essay series is not even close to as popular as my Diplomacy content, but I don’t care. I consider this essay series a labor of love! |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | For you pedants out there, I am taking issue with using words like “necessary” or “forced” or “compelled” to refer to an action that is in actuality volitional. I acknowledge that a person’s physical actions can lack volition, e.g., a reflex. |

| ↑3 | Again, I love you Avatar: The Last Airbender (2005-2008). |

| ↑4 | One of my favorite shows, Steven Universe (2013-2019), deals with this idea in many episodes. That is a big factor in why I love the show so much. |

| ↑5 | Although I might think that the person who loves giving gifts would probably give gifts more often and more thoughtfully. |

| ↑6 | I suspect that the greater the percentage of law enforcement personnel that one perceives to have an improper motive, the more anxiety or antipathy one will have towards the profession. |

| ↑7 | Sorry if you are unfamiliar with this murder trial. This trial is one of the most famous murder trials in recent U.S. history and I used to go to school not too far from the crime scene, so this example really pops into my mind. |

I wish there was a Part 6.